Here’s How Determining The Cost Of Borrowing Might Be Done In A Post-Libor Era

Three major banks have already shelled out nearly $2.6 billion in penalties related to fixing the key London interbank lending rate, known as Libor, and calls to scrap the system altogether have been getting louder ever since the Libor rate-fixing scandal erupted last summer.

As far back as 2008 there have been suspicions that bankers had been manipulating the benchmark interest rate upon which virtually every type of borrowing cost is based worldwide, and now it seems like the global financial system might be taking concrete steps to radically change the fundamental way to determine your credit card APR, your mortgage lending, your auto financing and other ubiquitous forms of borrowing totaling more than $40 trillion in global transactions every day. Regulators believe some banks collaborated to fix the rate.

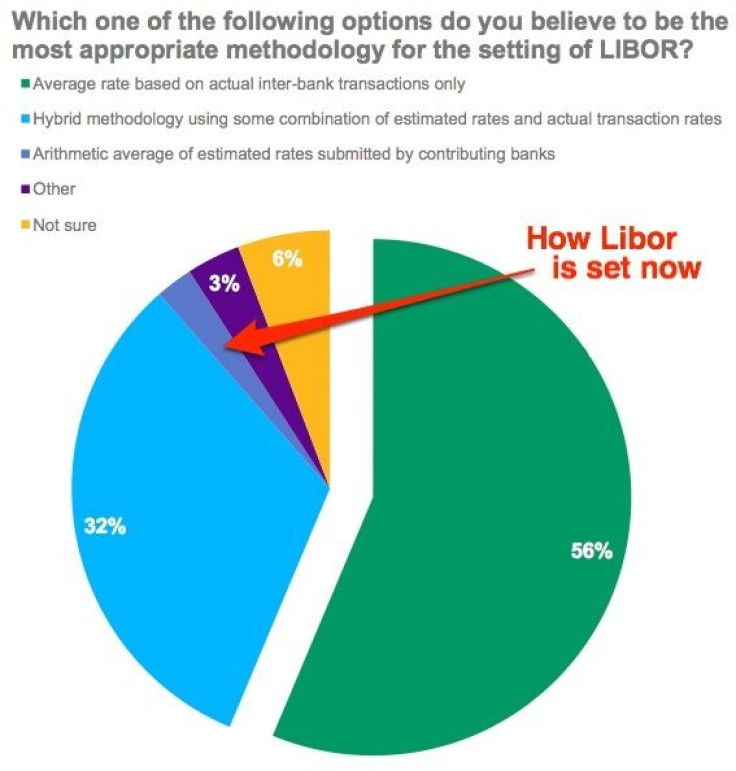

The way this benchmark rate is determined may be on its way to getting replaced by a so-called “dual track system,” according to an exclusive report in The Financial Times published Sunday, citing the top U.K. regulator in charge of Libor reform. The U.K. is looking to replace the Libor with a system based on a hybrid of two data sets: a daily survey of lending rates similar to the current one along with actual day-to-day transaction data. This hybrid approach offers the appeal of being less prone to manipulation.

British regulators believe this system of combining the survey-based system with the real numbers from the day before would remove the “just trust us” aspect of determining the daily interbank lending rate. Currently -- though under greater scrutiny -- a small group of bankers behind closed doors come up with their estimates on how much they charge each other to loan money, often on an overnight basis. These submissions went to the British Bankers’ Association, usually late every workday morning, until last September when U.K. regulators took over the job as they try to identify a fix to the problem.

But the head of the new British Financial Conduct Authority told the Financial Times that whatever fix is made has to be approved by the banks themselves: “If you change the definition, it’s almost certain that one side of every one of those trades would lose out and then would say: 'We’re no longer bound by this.’”

After the Libor scandal went ballistic last June -- when Barclays PLC (LON:BARC) was ordered to pay $200 million by the U.S. Commodity and Futures Trading Commission -- one of a series of penalties leveled at Barclays, UBS AG (NYSE:UBS) and Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc (NYSE:RBS), other banks started looking for alternatives to determining this important interest rate.

The Libor rate has been the benchmark since the 1980s and solidifying a replacement could take years. The dual-track system could run afoul of U.S. regulators who are calling for a system based solely on actual transaction numbers rather than what banks estimate they will charge each other for the coming day. One index that banks have been eyeing is the GCF Repo Index, which has been published by New York-based Depository Trust & Clearing Corp. since 2010. It tracks the repo rate, an important metric for determining the cost of short-term funding for banks.

Repos, which are repurchasing agreements, are made between the seller and the buyer who agree to transact government bonds typically on an overnight basis. (To view the GCF Repo Index, check out the Wall Street Journal’s daily money rates table.)

The repo rate is not based on what bankers estimate their daily costs to be but is instead based on the actual transitions that took place the night before.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.