The High Cost Of Healthcare: America's $15B Program To Pay Hospitals For Medical Resident Training Is Deeply Flawed

SEATTLE -- A few years ago, a 30-year-old pregnant woman came into the emergency room at Stanford University Medical Center in California. She realized she was spotting while out to lunch with her mother, and panicked. She had struggled to become pregnant for five years and it was just 10 weeks into her first term.

Dr. Keith Chan remembers being called to her bedside to perform an ultrasound. At that time, 37-year-old Chan was only a medical student at Stanford, but he already knew enough to diagnose and comfort the worried mother-to-be.

“I remember telling her, ‘Your baby is fine -- here's the heartbeat. I think things are going to be okay,’” he says.

Now, Chan is entering his fifth year of residency in diagnostic radiology at the University of Washington School of Medicine. By this point, his daily duties look very similar to those of a practicing radiologist. But the hospital he serves pays him less than a fifth of what it would have to pay a radiologist to perform the same work.

In fact, the nation's teaching hospitals have argued for years that residents such as Chan actually represent a net drain on their resources, and press the federal government to reimburse them for the money they say they loose by letting Chan practice his skills within their walls. That argument has persuaded the government to pay hospitals more than $15 billion a year to cover the annual salaries and training of 115,000 medical residents such as Chan for decades.

Meanwhile, America's medical residents diagnose and treat patients, perform surgeries and counsel families at a fraction of the cost of a practicing physician or surgeon. Over the past few years, Chan worked as the only radiologist on duty during the night shift in the X-ray laboratories at the University of Washington Medical Center and Harborview Medical Center. Faculty would check his work the next morning, long after he had sent some patients to surgery.

“We start taking calls the second years of radiology,” he says. “At that point, you're already the one diagnosing strokes in the middle of the night.”

The government's generous payments are based on a longstanding assumption: that America needs doctors, and the nation’s 1,203 teaching hospitals must be paid to train the next generation of physicians. But it’s not clear how much it actually costs to support a resident, or how hospitals spend these payments.

Critics say this opacity prevents anyone from finding out whether the funding is necessary, or whether it could instead be put toward furthering other healthcare goals such as encouraging more primary care physicians, or boosting medical access in rural areas.

“It's essentially a hospital subsidy cloaked as an educational expense,” said Dr. Fitzhugh Mullan, a pediatrician and health policy expert at George Washington University.

Last year, Mullan served on a committee of health economists, policy leaders, physicians and medical school deans convened by the Institute of Medicine that called for more transparency and other reforms to the program known as Graduate Medical Education (GME) which funds medical residents at hospitals across the country. They said without these measures, taxpayers may never know whether the billions of dollars that hospitals receive each year are spent in the nation’s best interests.

“It's not tied to anything. It just comes as a lump sum to the teaching hospitals, and the head of the teaching hospital distributes it however they want,” said Tom Ricketts, a retired health policy expert at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “It's really just pretty much unaccountable money.”

But the group’s request for greater transparency and other changes were fiercely opposed by the American Hospital Association, the American Association of Medical Colleges and the American Medical Association. A new residency year began in July -- a year after their report was issued -- and those reforms still only exist on paper.

An Addictive Legacy

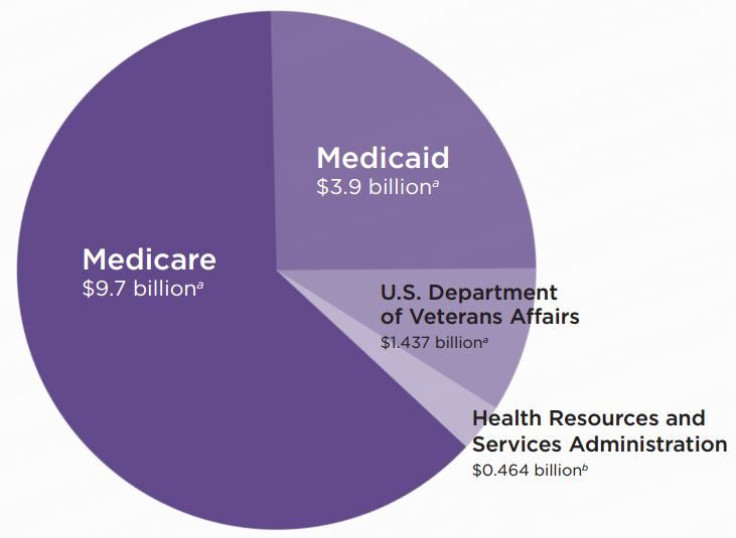

GME payments began 50 years ago with the passage of Medicare, the federal health insurance program for seniors. Today, the bulk of the payments still come from Medicare, although Medicaid, the Department of Veterans Affairs and individual states also chip in.

The payments are generous, and quickly add up at the nation’s largest hospitals. The University of Washington School of Medicine is paid roughly $102,000 per resident. In 2013, the hospital received $32.6 million in 2013 to support 320 residents, making it the state’s largest program in both dollars received and number of residents. Residents there earn about $62,000 a year plus benefits.

Other hospitals earn even more but pay residents a lower percentage of the funding -- the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio received $86.9 million in 2013 for training 728 residents, which amounts to about $119,000 per resident. Residents at the hospital receive a salary of roughly $50,000. Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City was paid $133.8 million for supporting 770 residents. That breaks down to about $173,000 per resident, while the average resident at Mount Sinai earns a salary of about $60,000.

“I think after 30 to 40 years of this kind of funding, it gets pretty addicting,” said Dr. Richard Krugman, a distinguished professor of pediatrics who served as dean of the University of Colorado School of Medicine for more than 20 years.

Proponents of the system say these payments are necessary to persuade hospitals to take on residents. Physicians take longer to conduct surgeries when training a resident, and residents tend to order more tests for their patients than physicians.

“I can see many more patients per hour by myself than if I have a student or a resident with me,” said Dr. J.D. Polk, dean of the College of Osteopathic Medicine at Des Moines University in Iowa.

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission once estimated that teaching hospitals do incur an extra expense of about 2.7 percent for each patient they treat as compared with non-teaching hospitals. However, GME payments are partly based on a formula that covers 5.5 percent of each Medicare bill, which is double the estimated rate of hospital expenses. For that reason, the same group once told Congress that GME payments may be as much as $3.5 billion a year higher than a hospital’s actual costs.

“This is a process of accounting that is more art than science,” Ricketts says. “ I wish I knew where all the money went.”

Gail Wilensky, former director of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and co-chair of the Institute of Medicine committee, argued that GME payments do not primarily serve to cover a hospital’s training expenses in an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine. She and her fellow authors pointed out that even when payments were reduced by $9 billion over five years in the late 1990s, resident salaries stayed roughly the same and positions were not cut. In fact, about half of teaching hospitals nationwide have hired more residents than the federal government pays them to train, creating 12,253 unfunded positions.

"There's no indication that anyone other than the residents bear the cost of their training," she says. "When we've seen significant changes in GME funding, the programs continue and they continue to grow because there are many benefits to the hospital, including prestige, which can allow them to increase the billing rate that they negotiate with third-party payers as a result of being a teaching hospital."

To residents, the math behind the demand for their services is at least clear. Dr. Maahum Haider, 31, is serving her sixth year of a urology residency at the University of Washington. She checks in with an attending physician before and after each surgery, but is otherwise left to perform operations on her own.

“There's definitely a period of time when they're putting in more because we're learning, but I think the learning curve is so steep that it quickly comes to the point where we're giving back much more,” she said. “I think we definitely add value.”

If Chan hadn’t spent all those nights in the lab at Harborview, the hospital might have had to pay a radiologist to complete the work. Radiologists nationwide were paid an average salary of $340,000 in 2013, according to Medscape. Urologists earn slightly more -- $348,000 on average.

“Hospitals don't talk about that,” Mullan says. “Most teaching hospitals can't function without residents. Their costs would go through the roof.”

President Barack Obama has proposed to cut GME payments by more than $16 billion over 10 years -- a proposal that the Republican-led Congress will examine this fall during deliberations on the 2016 budget. The response from hospitals and many physicians groups has been predictably frigid -- the American Medical Association has launched a website called savegme.org in response to previous calls for cuts, featuring videos of residents who plead with viewers to keep funding in place.

Calls For Reform

The IOM committee did not recommend eliminating or even reducing these payments – at least not yet. Their bigger concern was revising the system so that taxpayers know how hospitals spend this money and how much their residency programs really cost. Today, hospitals typically lump the payments into a general operating fund. Even the directors of residency programs struggle to decipher how the money was spent.

“I have no idea how GME is being spent, and I was on the board of the hospital,” said Krugman, formerly of the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Mullan and his fellow committee members recommended creating a GME Center within the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to track the money and lend transparency to the program.

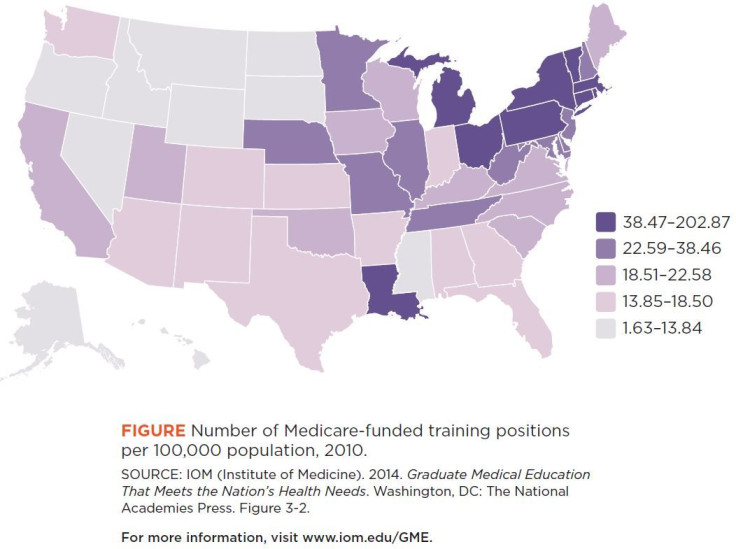

But the group says transparency is not the program's only problem. Currently, GME payments are not contingent on any policy prescriptions or outcomes. The federal government can’t use them to require hospitals to train more primary care physicians or serve rural areas. Only 3 percent of recent graduates from the University of Washington School of Medicine went on to practice in rural areas. One reason is that the formula that determines payments is lopsided and favors urban medical centers over rural hospitals.

Mullan authored a 2013 study published to Health Affairs on this issue. He showed that when adjusted for population, annual payments per person in Montana are a measly $1.94 while the District of Columbia fetches $172.85. For each resident, a teaching hospital in Puerto Rico will only receive $38,294 while a hospital in Connecticut gets $155,135.

“If you look at New York, they get 20 percent of the money and they have 17 percent of the trainees and 7 percent of the population,” he said. Overall, New York hospitals received $2 billion in payments between 2008 and 2010. Less money flows to states which have historically had fewer hospitals or a largely rural population. “California, Texas and Florida are getting screwed," he adds.

Some states have already created incentives to fill this gap and encourage physicians to work in underserved areas -- Iowa repays up to $200,000 of student loans for new doctors who serve in a town of fewer than 26,000 people for at least five years. One of Polk’s surgical residents received an offer from a local town to pay back her loans if she moves there after graduation. He believes more private and local funding could smooth out some of these areas of need.

But those are patchwork solutions, and fail to leverage the heft of billions of dollars in federal payments to meet the nation’s greatest needs. The IOM authors said the government should establish a policy council in the Office of the Secretary at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to set policy priorities and reward hospitals with extra funding if they achieved them.

Despite loud opposition from hospitals and medical schools, there seems to be a stir of interest among policymakers in the committee's recommendations for GME reform.

In Obama’s latest budget request, he asked for $400 million to create a grant program that would reward hospitals for taking steps to fill the shortage of primary care providers and encourage rural service. A few months after the IOM report was issued last summer, the House Energy and Commerce Committee also issued a call for comments on its recommendations. Mullan hopes the committee will call a hearing on the issue soon.

Wilensky is particularly encouraged by the fact that this year, the Association of Academic Health Centers is hosting a series of seven roundtable discussions throughout the country on the topic of GME reform. She will speak at organization's annual meeting in September.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.