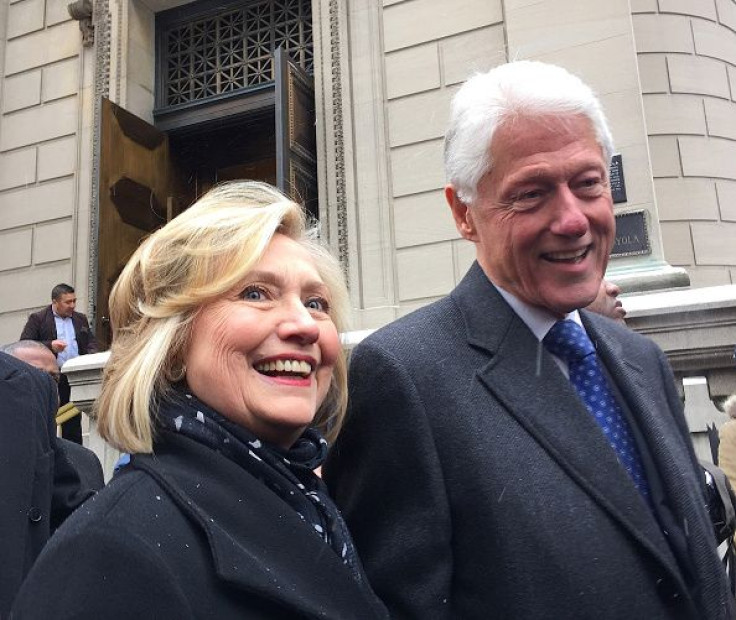

Hillary Clinton 2016: In White House Bid, Hillary Campaigns Against Bill's Legacy

Hillary Clinton is running against her husband’s political legacy. On the campaign trail, the leading Democratic presidential contender has come out firmly in support of same-sex marriage, endorsed a “full and equal” path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants and voiced support for criminal justice reform -- all stances that put her at odds with Bill Clinton’s record in the White House.

Speaking in support of a road to citizenship on Tuesday, Secretary Clinton indirectly rebuked President Clinton’s support of strict immigration controls. As president, Bill Clinton signed a law making it harder for green-card holders to get welfare benefits, and stiffened penalties for undocumented immigrants. Last month, Hillary Clinton similarly broke with her husband's legacy on the issue of “mass incarceration,” decrying the fact that “a significant percentage” of the country’s 2 million prison inmates “are low-level offenders.” But as president, Bill Clinton championed tough-on-crime “three strikes” policies and signed a bill that expanded prison funding and created new mandatory minimum sentences.

While he has since backtracked, in 1996, President Bill Clinton signed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), denying federal marriage benefits to same-sex partners and preventing states from recognizing marriages in other states. On the other hand, the 2016 Clinton campaign backs gay marriage nationwide. Last month, when the Supreme Court took up the issue, Hillary changed the colors of her campaign logo on social media to the LGBT movement’s rainbow pattern.

John Hudak, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, says Hillary’s views on these questions, in part, reflect shifts in public opinion. “I’m not sure Hillary running in 2016 would look anything like Hillary running in 1992,” he says. “Part of it is just changing times.”

In 1996, only 27 percent of Americans believed same-sex marriage should be legal, according to Gallup. In 2014, the public supported gay marriage by a 55-42 margin, the same poll found. National polls, however, reveal that American views on immigration and criminal justice haven't softened in the 14 years since Bill Clinton left the White House, but concerns over those issues have become increasingly commonplace in today’s Democratic Party. In part, that’s the result of recent protests from immigrant rights groups and activists decrying the police killings of unarmed black men.

However, even as the general public has become more liberal, Hudak says, it’s unlikely that Hillary is responding to any pressure from political candidates on the left -- at least not right now. “You usually only respond to forces that are threatening to you,” he says.

Clinton continues to dominate the 2016 Democratic field. In a recent poll for New Hampshire’s primary, she led her only declared challenger, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, by a 54-19 margin. Another recent survey, from Public Policy Polling, found her leading Sanders in Iowa by a 62-14 margin. An avowed social democrat and champion of a federal safety net for the poor and disadvantaged, Sanders represents the left flank of the Democratic coalition. While some of his policy prescriptions may enjoy broad public support, his candidacy has yet to create any major headaches for Clinton.

On welfare and trade, too, Clinton has carefully kept a distance from her husband. When Vox recently asked Hillary Clinton if she supported President Clinton’s welfare reforms -- the culmination of a 1992 campaign pledge to “end welfare as we know it,” her campaign declined to comment. Meanwhile, as the Obama administration aggressively lobbies Congress on fast-track authority and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the former secretary of state has stayed above the fray, declining to take sides. The Clinton campaign has even heralded her public opposition to so-called investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms, controversial third-party tribunals that resolve trade disputes between nations and businesses.

Rep. Alan Grayson, D-Fla., is one of the leading critics of fast-track and the TPP in Congress. He says Clinton’s reticence to back President Barack Obama on trade isn’t based on pressure she’s feeling from trade-wary Democrats. Instead, it’s the tough toll of the landmark North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and recent trade deals like it. “Like all of us, she’s learned from experience,” Grayson says. “She’s feeling pressure from reality.”

The trade deal, implemented in 1994, led to a net loss of 1 million U.S. jobs and has driven a $181 billion trade deficit with Canada and Mexico, according to a report released last year by the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen. Likewise, a 2012 poll found only 15 percent of Americans backed the current terms of the trade deal.

Still, Clinton is walking a tight rope, says Hudak. At the same time as she subtly bucks the Clinton White House on contentious policy debates, she is simultaneously campaigning on her decades of experience, some of which she accrued as first lady.

So far, though, the voters don’t seem to mind.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.