Hong Kong Faces More Protests As Key Reform Vote Nears, But Repeat Of 'Umbrella Movement' Unlikely

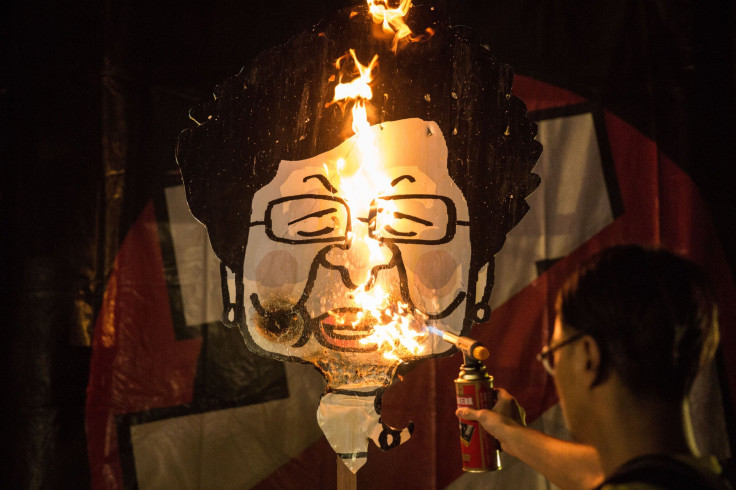

HONG KONG -- As lawmakers prepare to vote next week on legislation that will govern how the region's next chief executive is elected, the city is bracing for the biggest round of protests since the Occupy Central demonstrations paralyzed parts of the Asian financial hub for months last year.

The Hong Kong government's plan -- which was effectively dictated by the central government in Beijing -- would see city voters select the next chief executive by a vote with universal suffrage. There is but one catch. Only candidates approved by a committee packed with Beijing loyalists can stand for election.

Protesters opposed to the bill have planned a five-day rally, due to start Sunday, outside the Legislative Council complex in the city center. But the barricades, long-term occupation of public spaces and occasional violence seen in last year's protests -- dubbed the "Umbrella Movement" -- do not appear likely to return.

“We won't use violence,” Johnson Yeung, vice-convener of the Civil Human Rights Front (CHRF), the group that is organizing the main protest surrounding the event, told International Business Times, on Friday. “Our main objective is to veto the proposal, not to stop the conference,” he added.

However, the prospect of protesters spilling out into the streets, which were blocked for months during the Occupy Central demonstrations, remains, as protest organizers estimate 50,000 people will participate while the primary space allocated by authorities for protests can only reportedly hold 2,600.

“If the capacity of the place is overrun, then there might be some people who occupy roads that we didn't apply for,” Yeung said. “But as long as it's just a minor breaking of the law, it is our right to protest and express our opinion. This is our political freedom.”

Daisy Chan Sin-ying, the convener of CHRF, pledged earlier this week that there would be no return to the roadblocks and long-term occupation of public spaces that characterized last year's protest movement, according to the South China Morning Post.

The electoral reform proposal plan has divided the city. The results of a rolling poll conducted by three Hong Kong universities were released Wednesday, and revealed that voters were evenly split on the proposal for the first time -- with 43 percent supporting the plan and 43 percent opposing it.

Despite the even public split on the vote, it is almost certain to be voted down -- with a group of pro-democracy lawmakers that have enough votes to block the measure all pledging to oppose it.

The authorities, however, are taking no chances. Hongkongers are “highly concerned another round of occupation could take place," the city's Secretary for Security Lai Tung-kwok said Thursday.

Police sources cited by the Post said that over 7,000 officers -- some equipped with riot gear, rubber bullets and pepper spray -- will be on hand to respond to disturbances, and that demonstrators who occupy roads would be immediately removed.

With the goal of last year's protests -- allowing members of the public to nominate candidates for the post of chief executive -- firmly rejected by the central authorities in Beijing, pro-democracy activists in the city have only one way to vent their frustration: working to vote down Beijing's proposal.

China's central government has been unusually vocal in the public discourse over the proposed reforms, running two editorials in state-run newspapers. In addition, a senior official has warned pro-democracy lawmakers in the city of dire consequences if they rejected the package.

With the proposal facing a likely defeat, and the Beijing government seemingly set firmly against further reforms, democracy activists in the city face an uncertain path toward achieving their goals.

“We never know when we will have the advantage. We just have to keep going on,” Yeung said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.