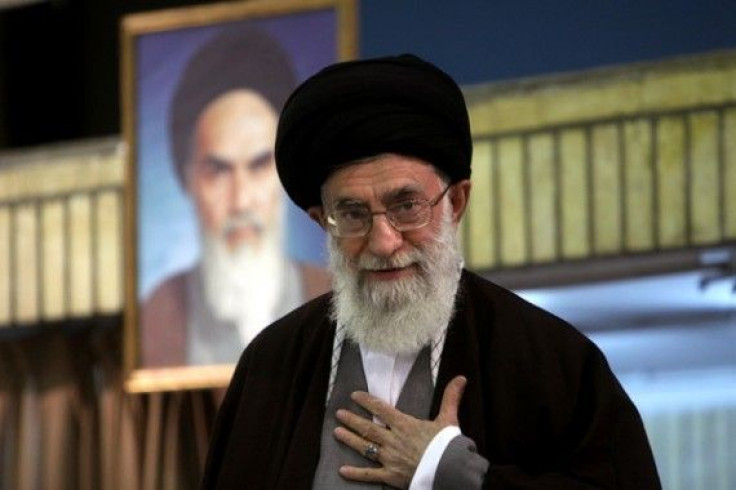

Hooshang Amirahmadi: Iran's Next President Or Another Reformer To Be Stifled By The Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei And Iranian Clerics?

For a man who comes from a country where most people have to exploit loopholes to get around the strict censorship of the Internet, Hooshang Amirahmadi is remarkably Web-savvy.

He’s already run a Reddit AMA, Internet slang for taking questions, town-hall style (“Ask Me Anything”) on one of the Internet’s most popular open forums. He has a graphic design contest for his upcoming political campaign through his Twitter account and an English-language Facebook page, which has more than 1,500 likes. His Facebook page in Persian has 4,350 likes since it launched in the middle of March. It's certainly an unorthodox approach for a man who wants to be the next president of Iran.

A 65-year-old Iranian-American with a Ph.D from Cornell in planning and international development, Amirahmadi said he’s always been interested in politics, but it wasn’t until some 15 years ago, soon after founding the American-Iranian Council, a Princeton, N.J.-based advocacy group, that he decided running for office was a good idea.

“When it comes to actions on the ground, it’s only a small group of people who move societies. These are the people either making or influencing decisions,” said Amirahmadi, who has been teaching at Rutgers University’s Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy since 1983. “To actually be effective and do something, you need to be in a position of decision-making and power.”

Amirahmadi has never held an elected position before, and he’s never been a member of an Iranian political party. However, he has previously run for office in Iran, or at least tried to: In 2005, he put his name on the ballot for Iranian president. It was a time, Amirahmadi said, when Iranian intellectuals were boycotting the elections. He didn’t want “to go down in history as someone who stayed away from that election. That election became a turning point in Iran’s history.”

In case you missed it, Amirahmadi didn’t win the 2005 election. In fact, Iran's Guardian Council, the supreme ruling body of clerics, disqualified him because of his dual Iranian/American citizenship. Current President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won that race, an election that attracted one of the lowest turnouts in the history of post-revolutionary Iran. In the subsequent eight years, Iran has increasingly become a pariah state, accused of backing terrorist groups around the world, refusing to cooperate with the U.N. or other international bodies, and developing a much-condemned nuclear program. Ahmadinejad won again in 2009 in an election that many believe was fraudulent, tilted by Iranian's clerics toward the incumbent. Large numbers of Iranians protested the outcome of the election to no avail. In the wake of Ahmadinejad's two victories, the Iranian emigration rate spiked noticeably.

The next election will be in June, and Amirahmadi is surprisingly optimistic about his prospects, despite general skepticism that the contest won't be on the up and up. “I am told by many in Iran that if I am approved by the Guardian Council, no one can compete with me,” he said.

Indeed, this time, Amirahmadi isn’t just submitting his name to make a statement; he's taking the contest seriously. Even though official public campaigning doesn’t start until the end of May, Amirahmadi and his team have been on the road and on the Web since the end of November. “I am way ahead of the competition,” the candidate said. His campaign has already visited Dubai, London, Scotland, Northern Ireland and several locations in the U.S., including Vermont and New York. He said the reception by Iranian expatriates has been “incredible.”

“I have tried to make it a global campaign because Iran is a global issue. We need to see a different Iran, a better Iran,” he said. “The international community is tired of seeing Iran being in the news every day for 30 years for the wrong reasons.”

The restrictions on campaigning haven’t stopped him inside of Iran, either. Amirahmadi’s been busy with interviews in the Iranian media and holding private events for academics and other potential supporters. “We are well known in the universities and in the intellectual and professional communities,” he said. “All of what we do gets translated in Iran, so even from here we are talking to all Iranians.”

That message might be getting a bit lost. Nagmeh Sohrabi, another Iranian-American professor, who teaches Middle East History at Brandeis University in Boston, said she was recently talking to several friends in Iran who had no idea who Amirahmadi was. “They’ve lived all their lives there, they’re aware of the political system, and they didn’t know who he was,” Sohrabi said. “These are regular people who are highly educated, and they’ve never even heard that this guy is running.”

For her part, Sohrabi said that if she votes, she probably won’t vote for Amirahmadi. While Amirahmadi’s candidacy could be “productive,” she said, and certainly raises important issues, the act of voting in Iranian elections is complicated for expats who don’t plan to move back. “I have to think about what my vote means,” she explained. “Is someone who lived outside for 40 years and has concerns that are shaped by that experience necessarily the best person for people inside Iran?”

Amirahmadi’s candidacy does have Sohrabi “intrigued,” she said. “On the one hand, I don’t think anyone who knows the Iranian political system thinks that he has any kind of chance getting his candidacy approved by the Guardian Council,” she said. “On the other hand, he’s taking it very seriously. There aren’t many people [who] would take it as seriously if they were in his situation. It’s interesting to watch unfold."

If the Guardian Council disqualifies Amirahmadi, it could again be because of his dual citizenship, but the unstated reason will be because he dares trumpet progressive ideas as gender equality, freedom of the press and freedom of religion. For example, in his “Ask Me Anything” session on Reddit, Amirahmadi said that “in my administration, there will be no restriction on any type of media. I believe in free speech,” in response to a question about websites like Reddit being blocked in Iran.

When asked about the rights of women and the LGBT community in Iran, Amirahmadi was similarly Western in his view: “My policy is very simple,” he wrote. “Every Iranian citizen regardless of their religion, ethnicity, race, color, gender, has all the citizenship rights and obligations. All of them are equal in front of the law.” He said he saw homosexuality as “a non-problem.” He also admitted that the situation of women’s rights in Iran was “far from desirable,” but that he “plans to name a woman as vice president.”

If this came to pass, she would be Iran’s first female VP.

And about relations with the U.S., the country that the Islamic Republic’s rulers routinely call the Great Satan, Amirahmadi is equally heretical. He said rebuilding lines of communication with the U.S. would be “a top priority,” and that he is categorically “against nuclear weapons.”

“Iran signed the safeguard agreement and the Non-Proliferation Treaty,” Amirahmadi said in an interview with International Business Times. “We have a right to civilian nuclear technology, but [Iran] has that right within the obligation it has made [to not develop nuclear weapons].

“The key is transparency,” he said, taking a stance completely opposite to the current Iranian administration, who routinely refuses to allow U.N. inspectors into the country. “Iran has to do whatever it has to do in complete transparency.”

An Iran open and transparent on nuclear technology would certainly sit very well with the U.S. and Israel. And speaking of Israel, Amirahmadi would offer a different view on the Jewish state than Ahmadinejad’s current policy on what he calls “the Zionist entity.”

“Israel is a reality,” Amirahmadi said. “It has to be recognized as a reality. I would be for an Israeli state as long as there’s a Palestinian state.”

On Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad, whom the Iranian regime has been supporting militarily in its civil war against rebelling citizens, Amirahmadi fell in line with the position of most of the international community: “The Assad government has to go,” he said. “That family has been around for too long. Their hands are filled with Syrian blood.” He also acknowledged that an end to Assad was not an end to the problem in the country. “Unfortunately there are bad guys on the other side,” he said. “We need to be very careful with that.”

The campaign’s communications director, Kayvon Afshari, agreed that Amirahmadi’s message is “progressive,” but said he would not classify it as “Western.”

“His positions are a clear reflection of the values and beliefs of the Iranian people,” Afshari wrote in an email. “The obstacle before us is not the support of the Iranian people; it is the approval of the Guardian Council.”

Amirahmadi’s campaign is moving back to Iran to begin low-level activities at the end of March. However, if he does run, the outcome of the election will likely depend less on the Iranian people, and more on the favor of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran. As Karim Sadjadpour, a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for Peace, put it at a talk at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York in early March: Iranian elections always come down to “one man, one vote, and that’s Khamenei.”

Amirahmadi is realistic about that. “I wouldn’t say (the election) is his decision, but obviously he’s the major person,” he said. “The president of the country has to work with him, so Khamenei has to trust him.”

Part of the problem in Sadjapour's view, is that the Ayatollah “hasn’t left Iran since 1989. He’s frozen in time, and his hostility toward the U.S. and toward Israel is cloaked in ideology and driven by self-preservation.” A Westernized professor and his hypothetical female vice president might not be welcome in such a situation. If the disputed Ahmadinajad election of a few years ago, when opponents were effectively muzzled, is any indication, the government has a precedent of stifling the hopes of reformer candidates. Amirahmadi is unabashed about his desire to reform Iran, and will not be changing his progressive tune once in-country campaign season begins.

“Dr. Amirahmadi is campaigning with the same consistent message in both Iran and outside the country,” Afshari confirmed. “Dr. Amirahmadi's core platform of resolving domestic factional infighting, promoting dialogue with the United States and addressing the economic malaise is the same whether he is in New York or Tehran.”

Further stumbling blocks could be nepotistic tendencies at play in Iran. On Wednesday, Esfandiari Rahim Mashaei, Ahmadinejad’s right-hand political man, gave a key speech during Iranian New Year celebrations in Tehran, a spot that was supposed to be reserved for the president. "Ahmadinejad doesn't want to go out with a whimper. That's not his style," Mustafa Alani, an analyst at the Gulf Research Center based in Geneva, told the Associated Press. "He wants his legacy, his man, as his successor."

Since Ahmadinejad has generally fallen out of favor with the Guardian Council, he may not have that much say over who gets the top spot next. As Amirahmadi sees it, the Iranian people are pinning their hopes on this being true. “Iranians want change, real change,” he said. “They are tired of 30 years of war, sanctions, isolation, factional in-fighting, bad economic policies, declining industries, growing unemployment and rising prices. Iranians just want their lives normalized.”

In a few months, we'll find out whether Amirahmadi is the type of “normalized” for which Iran, and its leadership of clerics, is looking.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.