How Sex, Drugs And Smuggling Could Rescue Italy’s GDP

Sex, drugs and smuggling could give Italy’s economy a much-needed economic boost this year, as national statisticians incorporate the country’s underground markets into its calculations.

On Friday, the Italian National Institute for Statistics said it would include drugs, prostitution and smuggling in its calculation of Italy’s 2014 GDP recalculation, which should help Prime Minister Matteo Renzi achieve his dream of narrowing the country’s deficit to 2.6 percent of the GDP, according to Bloomberg.

“The size of the shadow economy might have surprised some readers if they had seen these estimates two or three years ago,” they wrote. However, the recent Euro crisis “has shone a spotlight on problems in these countries with regard to tax collection and compliance and the problems are more widely known.”

In Italy, this kind of activity accounts for roughly 20 percent of its total GDP, but these illegal activities account for roughly 18 percent of the entire European Union economy, according to a study by economists Friedrich Schneider and Colin Williams.

Underground markets are a natural part of every country’s economy but are typically larger in countries with higher tax and social security burdens, as well as stricter restrictions on labor markets. Schneider and Williams estimate that in Europe, the more developed countries bear more than two-thirds of total underground activity.

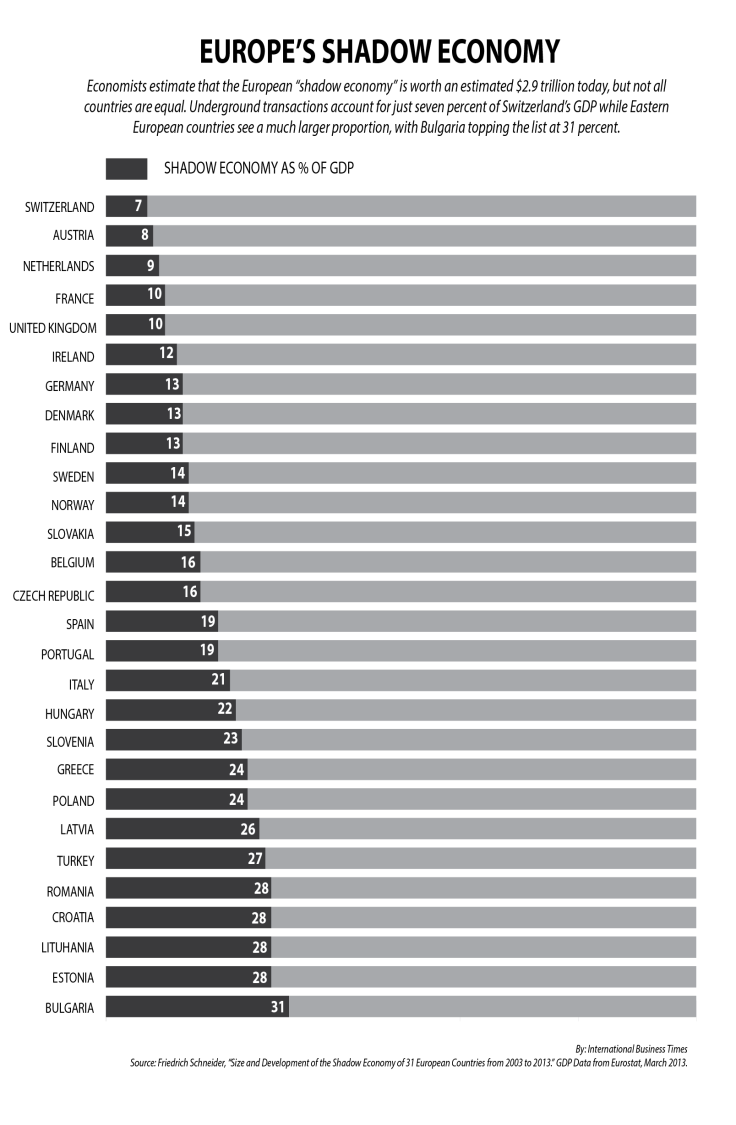

While Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom have the biggest shadow economies in Europe, when calculated as a percentage of GDP Eastern European countries such as Bulgaria, Estonia, Lithuania, Croatia and Romania have the highest rates.

Though exact data isn’t available, the economists estimate that there were more than 30 million people involved in shadow work in the European Union by the end of the 20th century, and Italy isn’t the only one to include it.

“Owing to the big increase in the size of the shadow economy in value-added terms, a number of countries adjust their national accounts to include estimates of shadow economic activity,” they wrote.

Russia makes the largest adjustment, at 24.3 percent, while the United States adjusts the least, at just 0.8 percent, according to their data.

But it’s not all bad. High levels of shadow economic activity don’t always mean a reduction in welfare, and still contribute to a person’s income, and usually even goes into the formal economy.

“It is therefore important not to try to stamp out the shadow economy by stamping out the economic activity that goes with it – throwing the baby out with the bathwater, so to speak,” they wrote.

“Economic activity is, after all economic activity.”

There are many different types of shadow markets. Illegal ones include trade in stolen goods, drug dealing and manufacturing, prostitution, gambling, smuggling, human trafficking, drug trafficking and fraud. But legal activities such as employee discounts, paid handiwork and neighborhood help can also contribute.

This kind of activity tends to correlate with larger economic cycles, according to another report from Schneider in conjunction with Visa Europe and researchers from A.T. Kearney, an advisory firm. This is especially pronounced during hard times.

“During times of economic downturn, rising unemployment, lower disposable income and fears about the future, more individuals tend to drift into ‘shadow activities’,” the report says. People are more likely to take on an extra job which they may not report, or may underreport profits to help with personal finances.

A prime example is the financial crisis in 2008. By 2009, the shadow economy increased 0.5 percent relative to GDP, breaking a long-term decline.

“While more individuals sought alternatives to the official economy, the shadow economy could not compensate for the decline in the real economy,” the authors wrote.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.