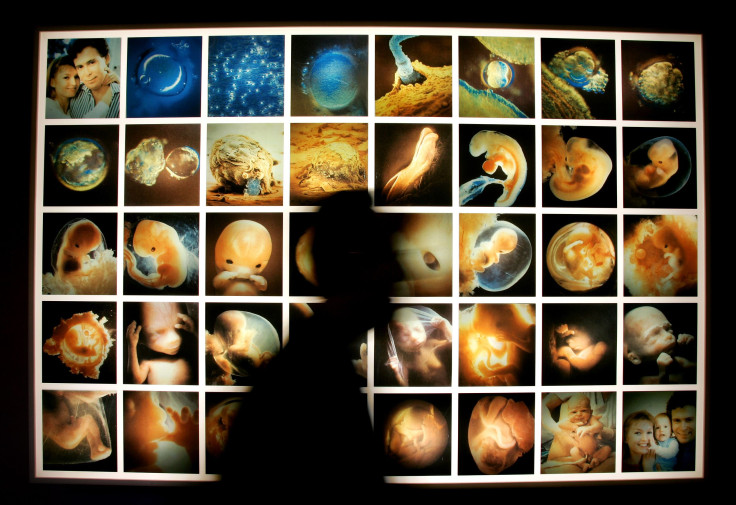

Human Embryo Genetic Modification: UK Researchers Seek Permission For Controversial Technique

A team of British scientists have sought permission to genetically modify human embryos for the first time ever, a technique currently embroiled in controversies. The request comes in the wake of a gene modifying experiment recently conducted by Chinese scientists -- which triggered a debate over the ethics of genetic therapies -- and a statement by an international group of scientists calling for the genetic alteration of embryos to be permitted for research purposes.

“The work carried out at the Crick [the Francis Crick Institute] will be for research purposes and will not have a clinical application. However, the knowledge acquired from the research will be very important for understanding how a healthy human embryo develops,” the London-based institute said, in a statement Friday. “This knowledge may improve embryo development after in vitro fertilization (IVF) and might provide better clinical treatments for infertility.”

The technique, if permitted by the U.K.’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), would see the first genetically modified embryos created within months, the Guardian reported.

“We have recently received an application to use Crispr/Cas9 (gene editing) in one of our licensed research projects, and it will be considered in due course,” a representative for HFEA reportedly said.

If the request goes through, it would be the world’s first approval for such a research by a national regulatory body.

The first report of the Crispr/Cas9 technique being applied to human embryos emerged in April, when a team of Chinese scientists showed -- through a partially successful experiment -- that errors in the DNA that cause beta-thalassaemia, a life-threatening blood disorder, could be corrected through gene modification in early stage embryos. The study, published in the journal Protein and Cell, triggered widespread outcry, with several critics calling it a move toward the so-called “designer babies.”

While most scientists and researchers believe that embryonic genome editing should not be used for reproductive purposes at present, they have spoken out in support of research in the field.

“What is needed is not to stop all discussion, debate and research,” Debra Mathews, assistant director of science programs at the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics and a member of the Hinxton Group -- an international group of scientists and policy experts -- said, in a statement released earlier this month. “But rather to engage with the public, policymakers and the broader scientific community and to weigh together the potential benefits and harms of human genome editing for research and human health."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.