Inbreeding Common In Early Humans? Skull Deformities Suggest It Was All In The Family

Fossilized pieces of skulls from an early human that lived 100,000 years ago bear defects that suggest early hominid families may have been more intimate than is generally accepted today.

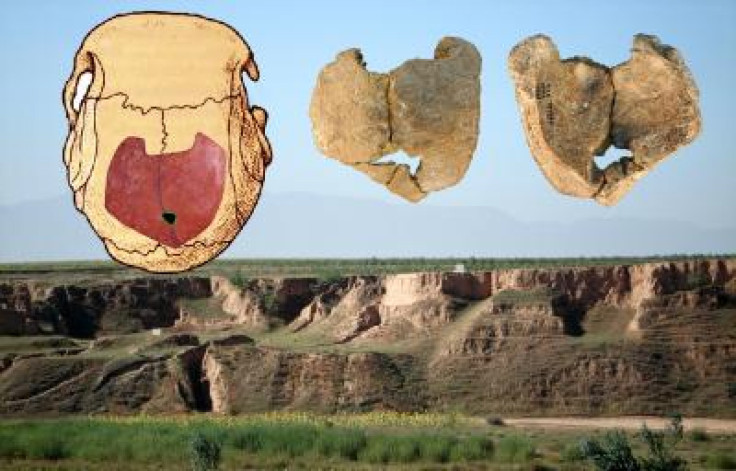

Researchers unearthed the skull pieces, dubbed Xujiayao 11 after the site in China where they were found, in the 1970s. In a paper published on Monday in the journal PLoS ONE, scientists took a closer look at the fossil using advanced digital and scanning electron microscopes.

They found that the skull had a perforation known as an “enlarged parietal foramen,” or EPF, running along the top of the brain case. Scientists know now that this deformity is associated with a pair of rare genetic mutations that interfere with bone formation. The perforation arises in about one of every 25,000 births, and occurs during fetal development when small holes on the back of the skull fail to close.

Luckily for the early human that owned the ancient skull, the defect seems not to have hindered him or her too much: the individual reached adulthood.

This isn’t the first EPF that researchers have found in the bones of early humans from the late Pleistocene. Genetic anomalies crop up throughout the fossil record of human history, even in earlier ancestors like Homo erectus.

"The probability of finding one of these abnormalities in the small available sample of human fossils is very low, and the cumulative probability of finding so many is exceedingly small,” coauthor and Washington University in St. Louis anthropologist Erik Trinkaus said in a statement Monday.

Basically, it’s very unlikely that so many rare genetic mutations would occur in a population through regular breeding dynamics. Inbreeding makes it much more likely for recessive traits like the mutations that cause EPF to flourish. Our ancestors lived through tough times that may have restricted their choice of mate to whoever was nearest, thereby forcing them to keep it all in the family.

But if early humans did inbreed quite often, that might force researchers to reevaluate some of their theories about human evolution. Many of these genetic models assume that humans existed in large, stable populations, Trinkhaus told LiveScience.

“It remains unclear, and probably untestable, to what extent these populations were inbred, but close genetic relationships have been suggested for one Neanderthal sample and some Upper Paleolithic burial groups,” Trinkhaus and his colleagues wrote.

SOURCE: Wu et al. “An Enlarged Parietal Foramen in the Late Archaic Xujiayao 11 Neurocranium from Northern China, and Rare Anomalies among Pleistocene Homo.” PLoS ONE published online 18 March 2013.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.