Income Gap Grows Quickly Over Past Two Decades For Prime Working Age Professionals: Personal Finance Advisor

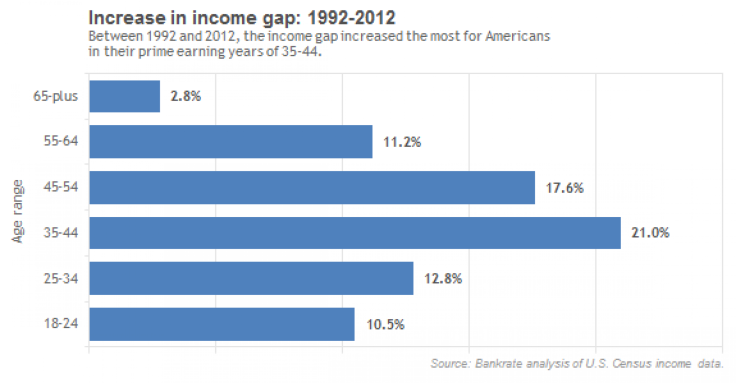

Income gaps rose the fastest in the past 20 years among U.S. residents aged 35 to 44, a career window where workers often make their retirement fortune or stand defeated by heavy living costs, according to a recent Bankrate.com study.

Personal finance firm Bankrate Inc. (NYSE:RATE) sourced federal income data from the U.S. Census, mapping the years from 1992 to 2012. That showed income gaps widening 21 percent for 35-44-year-olds and 17.6 percent for 45-54-year-olds, suggesting that midlife professional careers are where incomes are importantly made or broken.

Surprisingly, the income gap for the elderly grew most slowly, at 2.8 percent for people over 65.

Still, seniors show the largest actual income gap, even if that’s been slow to expand. That income gaps are the largest among seniors isn’t surprising and is line with historical trends, Bankrate analyst Chris Kahn told International Business Times.

No age groups saw income gaps decline, in an indication of broadening U.S. income inequality.

Differences between what U.S. workers earn is higher than the average wage gap in Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) industrialized nations, according to a May 2013 report.

In 2008, the U.S. was the third-most-unequal nation in terms of pay in the OECD, after Mexico and Turkey. That was a trend started in 2000, according to the bloc.

Bankrate’s analysis doesn’t capture the wealth gap, which measures for home values and stock assets, too. The U.S. housing crash and financial crisis likely hit middle-aged workers hard, too, according to experts interviewed by Bankrate.

“There’s a good correlation here between income gaps and wealth gaps,” added Kahn.

Wealthy U.S. investors may have gained even more wealth in stock markets, especially as U.S. equities hit repeated records this year. Lower earners may have invested less in risky assets, assuming they could afford them. A U.S. housing recovery, set to benefit a broader cross-section of Americans, has proceeded more slowly than stock rallies.

High unemployment, now at 7 percent in the U.S., alongside stagnant wages and rising living costs, make it tough for people aged 35 to 44 to grow incomes, according to Kahn.

In America broadly, the bottom fifth of households earns about $11,500 annually on average, while the top tier earns almost $182,000.

“You can’t talk about the income gap without talking about stagnant wages, and the decline in America’s unions,” continued Kahn, who referenced President Barack Obama’s speech last week on raising the federal minimum wage.

Kahn said a U.S. economy that has sent manufacturing and service jobs overseas, a low-earning but expanding immigrant population, and inheritance tax rules have all added to income inequality.

A November 2013 Pew Charitable Trusts report found that only 4 percent of Americans have a “rags to riches” story, with 70 percent of poorer Americans never making it to the middle class. Education, race and two earning parents were key factors impacting economic mobility.

“There are so many ways to explain why America’s income gap is growing,” said Kahn.

Even as inequality continues, net wealth in the U.S. rose to $77 trillion in the third quarter, a new record high, according to a Capital Economics research note on Tuesday. Household debt rose by $100 billion, however, as homeowners took on more mortgage debt.

Rising equity and home prices contributed to the gains, said the London-based economic researcher. Rising wealth and higher incomes also mean that U.S. consumers will spend more in 2014 and 2015, they wrote.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.