India 2012 Budget Lacks Teeth; Congress Party Is Too Weak To Act

Analysis

Although India's proposed 2012 budget contains a few welcome provisions, the plan presented Friday offers no assurance that the ruling Congress party will make meaningful policy changes to tackle structural problems in the country.

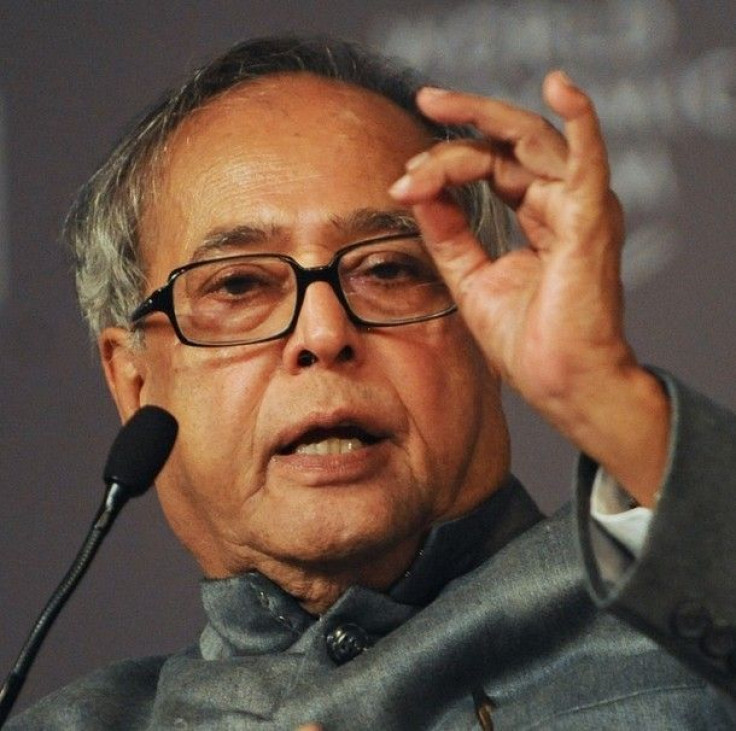

In his budget speech to the Indian parliament, Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee proposed lowering the deficit for the next fiscal year, which starts April 1.

He forecast a deficit of 5.1 percent of gross domestic product, which is lower than the 5.9 percent gap expected this year.

Experts, however, expressed skepticism over the prediction.

Although the assumptions underpinning the 2012-13 forecast are more realistic than they were this time last year, we are still looking for another fairly substantial overshoot, Robert Prior-Wandesforde, director of Asia economics at Credit Suisse, told the Wall Street Journal.

Last year, the Indian government had forecast the budget deficit would be 4.6 percent of GDP, a figure substantially lower than what Mukherjee now expects.

One way the minister hopes to cut government spending is by limiting subsidies on food, fertilizers and petroleum products to 2 percent of GDP. In the current fiscal year, subsidy costs soared, partly due to higher oil prices.

The subsidy cap of 2 percent of GDP set out in today's Indian budget would be positive for the country, wrote Art Woo of Fitch Ratings.

But Woo doubts India's willingness and ability to hit the 5.1 percent deficit target.

Another proposal Mukherjee presented Friday was raising service and excises taxes to 12 percent from 10 percent. That, too, is a good idea in theory, Woo said.

Other proposals included more spending on infrastructure and a capital-gains tax on foreign investors applied retroactively to 1962.

Implementation fears aside, some also criticized Mukherjee's plan for being too timid.

It's a nowhere budget, Meghnad Desai, a London School of Economics professor emeritus, told the Financial Times. It doesn't take the economy forward. It's shocking that a finance minister can get up and ignore all the problems that he faces.

India's economic growth is expected to flag to 6.9 percent this fiscal year compared with 8.4 percent in each of the two preceding years.

The country faces serious economic challenges, including high inflation (6.95 percent year on year in February) and limited access to capital in the private sector.

India's dysfunctional government, long accused of inefficiency and even corruption, is at the root of these problems, critics allege.

Mukherjee on Friday, for example, didn't address whether India would permit foreign direct investment in multi-brand retail and aviation, Sunil Duggal, chief executive of consumer-goods maker Dabur India Ltd., was quoted by the BBC as saying.

A common lament of experts is that India's bloated government crowds out and distorts the private sector. Currently, however, the Congress party seems unlikely to tackle tough, structural problems, even though political leaders are well aware of them.

Congress, to which Mukherjee belongs, suffered embarrassing losses to regional parties in state elections earlier this year, signaling the increasing fragmentation of Indian politics. And a nationwide general election looms in 2014.

Weakened and uncertain, the party seems unable or unwilling to take bold action.

Swapan Dasgupta, a political commentator, characterized the budget proposed Friday as a political survival strategy, the FT reported.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.