Inside The Mind Of A Neanderthal: Symbolic Bone Shows How Similar Their Brains Were To Ours

Neanderthal bones can tell us how these human ancestors evolved and what they looked like, but they can’t tell us how their brains worked. A different kind of bone can.

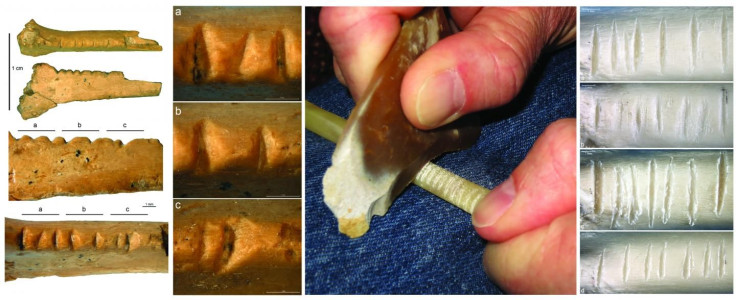

Scientists have uncovered the bone of a raven that they say was decorated in a way that opens a window into how Neanderthals were thinking. The study in the journal PLOS One describes that after making notches in the bone with a stone tool, its Neanderthal carver went back and drew two more notches to make the spaces between them more even. This shows the person was discerning spacing similar to how modern humans do and “neuromotor control allowed them to master the techniques and motions necessary to obtain regularity when required.”

Read: Fossil of an Ancient Head Tells Us How Neanderthals and Humans Evolved

Analysis of the bone, discovered in Crimea, showed that the second and sixth notches were added to close gaps between the first and third notches and the fifth and seventh notches, respectively.

“Even if the production of the notches may have had a utilitarian reason, the notches were made with the goal of producing a visually consistent pattern,” according to the study. The researchers know this because their analysis indicates that “adding of the two very small and superficial notches added virtually nothing to the gripping power of the object’s surface.”

Knowing about the thoughts of Neanderthals can tell us more about how we evolved. A purely symbolic decoration of a bird bone is evidence of a certain level of cognition comparable to ours.

There are other factors that suggest Neanderthal brains were not far inferior to those in the first modern human skulls, such as the fact that Neanderthals and modern humans mated. “Such an outcome would arguably be unlikely in the face of major cognitive differences and if, for example, language was absent,” the authors wrote. Neanderthals were also skilled hunters, could “ignite and control fire” and organize their habitations.

Modern humans replaced Neanderthals somewhere around 30,000 years ago.

See also:

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.