Iran’s Nukes: Born Out Of Pride, Iran’s Nuclear Program Has Become A $100 Billion Habit To Sustain Ayatollah Khamenei’s Ego

World leaders from the P5+1 group -- Britain, China, France, Russia, the U.S. and Germany -- are meeting in Almaty, Kazakhstan, beginning Friday to once again try to talk Iran back from escalating its nuclear development. The talks probably won’t accomplish much. Last time the six met, in Istanbul in March, the talks were “the most substantive to date,” American officials said, but the Iranians still refused any of the conditions of shutting down production in the Fordow nuclear facility in exchange for an easing of economic sanctions.

A Chinese Foreign Minister told Xinhua on Wednesday that all concerned parties must take “practical action,” diplomat-speak for “We’re down to the wire.” Talks will take place Friday and Saturday and are expected to discuss a “revised proposal” that basically offers the same deal: Stop enriching uranium, shut down production at Fordow, and in exchange the West will offer “limited sanction relief,” Xinhua reported.

Iran’s position on this has always been that as a signatory to the Non-Proliferation Treaty, it has a right to develop nuclear energy for peaceful purposes. Most Iranian statements coming ahead of the talks have been on the positive side: A spokesman for the Foreign Ministry told the state-run Press TV that coming to an understanding in these talks “is easily reachable.”

It may be easily reachable, as long as Iran can continue enriching uranium. A new study from the Carnegie Endowment for Peace in Washington makes the case that Iran has sunk too much pride, money and time into its nuclear development to back off that easily.

Since Iran began nuclear development in earnest in 2002, the program has cost the country more than $100 billion, the report said. One of the most expensive nuclear facilities in the world, the Bushehr reactor, cost $11 billion to build and provides only 2 percent of Iran’s power. Bushehr officially opened for business in September 2011. Iran’s oil revenue, meanwhile, fell $40 billion in 2012. Canceled energy contracts cost the country $60 billion in 2010. The Iranian rial, the national currency, lost 80 percent of its value between 2011 and 2012, the study said. In addition, Iran has very little naturally occurring uranium on its land, and what's there is of low quality. These factors “inevitably compel Iran to rely on external sources of natural or processed uranium,” the report said, further driving up the cost and negating the idea that nuclear power could be a cheap, sustainable source of energy for the country.

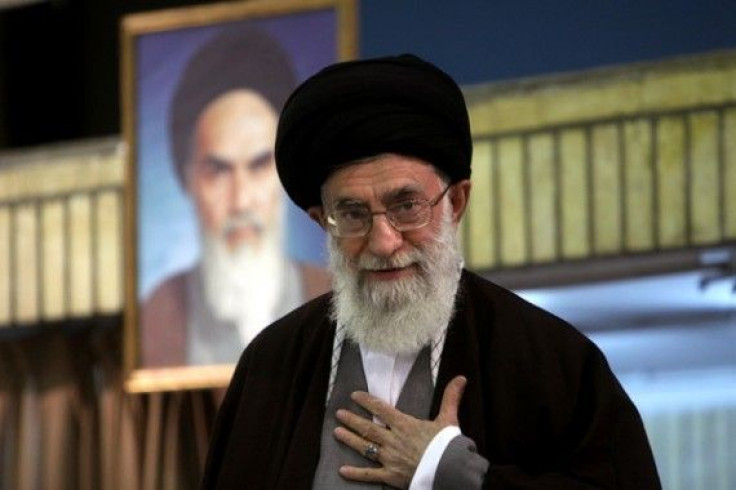

In spite of the sanctions and warnings that there are “more drawbacks than benefits” to a nuclear breakout, this is a matter of pride for Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei. He has sunk too much money and time into his pet project -- the birth of Iran as a nuclear state -- to back down.

Speaking at the Council on Foreign Relations in March, Karim Sadjadpour, a co-author of Carnegie’s study and the author of Reading Khamenei: The World View of Iran’s Most Powerful Leader, recounted a conversation he had with a few members of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard. "They drew this, you could argue, facile lesson from Pakistan," he recounted. "When Pakistan actually detonated a bomb, it turned outside pressure into outside engagement. The world was forced to deal with them. It became ... a fait accompli that they were a nuclear power." As such, he concluded, Iran believes that demonstrating nuclear capabilities will force the world to acknolwedge it as a world power.

One thing the West has to understand about Khamenei is that the man hasn’t left Iran since 1989. “He’s frozen in time,” said Sadjadpour. Khamenei’s myopic view of the world is one huge reason negotiating with Iran has been nearly impossible. "I think the challenge with Khamenei is that his hostility towards the U.S. is cloaked in ideology, but I would argue it's driven by self-preservation," he explained.

This is part of the reason why economic sanctions have not been an effective deterrent. “This is a regime which has long been willing to subject their population to pretty severe economic hardship to avoid compromising,” Sadjadpour said. “[Khamenei’s] modus operandi is never compromise. If you compromise, that’s going to project weakness.”

“I don’t see us being able to reach a grand bargain with Iran,” Sadjadpour continued. “But we don’t need to go to war.”

If Friday and Saturday’s talks are as successful as China, Russia and Iran are hoping, there are a few ways out, as proposed by Sadjapour and the study’s co-author, Ali Vaez. One would be emphasizing “public diplomacy” alongside nuclear diplomacy -- that is, bringing Iran back into the fold of prosperous nations who cooperate with the U.N. and the West. “Washington should clarify what Iranians would collectively gain by a nuclear compromise,” the report said. “A prosperous, integrated Iran is in America’s interests.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.