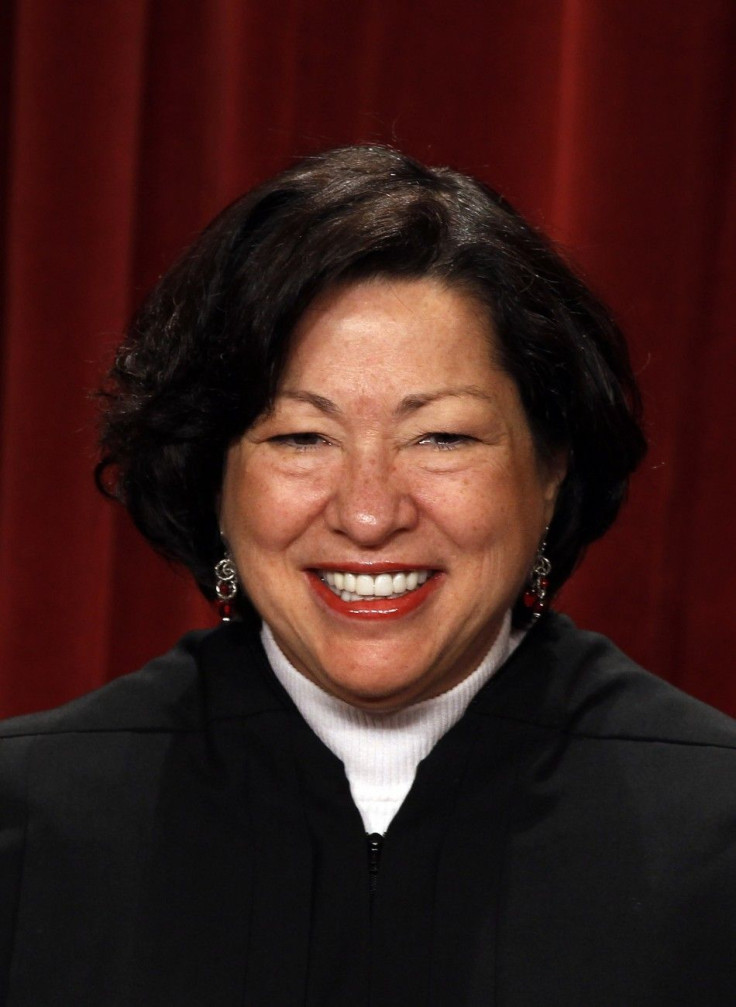

Justice Sotomayor Shows Concern For 'Ordinary People' In Supreme Court's Arizona Immigration Law Case

When President Barack Obama tapped Sonia Sotomayor to be his first pick for the U.S. Supreme Court in 2009, he said she had something more than just intellectual heft and a commitment to impartiality.

A Puerto Rican born and raised in a South Bronx housing project, Sotomayor -- who once called herself the perfect affirmative action baby -- graduated from Princeton with honors and received her law degree from Yale, where she headed its prestigious law journal.

It is experience that can give a person a common touch and a sense of compassion; an understanding of how the world works and how ordinary people live, Obama said in May 2009 when introducing Sotomayor, the first Hispanic to sit on the nation's highest court.

That mindset was on display Wednesday when Sotomayor took the lead in articulating concerns about civil rights abuses in a case over Arizona's unprecedented immigration enforcement law.

The most controversial part of the law is a provision Hispanics and civil rights groups call papers please, which requires law enforcement to inquire on the status of a detained person if there is reasonable suspicion they are in the country illegally. This has prompted fear in Hispanic and civil rights communities that it will lead to racial profiling.

But discussion of racial profiling was off limits during Wednesday's oral arguments. Instead, Sotomayor's line of questioning focused on what U.S. citizens and immigrants alike would go through should Arizona's law, known as S.B. 1070, goes into effect.

A Curious Justice

I'm just realizing that I don't really know what happens when the Arizona police call the federal agency to aks about someone's immigration status, Sotomayor said in a moment of candor.

The process was critical information for Sotomayor and perhaps her fellow liberal on the court, Justice Stephen Breyer, both of whom were concerned that suspected undocumented immigrants, even American citizens, would be detained longer under the Arizona law. That extended detention could violate a person's constitutional right against unreasonable seizure.

She pressed the government's lawyer, Solicitor General Donald Verrilli, to explain how immigration status is checked. According to Verrilli, a federal agency will cross check a name against eight or ten different databases ... to see if there are any hits.

Well, how does that database tell you that someone is illegal as opposed to a citizen? Today, if you use the names Sonia Sotomayor, they would probably figure out I was a citizen. But let's assume it's John Doe, who lives in Grand Rapids. So they are legal. Is there a citizen database?

Aside from checking a database of passports, Verrilli explained that there is no database that lets federal agents know immediately who is a legal U.S. citizen.

So if you run out of your house, she said, without your driver's license or identification and you walk into a park that's closed and you're arrested, they make the call to this agency. You could sit there forever while they figure out if you're [a citizen.]

Benny Agosto, a Texas lawyer who is the president of the Hispanic National Bar Association, said she strongly articulated the possible injustices that can happen in an imperfect system.

It's not just the black-and-white part of the law. It's, what is the result in practice, Agosto said. That shows her 'real life' thoughts -- how it's going to affect the real-life person out there.

Plainspoken And Blunt

During arguments, Sotomayor showed a knack for breaking down complex legal arguments and being blunt when necessary.

In arguing against the police powers under the Arizona law, Verrilli was floundering under questions from the justices on the court's conservative wing. He was unable to make his case in the way the chief justice wanted to hear it.

General, I'm terribly confused by your answer, Sotomayor said. And I don't know that you're focusing in on what I believe my colleagues are trying to get to.

Sotomayor then boiled down what exactly the conservative justices wanted from Verrilli, giving the government lawyer a chance to rebound.

Later, Sotomayor stated the obvious: You can see it's not selling very well, she told Verrilli. Why don't you try to come up with something else.

Agosto, the head of the Hispanic National Bar Association, said that was the kind of comment from the bench distinguishes her from the other justices.

No other judge said it as clearly as she did, he said. That's the most down-to-earth, real-life way of communicating.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.