Malaria Treatment Drug That Kills Parasite ‘In 48 Hours’ Shows Promise For Human Trials

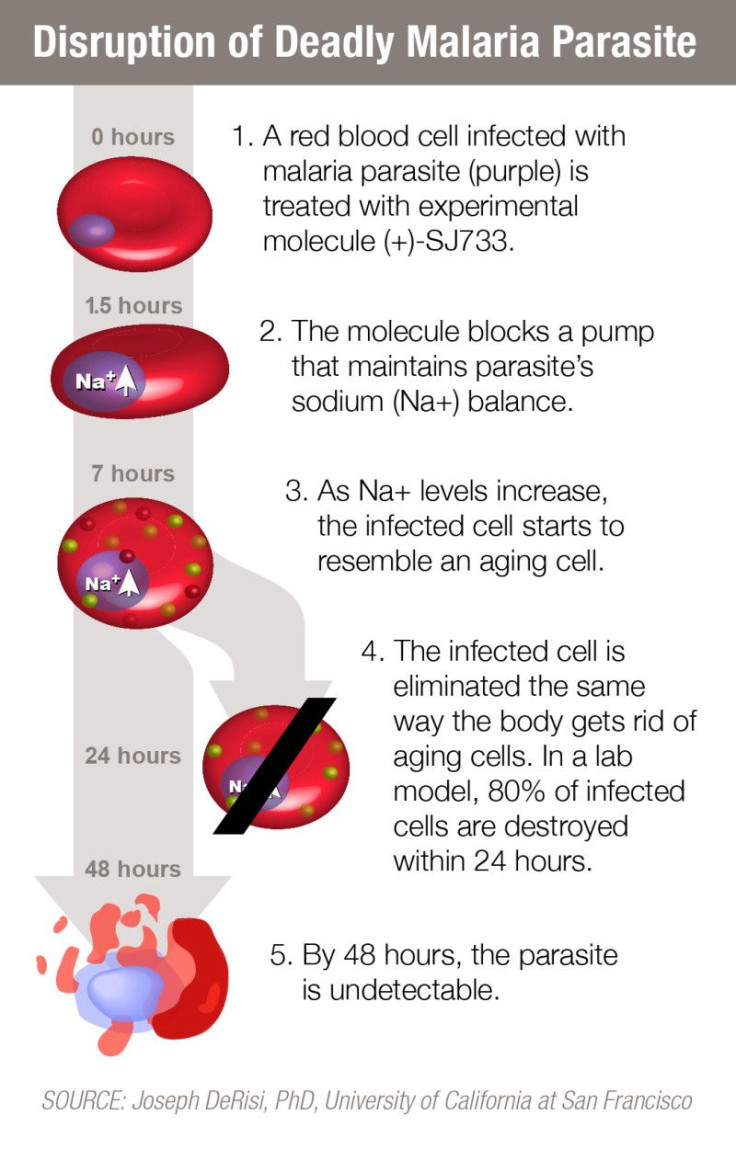

A new malaria drug that is said to kill 80 percent of the parasite in 24 hours and render the virus “undetectable” after 48 hours in mice shows promise for human trials, research from St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, indicates. The anti-malaria compound, known as SJ733, tricks the body’s immune system into flushing out red blood cells infected with malaria, a deadly disease caused by a parasite carried in the saliva of female mosquitoes.

The development of SJ733 comes at a time when world health officials are on the lookout for new approaches to treating the parasite, called Plasmodium, which experts fear is becoming increasingly drug-resistant. "Our goal is to develop an affordable, fast-acting combination therapy that cures malaria with a single dose," study author R. Kiplin Guy, who chairs the St. Jude Department of Chemical Biology and Therapeutics, said in a statement. "These results indicate that SJ733 and other compounds that act in a similar fashion are highly attractive additions to the global malaria eradication campaign, which would mean so much for the world's children.”

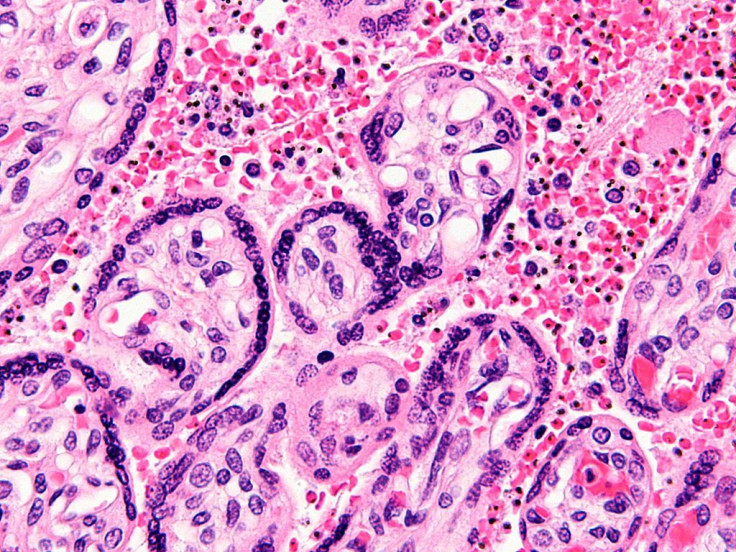

Researchers say SJ733 relies on the same mechanism the immune system uses to get rid of aging red blood cells. It targets a certain protein in the parasite called ATP4, which the parasite uses to maintain proper sodium balance. The treatment results in “rapid clearance” of infected cells while leaving uninfected ones “unharmed.”

There is currently no licensed vaccine for malaria. The parasite is transmitted to humans via mosquito bites and causes fever, headache, vomiting and chills, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

The disease infected an estimated 207 million people in 2012 and led to about 627,000 deaths; however, mortality rates have dropped globally by 42 percent since 2000 because of increased public awareness of the disease as well as better ways of detecting infection early on. More than half of the 103 countries with ongoing transmission of the disease 14 years ago are on track to reduce incident rates by 75 percent by next year, WHO reported. Most new infections occur in sub-Saharan Africa, south Asia and parts of South America.

Despite huge advances being made in the fight against malaria, the disease remains one of the leading causes of death and disease among children and pregnant women in affected areas. The majority of deadly cases in 2012 were among African children.

The cost of eliminating malaria entirely by 2020 is estimated to be about $5.9 billion a year, according to the Global Malaria Action Plan. That figure includes the “costs of prevention, treatment and control programs,” the group said.

Malaria drug development over the years has been mostly aimed at preventing infection, but health experts fear that widespread use of the type of anti-malaria drugs often taken by tourists to malaria-prone regions could have a resistance effect. Long-term use of malaria treatments has been linked to new and stronger outbreaks of the parasite. An experiment using malaria drugs on a larger scale in Tanzania in the 1950s showed an initial drop in the number of new infections, followed by a steep increase just five months later, according to a study published last year in the journal Nature. Similar problems arose in the Philippines in 2011 when malaria showed signs of resistance to the popular anti-malaria drug artemisinin.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.