Malaysia Airlines Flight Spotted In Maldives? Examining The Latest Theory On MH370

Update 8.30am ET: The Maldivian government issued a statement saying that the country's military and airport radars had not seen the flight. However, it should be noted that a large airplane, by flying at low level, could easily escape detection by radar.

According to a local newspaper, residents of a remote island in the Maldives, Kuda Huvadhoo, spotted a plane at 6:15 a.m. local time on March 8 that could have been the missing Malaysia Airlines 370. Eyewitnesses cited by the paper said they saw "a jumbo jet," white with red stripes across it, flying low and very loudly. The description of a big airplane in those colors is consistent with the Malaysian Boeing 777.

The islanders said they did not recall ever seeing an airplane there, and at that height, before, making it unlikely that what they had seen was a normal takeoff or landing by another passenger jet.

The time of the sighting also matches what we can deduct about the plane's range and its known whereabouts.

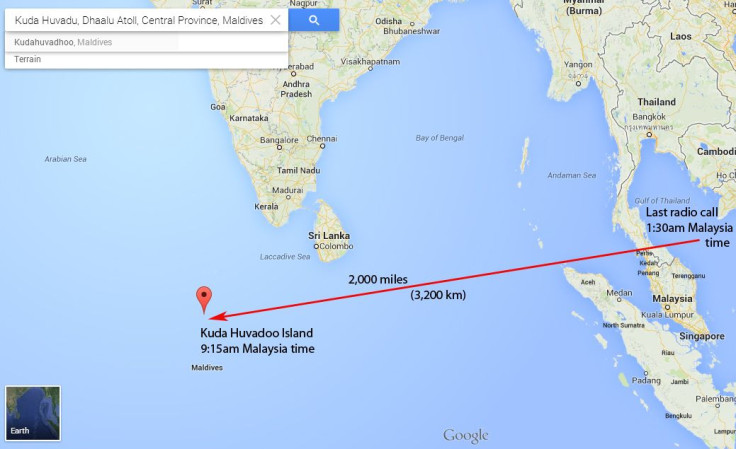

6:15 a.m. in the Maldives is 9:15 a.m. in Malaysia, so the sighting would have occurred seven hours and 45 minutes after the last radio contact, the now-famous "All right, goodnight" at 1:30 a.m. Malaysian time over the Gulf of Thailand.

A 777 series 200ER, with a nearly full load of 227 passengers and 12 crew, cargo, and fuel for the scheduled five and a half hour trip from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing, plus reserves, would typically be able to stay in the air for a maximum of about eight hours. That makes the presence of the aircraft at 6 in the morning local time in the middle of the northern Indian Ocean technically possible.

In fact, the distance between the point of last radio contact and Kuda Huvadhoo is 2,000 miles, which a 777 at cruise speed would cover in far less time. Flying in a straight line from the Gulf of Thailand, MH370 would have appeared over the island no later than 3 a.m. local time, well before sunrise.

But the plane may not have flown in a straight line, for whatever reason: possibly a hijacking, and maybe the crew's attempt to foil it. Or it may have flown at very low level to avoid detection, where the air is thicker and jet planes fly slower because of added drag. It may also have been flying at reduced speed to conserve fuel, either because whoever controlled the plane wanted to maximize its range, or because jet engines are less efficient at low altitude.

One thing the Maldivian eyewitnesses did not mention, at least in the local newspaper's account, is seeing signs of the onboard fire that some experts say could have incapacitated or killed the crew while the plane kept flying on autopilot.

The idea of a fire as cause for MH370 crashing was first floated by a pilot on Google Plus last weekend, and went viral. It rests on the assumption that the pilots, far from being in on some nefarious plot, were heroes who steered the plane toward the most convenient airport for an emergency landing as soon as they realized that they had a fire or some other grave problem.

That airport would have been on the island of Langkawi off the west coast of Malaysia, exactly on the compass heading that the plane took when it turned westward over the South China Sea. Then the crew succumbed to the fire, or to lack of oxygen, and the plane kept flying on autopilot until fuel ran out.

But the fire plus emergency diversion theory, as compelling as it is and similar to other known incidents, leaves one question unanswered. If the pilots tried for a landing at Langkawi and missed because they became incapacitated, the autopilot would have kept them flying straight and level on the last compass heading. (Which would have taken MH370 more or less over Kuda Huvadhoo, by the way.)

Yet we know from Malaysian military radar tracking that after passing the west coast of Malaysia, MH370 zigzagged north and west, toward the Andaman Islands, following precise waypoints. Shortly before reaching the Andamans, it was lost to radar, and might have possibly made the Maldives, before disappearing toward one of the two arcs -- one in Central Asia, the other off the west coast of Australia -- where satellite pings say it must have ended its flight.

So, either someone was entering those waypoints in the flight management computers, or the computers had been programmed earlier to send the plane there. The former option is not consistent with an unconscious or dead crew. The latter makes no sense for a crew in a dire emergency, looking for the closest place to land -- unless one wants to believe the improbable and now-debunked scenario that hackers were steering the plane.

If the Maldivian sighting is not a false lead, then, it lends strength to the theory that MH370 must have ditched or crashed in the ocean.

It did not land at the airport of the Maldives' capital Male, and the closest airport big enough for a 777, Mahe in the Seychelles Islands, 1,400 miles away, hasn't seen the missing jet, which could not have had enough fuel to get there anyway if it really overflew Kuda Huvadhoo when the eyewitnesses said it did. The U.S. and British airbase at Diego Garcia is closer, 800 miles away, and also has a runway long enough for the jet, but has not reported sighting the aircraft either.

As for the coast of Africa, lawless Somalia, an ideal place for a hijacked plane to land, is 2,000 miles from the Maldives. That would have been too far for Malaysian 370, and was also likely among the first places that spy satellites would have scoured for signs of a giant, easily visible airplane, which they did not see. And as Wednesday dawned in Malaysia, neither had anyone else, for the eleventh day since the mystery began.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.