Massive Japanese Tsunami Breaks Antarctic Iceberg [VIDEO]

NASA scientists were able to observe firsthand the powerful force of an earthquake as it calved off large icebergs a full hemisphere away from the epicenter.

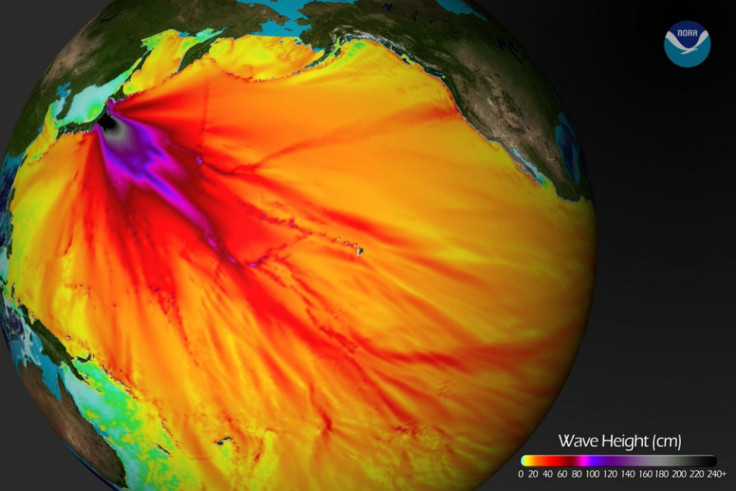

Specialists from the Goddard Space Flight Center were following the devastating Tsunami resulting from Japan's powerful earthquake last March as it rippled through the oceans towards the Sulzberger Ice Shelf in Antarctica near New Zealand.

Some 18 hours after the earthquake, the swells of water, traveling 8,000 miles, still had enough force to break off chunks of ice with twice the surface area of Manhattan.

The researchers were able to watch the Antarctic ice shelves in as close to real time as satellite imagery allows, and catch a glimpse of a new iceberg floating off into the Ross Sea.

"In the past we've had calving events where we've looked for the source. It's a reverse scenario -- we see a calving and we go looking for a source," said Kelly Brunt, a cryosphere specialist at Goddard Space Flight Center. "We knew right away this was one of the biggest events in recent history -- we knew there would be enough swell. And this time we had a source."

The swell was about a foot high when it reached the Sulzberger shelf, but the consistency of the waves created enough stress to knock the glacier off the shelf.

The Sulzberger shelf faces Sulzberger Bay and New Zealand.

Advanced satellite imaging, including the use of Europe's Envisat satellite which can penetrate clouds allowed for the discover to be witnessed as it happened.

Scientists have been speculating that waves could cause icebergs to break off ice shelves, but only with this observation has it ever been proven. The event also helps shed light on past events that as well, researchers said.

In September 1868, Chilean naval officers reported an unseasonal presence of large icebergs the Pacific Ocean. At the time it was theorized that it must have calved during the Arica earthquake a month earlier. The new findings make this the "most probable scenario," researchers said.

Douglas MacAyeal at University of Chicago said the event is more proof of the interconnectedness of Earth's systems.

"This is an example not only of the way in which events are connected across great ranges of oceanic distance, but also how events in one kind of Earth system, i.e., the plate tectonic system, can connect with another kind of seemingly unrelated event: the calving of icebergs from Antarctica's ice sheet," said MacAyeal.

Japan's powerful March 11, 2011 earthquake measured 9.0 on the Richter scale, killing over 20,000 people and causing an estimated $235 billion in damages, according to the World Bank.

The resulting tsunami also destroyed Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO)'s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Fukushima prefecture, making it the worst nuclear disaster since the Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster of 1986 in North Ukraine.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.