McKinney Pool Party Video Update: Texas City's Residents Say They Are Segregated By Economic Class, Race

Chanelle Yarber lives in a quiet subdivision on the more affluent side of McKinney, Texas. But customers who saw her ringing purchases as a minimum wage, part-time sales associate at the local Target two years ago might not have placed her on the city’s upscale west side because of her skin color, she says.

Most of her former co-workers were from the poorer, less maintained part of town -- the side with a large concentration of low-income African-Americans and Hispanics. Yarber, who is black and now works as an independent Internet marketer, said she was reminded of the disdainful glares she received from Target customers when she read about how a few McKinney adults insulted a group of black teenagers attending a pool party on the west side last week, prompting a violent response from white police officers that quickly made national headlines.

“When the lady [at the pool] said go back to your Section 8 housing, I’m assuming she thought the kids were from the east side,” Yarber, 31, said in a phone interview. “But it’s highly unlikely that those kids were from the east side. Those kids would not be going to school with people who had permission to swim in that pool if they didn’t live on the west side.”

For Yarber and other residents of McKinney, the fallout from the police response to an end-of-the-school-year celebration last Friday was a reminder of the community’s growing struggles with issues of class and race. Newer residents said they moved to McKinney because of its growing diversity, good schools and proximity to a major economic and job center. But some described a city increasingly divided by race, class, income and ethnicity issues, where the color of a person's skin and what side of town they live on can define relationships and opportunities.

“It’s kind of like they’ve divided us up, in a way,” Yarber said. “Maybe this [pool party] event just needed to happen, to make us see.”

A Great Place To Live

On Yarber’s street in the Sandy Glen residential subdivision, she has white, Hispanic, black and Middle Eastern neighbors. She’s called the area home for seven years. Many of the homes are two- to three-bedrooms with front lawns and backyard patios. Yarber’s mother enjoys early morning walks around in their cul-de-sac. The neighborhood gets together occasionally for block parties.

“I go next door to my Guatemalan neighbors’ house all the time,” Yarber said. “I eat their food, and they teach me Spanish.”

A highway divides east and west McKinney, and the west side enjoys easier access to Target, Best Buy, Home Depot and gourmet supermarkets. Yarber says there’s almost nothing like it on the east side.

The oldest, more historic areas of McKinney are located on the east side, while most of the residential and commercial development has been concentrated on the west. Anna Clark, the city spokeswoman for McKinney, said officials regularly use the downtown square area and parks on the east side for city-sponsored recreational and cultural events.

A Hawaiian night event and Juneteenth -- the annual remembrance of the day American slaves in Texas learned they were free -- celebrations have been sponsored in recent years. This year, however, Clark confirmed that an event for Juneteenth has not been planned for next week, when it is typically celebrated nationally. She was uncertain about why it hadn't been planned this year.

McKinney was previously recognized as one of fastest-growing cities in the U.S., each year from 2000 to 2003 and in 2006. The growth was driven largely by out-of-state transplants and migrations from other parts of Texas, according to a state demographer. Money magazine chose McKinney as the No. 1 place to live in the U.S. last year.

These days, McKinney, located northeast of the Dallas-Fort Worth area, has a population of more than 148,000 people, up from 54,000 residents in 2000. In 2010, the city was 64.5 percent white, 10.5 percent black and 18.6 percent Latino, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. It was nearly 80 percent white just 15 years ago.

McKinney residents are generally more financially secure than most people in the country. The city had an estimated median income of $81,118 in 2013, and 46 percent of residents age 25 and older had at least a bachelor’s degree. The median income in the U.S. was an estimated $52,250 in 2013.

But there’s a drastically different reality for people who live west or east of Sam Johnson Highway -- named after the former Republican congressman and U.S. Air Force officer -- which runs north and south through the center of McKinney. On the predominantly white and more affluent west side, the median household income was $98,524 in 2013, with whites earning an average $100,180. Blacks who lived there averaged $86,108 and Hispanics averaged $64,318.

On the east side of the highway, where blacks and Hispanics are more heavily concentrated, the median household income drops to $45,907. White people on the east side earned an average $47,845 in 2013, while black and Hispanic people earned $27,500 and $33,860, respectively.

Residents interviewed since the pool party video controversy have said that they chose McKinney because of its good schools. McKinney Independent School District, which has 31 schools, including three high schools, is rated by the Texas Education Agency as “academically acceptable.” The only school rated as unacceptable, McKinney High School, is located on the east side.

All members of the seven-seat city council, including the mayor, are white and male. There are 83,118 registered voters in McKinney. About 5.8 percent of voters turned out for a municipal election last month and 65.8 percent cast ballots in the 2012 presidential election, according to Sharon Rowe, the elections administrator for Collin County. The county encompasses McKinney and about 32 other communities. Sixty-five percent of Collin County voted for former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney in 2012.

'They Are Trying To Divide People'

John Greer, a 42-year-old white McKinney resident since 2010, lives in a "higher end" home on the east side. A married realtor, Greer was elected in 2012 as a precinct chair for the local Republican Party. He doesn't completely agree that McKinney has a race or class problem.

"There is more crime, probably, in the lower [east side] neighborhoods," Greer said in a phone interview. "But I wouldn’t say that it is white versus black, or anything like that. As involved as I get, I’m kind of tired of the labeling that the media and the government puts on people. I think they are trying to divide people and cause these race issues."

Greer said too many people have made the pool party incident about race, when there is a lot of agreement between whites and blacks that the police response was wrong. "I wish people would say, 'This is how an adult is treating this child,' " he said. "And other adults are assisting in the assault of those children. [The police] work for us, obviously, so they need to respect all the people they work for."

The Craig Ranch North Community Pool is part of a large, upscale subdivision with a centrally located town center and shopping district. It’s where the African-American teens attended the pool party.

While some of the black and white teens at last Friday’s pool party had guest passes to swim in the facility, others reportedly climbed over the gate that encloses the pool, angering some of its white patrons who assumed they were not from that part of town. Racially-charged insults were reportedly hurled at the black teens, sparking physical altercations between a few white adults and a teenage party organizer. A witness summoned police to the scene.

Brandon Brooks, a white teenager attending the party, recorded the police response. The now-viral video, posted Saturday to YouTube, shows McKinney Police Officer Eric Casebolt shoving, cursing and drawing his service weapon on black teens near the pool. He also wrestled a 14-year-old girl in a bathing suit to the ground.

Casebolt resigned from the police department Tuesday and issued an apology to the community through his attorney. An investigation into the incident was still underway, McKinney police Chief Greg Conley said.

Elected officials in McKinney did not immediately respond an interview request for this story on Thursday, but leaders sought to isolate the pool party incident from the city norm.

“I have received many emails and phone calls, and it is important to point out that while Friday’s incident demanded and received our fullest attention, it is not indicative of McKinney as a whole,” McKinney Mayor Brian Loughmiller said in a statement released earlier this week. “We have good, law-abiding citizens throughout our community including in our Craig Ranch community, and we have good public servants in our police and fire departments. The actions of any one individual do not define us as a community.”

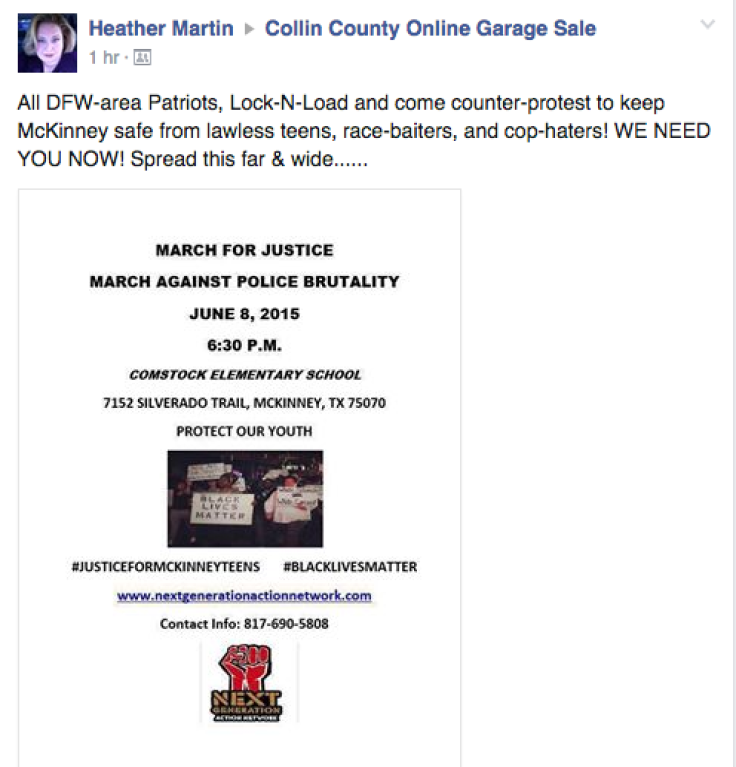

Hundreds protested Monday in McKinney, calling for an end to police brutality. The protests mirrored the vein of anti-police protests that have been seen around the country in the past year. Yarber said there were some pro-police counter protests, but they were grossly outnumbered.

'African-American Residents Shouldn’t Be Here'

Therasa Thomas is a 41-year-old, black McKinney mother of two teenage sons, including one whom she dropped off at the pool party. Thomas, director of education for a national nonprofit agency, said she and her husband didn’t hear about Casebolt’s conduct until the following day. They were shocked and then relieved that the officer didn’t hurt their son or anyone else at the pool.

But the behavior of the white adults at the pool did not shock the Thomas’ at all. “There are some attitudes that African-American residents shouldn’t be here,” she said. “That’s typical of an area like this, as it becomes more diverse. I think it is a racial thing and a human thing. They are just resistant to change.”

Thomas, who has lived in the city for six years, pointed to McKinney's being pushed into building more low-income and affordable housing on the west side a few years back. The Inclusive Communities Project, a Dallas housing and civil rights advocacy organization, brought actions against the city of McKinney and the McKinney Housing Authority on Aug. 18, 2009, after officials rejected a proposal to construct the Section 8 housing on the west side.

The city eventually settled with ICP, agreeing to provide loans to developers for the construction of as many as 400 low-income housing units. The units would serve a growing number of African-American and Hispanic recipients of Section 8 public housing vouchers. Since that settlement, an application sponsored by ICP and the McKinney Housing Authority received tax credits for a 164 unit development on the west side of McKinney in 2013, said Daniel & Beshara, P.C., the law firm that filed the suit on ICP’s behalf. Last year, the McKinney City Council passed a resolution supporting a second low-income housing project on the west side.

“That’s because of the law and not because of the goodwill of the people,” Thomas opined. “So let’s not kid ourselves. This is why you need diversity. The city officials [making those decisions] should reflect the entire community.”

Thomas said she’s concerned that the local schools don’t take cultural diversity seriously enough. Black History Month can seem like an afterthought, and her sons have encountered racism at their schools -- such as racial slurs. “That to me is a larger problem," she said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.