As Mexico's Sugary Drink Tax Turns 1 Year Old, US Health Proponents Hope It Can Sway American Voters

Mexicans are guzzling fewer sodas, juices and flavored waters since a nationwide sugary drink tax took effect in 2014. The policy aims to help curb rising rates of obesity and diabetes in Mexico, which recently overtook the U.S. as the world’s fattest country. Now public health proponents north of the border say they’re hoping Mexico’s positive start can sway U.S. voters to adopt similar taxes.

“If it’s shown that Mexico’s soft drink tax is effective in reducing soda consumption, and that in turn has an effect on Mexico’s obesity rate, I think you’ve got a pretty good case,” said Michael Roberts, executive director of UCLA’s Resnick Program for Food Law and Policy.

In both nations, epidemics of weight gain and associated diseases can be tied partly to the soaring consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, which has more than doubled in the U.S. and Mexico in recent decades. About half of all Americans drink soft drinks daily while Mexicans as a whole drink the equivalent of 3.6 million cans of Coca-Cola each day.

“I usually have two soft drinks a week, and maybe a juice. But I have friends who drink a liter of Coke every day with their meal,” said Victor Yerves, 31, a journalist in Mexico City. On a recent evening in Tulum, a Caribbean beach town, customers at streetside taco stands explained they usually enjoy a soda with every lunch and dinner. Plain water, they said, is rarely the preferred option.

Proponents of taxes on sugary drinks, including public health researchers, say raising the price of sweetened beverages is an effective way to reduce consumption and, in turn, lower health risks. Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto approved the action in October 2013 after years of interest from national health experts, who saw the tax as one antidote to Mexico’s alarming diabetes rates. As many as 10 million Mexicans have diabetes, or roughly one-sixth of the adult population, according to government data. Nearly a half-million people died from diabetes from 2006 to 2012, a rise of nearly 60 percent from the previous six-year period.

“In Mexico’s case there’s no alternative but to have a tax. We have a crisis,” said Alejandro Calvillo, director of Consumer Power, the Mexican advocacy group that led the beverage tax campaign in Mexico. The measure, which took effect Jan. 1, 2014, adds 1 peso (about 7 cents) to the price of a liter of sugary refreshment.

A year later, preliminary data suggest consumption rates are falling, though it’s too early to say precisely how much, said Barry Popkin, who teaches global nutrition at the University of North Carolina in Raleigh and is working with Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health to study the country’s soda tax.

The institute's earliest results suggest in the first three months of 2014, purchases of sugary drinks dropped by 10 percent from the same period in 2013. “The results were pretty positive. In essence there was a reduction in sugary beverage intake, and there was some increase in healthier drinks, like water,” Popkin said. Researchers should have more conclusive 2014 results on both consumption levels and related health impacts within a few months, he added.

In the meantime, there’s the corporate data. Coca-Cola Femsa, Mexico’s biggest soft drink bottler, saw its drink sales drop by 6.4 percent in the first half of last year, compared to the same period in 2013, in part due to the drink tax and other economic factors. Another Mexican Coke bottler, Arca-Continental, said its drink sales slipped by 4.7 percent in Mexico for the same period. And more than half of Mexicans last year said they had lowered their sugary drink intake compared to 2013, according to an August survey.

The reductions aren’t only a function of higher beverage prices. Like taxes on cigarettes and alcohol, the measure itself signals to consumers highly sweetened refreshments are a vice, Calvillo said. “People are becoming more aware about the risks of sugary drinks,” he said. For example, parents are serving less sugary juice and soda to their young children. Schools are pushing plain water in the classrooms, and Mexicans overall are opting for lower-fat milk.

Gaby Chavaro of Mexico City said she recently noticed a change in the dietary habits of her friends and family. “It’s not so much because of the prices, but because we’re more thoughtful about what we eat,” she said. “We’re more concerned about our health … and are trying as much as we can to stop eating processed foods.”

Mexico’s drink tax is inspiring similar efforts in Chile, Ecuador and Peru, where soft drinks are ubiquitous in the average household. But in the United States, the notion of taxing liquid sweets remains anathema to many residents, despite the country’s troubling obesity rates. Roughly two in three American adults are overweight or obese while more than 29 million people, or 9.3 percent of the country, are diabetic, U.S. government data show.

“Diabetes and obesity are wreaking havoc on public health in this country. It’s a personal and economic disaster,” said Roberta Friedman, director of public policy for the Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity at the University of Connecticut. She said that sugary drink taxes are a “good public health measure” to confront the problem.

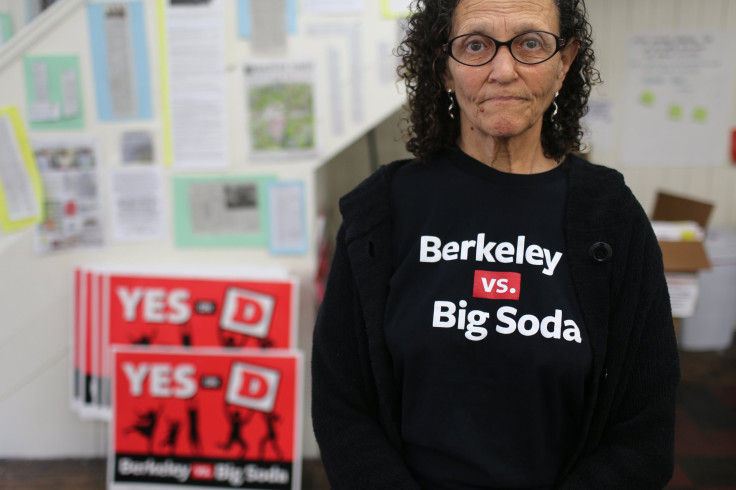

U.S. voters, however, have rejected more than 30 efforts by various cities and states to implement a soda tax, including most recently in San Francisco. Only one city has succeeded so far: Berkeley, California. The small liberal enclave adopted a 1-cent-per-ounce tax in November after an aggressive fight between beverage companies and consumer rights groups, the latter of which received some $650,000 in support from Bloomberg Philanthropies, an initiative of former New York City mayor and public health advocate Michael R. Bloomberg. (His philanthropic arm also gave Mexico a $10 million, three-year grant to tackle obesity and promote the drink tax effort.)

Popkin said that part of the reason tax proposals have failed in the U.S. is that Americans tend to view public health problems like weight gain as an individual challenge, something that people must overcome on their own. Latin American leaders, by contrast, have a more collectivist mindset -- the obesity problem is society’s problem. Roberts pointed to America’s “cultural resistance to tax as a public policy tool” as another key difference among the countries.

The beverage industry contends that taxes haven’t gained ground because Americans know they’re a bad idea.

Chris Gindlesperger, a spokesman for the American Beverage Association, a national trade organization, said sugary drink taxes are “discriminatory and regressive” because they punish low-income families the most, since those consumers spend a greater percentage of their income on grocery bills than wealthier families. And indeed in Tulum, Mexico, where patrons gathered at taco stands, some complained that in paying more for soft drinks, people had less money for their daily budgets. “With these prices, there’s not enough money for other things,” one man complained.

Gindlesperger also disputed that taxing beverages could improve people’s health, pointing to the industry’s own initiative to offer low- or no-calorie products as a more effective alternative to drink taxes. Beverage companies in September set a goal to reduce each person’s drink calories by 20 percent by 2025, in part by providing smaller portion sizes and healthier bottled options.

“Together we can get much further than by singling out an industry and trying to demonize them,” he said.

Yet even without drink taxes, American attitudes toward junk food and sugar-rich drinks already may be changing. Nearly two-thirds of Americans said they avoid soda in their diet while more than half said they avoid sugar, a July Gallup poll indicated.

“Everyone knows someone who struggles with weight. The problem is not disappearing,” Roberts said. “That will continue to put pressure on our society to come up with a solution.”

Correction 1/13/15: An earlier version of this story said that one in six Mexicans suffer from diabetes. The correct figure is one in six Mexican adults.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.