MH370 Vanished - And We May Never Know Why

At midnight March 7, the passengers of MH370 lined up at their gate at Kuala Lumpur International Airport to board their flight to Beijing. At that time of the night in Malaysia, the moon could be seen setting in a clear sky; the conditions were perfect for flying. Malaysia Airlines agents had everyone seated ready for takeoff just 30 minutes later. It would be a six hour, 22 minute flight. But the plane never made it to China. At 1:30 a.m. March 8, the plane disappeared from radar screens and fell out of communication with air traffic control.

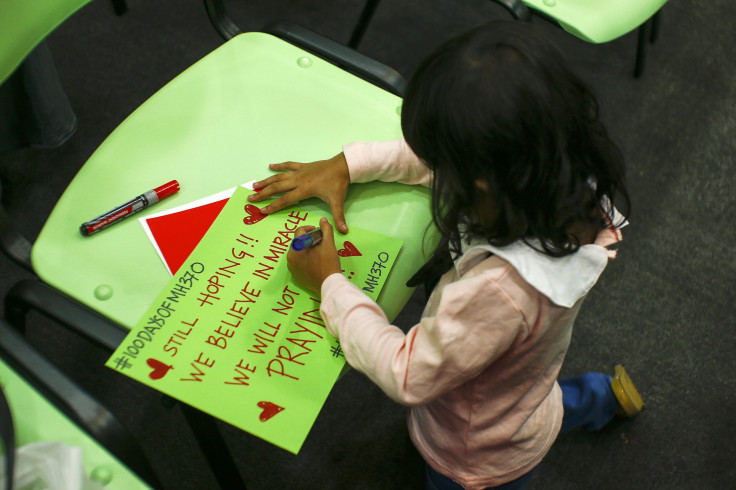

Now, 100 days later, despite tens of millions of dollars spent and efforts by 14 countries, 43 ships, 58 aircraft (and requests for radar information from as many as 26 countries), the plane is still missing along with the 239 people who were aboard. Investigators admit they do not know where the plane is. Given the time spent looking and the lack of answers, the MH370 families -- and the rest of us -- may have to deal with the idea we simply never will know what happened.

In a world that is increasingly defined by an overload of data, the prospect of permanent ignorance is hard to accept.

Details of how, when and where the plane disappeared have changed dozens of times, confusing and angering the families of the passengers. For weeks, they held on to the hope that their sons, daughters, fathers, mothers, sisters and brothers were alive. Some thought they were fighting for their lives somewhere against, perhaps, hostage-takers; others hoped the passengers had made their way to land. They are still waiting for answers.

“The biggest challenge that we faced was … the huge uncertainty in the splash point. You had a huge area to search,” said Susan Wijffels of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO), Australia's national science agency. CSIRO provided authorities with information about the currents and swells in the piece of the southern Indian ocean marked off as the most likely search area after it became clear the Boeing 777 was not to be found along or near the path from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing.

In the hours following the flight’s disappearance, a multinational search effort began in the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea. Military radar suggested the plane had diverted off its original course, and taken an easterly course over the Malay Peninsula, ultimately disappearing over the Indian Ocean. The reasons behind the sudden radio silence followed by diversion and disappearance are still unclear. Speculation ranges from pilot suicide to a hijacking to an onboard fire that caused systems to collapse. But in the absence of hard data, the mystery remains near-absolute.

The plane’s black box, investigators thought, would give them answers once located. But 30 days later, when the black box batteries died and with them the hope of intercepting their locator beacon signal, investigators still had no leads.

Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak said in a statement March 24 a data analysis performed by British specialists showed the flight had gone down in the Southern Indian Ocean, and none of the passengers could have survived. A new search began off the coast of Australia, but at the end of April, Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott announced the search would be called off until further notice.

In the meantime, Australia is working with the Malaysian government, the main driver of the investigation, to develop a plan to continue the search. Hishamuddin Hussein, Malaysia's transport minister, insists his government will stay committed: "One hundred days after MH370 went missing, its loss remains a painful void in the hearts of all Malaysians and those around the world," he said in a statement. "We cannot and will not rest until MH370 is found."

While past efforts have relied on government resources, the future of the search could lie in the hands of a private company.

The Australian Transport and Safety Bureau (ATSB) announced June 6 it still maintains the aircraft went down somewhere in the Indian Ocean, which is 28.4 million square miles (73.56 million square kilometers).

ATSB called for private companies to apply to provide the equipment needed to search the ocean’s floor. A statement released by the bureau June 4 said the company winning the bid will aim to “localize, positively identify and map the debris field of MH370” with specialized equipment such as underwater vehicles using sonar and cameras. But that, Australia warned, may take a year.

Documents released by ATSB identify a specific timeline for the chosen company to follow, and requires it search an area as large as 60,000 square kilometers. The announcement came after an Australian and U.S. Navy search using the unmanned sub Bluefin-21 failed to find any sign of the missing aircraft.

Robert McCallum, vice president of Williamson and Associates, a geophysical consulting firm based in Seattle, said the company had applied for the tender position with ATSB. Williamson and Associates specializes in sonar equipment that helped find an Australian warship HMAS Sydney in 2008, more than 60 years after it sank to the bottom of the Indian Ocean in World War II.

If sonar equipment does not detect the wreckage on the ocean floor, the Malaysian and Australian governments have few options -- other than waiting for wreckage to wash up somewhere. Investigators in previous plane crashes have relied on physical evidence making its way to the surface of the ocean, or for pieces of the plane or bodies to wash up on coastlines.

It is essential the authorities know the currents of the search area to better understand where debris may have shifted, Wijffels said. CSIRO has used what are known as Argo Floats -- free-drifting profiling floats dropped into the ocean -- to gather information about temperature, currents and swells.

CSIRO also dropped thousands of artificial drifters that were meant to represent different parts of plane debris in the search area to understand how the ocean would hypothetically move the material.

The winds in that area of the ocean blow north past Australia and then very quickly toward Africa, Wijffels said, but pass through quiet zones that tend to collect debris, particularly garbage.

And even finding pieces isn't synonymous with finding answers.

“Each failure mode has its own fingerprint, so you are a detective trying to look at different pieces,” said Craig Jerner, a metallurgical engineer who has assisted as an expert on previous crashes. “The very difficult thing here is that even if they can recover it, they have to put Humpty back together again.”

Such was the case with Air France Flight 447, which crashed into the Atlantic June 1, 2009, and TWA Flight 800, which went down into the ocean off the coast of Long Island July 17, 1996. Once the investigators gathered the physical evidence, both debris and bodies, they began to piece together explanations that answered the same questions that MH370 relatives are asking.

But right now, we are nowhere near that stage. Three months after the Boeing 777 failed to arrive in Beijing, there is nothing with which to work. As incredible as it still sounds, a jumbo jet and 239 people simply vanished.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.