In Moscow, Ukraine War Worries On The Mind As Russia Celebrates World War 2 Victory

MOSCOW -- On Friday, Russia, along with most of the nations that used to make up the Soviet Union, stops for a holiday that remembers its bloodiest war. May 9 is Victory Day, the celebration of the victorious campaign against Nazi Germany which ended with the enemy’s unconditional surrender, on that date 69 years ago. The Soviet Union had paid for its victory with 20 million dead.

As Russians stop to remember that war, they are concerned about a possible new one. According to the latest poll conducted by the Levada Center, an independent pollster, 77 percent of Russians are "concerned" about the possible outbreak of a military conflict with Ukraine, up from 66 percent in March.

While President Vladimir Putin has backed away from his aggressive statements regarding Ukraine, even asking pro-Russian separatists in the country’s east to postpone a planned Sunday referendum on autonomy, the fear of a war is echoed in Russia’s media.

Ironically, Russians and Ukrainians were united in the struggle that is being commemorated Friday: the Red Army included both nationalities, as well as all the Soviet Union’s other components. And for the first time this year, the traditional air parade over Moscow will be accompanied by a similar event in Crimea, to mark both Victory Day and the peninsula’s unilateral incorporation into Russian territory from Ukraine, Defense Ministry Sergey Shoigu said this week.

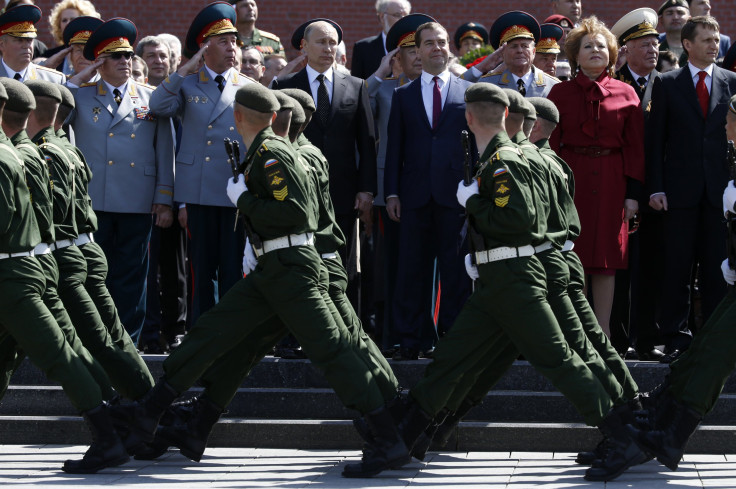

In Moscow, soldiers, tanks, missiles and armored vehicles will parade in front of the Kremlin like every year since 1945, while the air force’s jets and attack helicopters fly overhead. Putin, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev and senior government officials will attend, as Soviet leaders did in the old days.

Authorities are touchy on the subject of whether the hardware they are parading in Red Square would ever be used in anger against Ukraine. This week, a Defense Ministry official asked a popular independent-leaning online newspaper to change a banner that read "On the Edge of War" and showed Russian military planes.

It was not strictly censorship, since the official wasn’t complaining about the paper’s reporting, but he did ask to “please find something neutral for illustration purposes.” A journalist who works at the website and asked to remain anonymous said the site complied, although it could be debated whether the replacement image, depicting Russian tanks, was a lot more peaceful.

The government can be even heavier-handed than that in dealing with the mainstream Russian media. A star reporter at the Izvestia daily, who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons, recently complained to his colleagues that his editor told him "we need propaganda now." He decided to quit in response, but said he was alone in doing so.

This week, medals for “balanced” reporting were awarded by the Kremlin to more than 300 journalists, including the head of the English-language RT television, Margarita Symonyan. Her channel was labeled as a “propaganda bullhorn” by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry.

That "balanced" reporting isn’t winning the trust of many ordinary Russians, who believe they have been deceived. "It looks too rosy on television now. It will be good to hear the other side," said Elena Lukyanova, an accounting manager from Irkutsk, in Siberia, who was in Moscow to watch the Victory Day celebrations.

A virtual war over Ukraine is already going on among Russians on social networks, as they unfriend and call each other names over a possible real conflict.

One Facebook user, Alexander Latishev, an official in one of the Moscow city’s district offices, wrote on his page on Monday that "it is time to send troops to Novorossiya," referring to eastern and southern Ukraine by its Tsarist name of “New Russia” (a name that, incidentally, Putin himself used in a televised press conference in March.) Some of his friends dissented, but he was undeterred. The region should "be taken over" like Crimea to save pro-Russian people, wrote Latishev: "If we won't take them, pregnant women will be strangled not only in Odessa, but in Sevastopol [Crimea]."

He was referring to the strangling of a pregnant woman, a cleaning lady at Odessa’s Trade Unions Building, allegedly killed by Ukrainian nationalists during a deadly clash with pro-Russian separatists last Friday. The episode was reported by some Russian media and in some social networks, but an investigation by Radio Free Europe’s Russian service found there was no evidence that it ever happened. Doctors said they had never seen her among the dead.

Still, more than 40 people died in the building after it was set on fire by a Molotov cocktail, a tragedy that has touched Russians. Many wept while laying flowers at a memorial near the Ukrainian Embassy in Moscow this week. “Those fascists are not humans,” one man who was laying flowers said.

Liberal Russian journalist Andrey Pertsev was also shocked by events in Ukraine, but he pointed out another episode that implicated pro-Russians in eastern Ukraine: the interrogation of captured, wounded Ukrainian officers by separatists who humiliated them. "This is terrorism. They did it under my country’s flag with a St. George ribbon," he said. The officers were later exchanged for pro-Russian separatist Dmitry Gubarev.

The ribbon itself is an embodiment of the conflict among Russians over the situation in eastern Ukraine. Once a symbol commemorating World War II, the orange and black ribbon of St. George has turned into a symbol of support for pro-Russian separatists, who use it to identify like-minded people. Because of this newfound association, some people are now refusing to wear it to commemorate Victory Day.

Victoria Voloshina, an opinion writer at Gazeta.ru, said she had noticed fewer ribbons on cars this year. The ribbon controversy, she wrote, was an example of division in Russia, among people “who refuse recognize the patriotism of others who think differently.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.