'Mummies' Brings Dead Back To Life At Natural History Museum: Learn About Mummification Process

Birth and death are the two things that every single person has in common. And the way science is going, it may soon only be the latter. What happens to our bodies after we die, however, is less uniform. Different cultures past and present view death and treat the dead differently. Learning about those distinct customs can tell you a lot about a society.

That’s part of what makes the upcoming “Mummies” exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City so fascinating. The details of how bodies were preserved are a glimpse into how death was celebrated in ancient Egyptian and Peruvian societies, and it’s information that’s ironically on display in one of the nations where death is often considered a scary or taboo subject.

The exhibit, which has traveled to New York from Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, includes artifacts that haven’t been seen publicly in more than 100 years, NYC museum President Ellen Futter said during a preview of the exhibit for the media on March 16. Before leading everyone inside, as a titanosaur skeleton’s elegantly long tail swept above the crowd and cast eerie shadows on the black walls, she explained that advancements in technology have allowed researchers to view mummies in great detail without unwrapping and potentially degrading them.

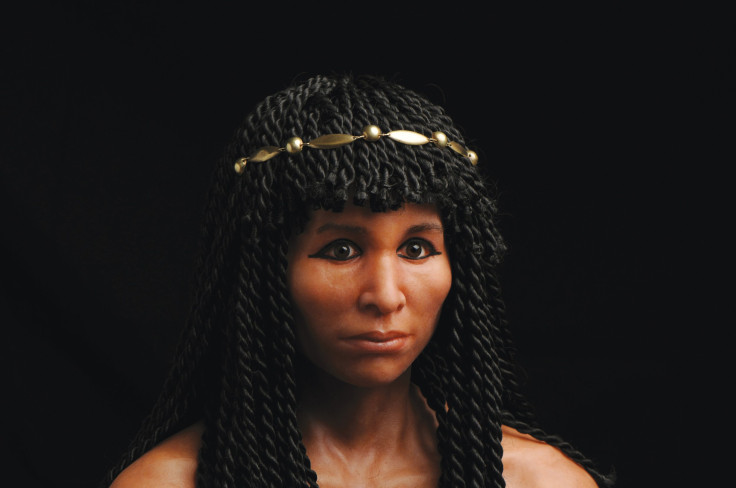

Indeed, one element of the exhibit was the end product of a process that started with CT scans of a mummy, went to a virtual reconstruction of the mummy’s skull, later carved out that reconstruction with a 3D printer, and then used the model skull to create a bust of a woman with brown skin, dark ropes of hair, wide eyes and full lips — an estimation of what she looked like before she died. And an interactive table in the exhibit allows the user to pick apart a mummy piece by piece, zooming in or changing the angle to get a better look. One of the interactive mummies is the same woman whose bust is on display: the so-called Gilded Lady, who was mummified during the period in Egypt when it was under Roman rule, between 30 BC and AD 395. As you peel away the layers of her encasement, you can turn her on her side to get a good look at swirl impressions on her head that denote her curly hair.

All of the inhabited continents have seen at least one culture that practiced mummification, AMNH curator David Thomas said, and it was about there being “something bigger for their dead.” In the case of the Egyptians, they were preparing their comrades for the afterlife. In Peru, mummification allowed the living to stay connected to those they had lost.

In addition to information about the mummification process, “Mummies” includes details about how the preserved people were buried. In Peru, they could have been placed in a pit in the ground, surrounded by containers with a corn beer called chicha and dishes of fish, beans, corn and spices. The Peruvian dead on display were wrapped in cloth bundles that were secured with rope — a modest sendoff compared to the elaborately decorated coffin, called a sarcophagus, for which ancient Egypt has become known.

The exhibit will open to the general public starting March 20 and stay open through the beginning of 2018.

See also:

Ancient Skull Tells How Humans and Neanderthals Evolved

DNA Links the Same Aboriginal People to Australia for 50,000 Years

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.