Musicians And Songwriters Are Fed Up With Low Royalties -- And They Are Starting To Organize

WASHINGTON -- After years of hanging their heads or sitting on the sidelines as disruptive digital forces chipped away at the music industry’s bottom line, working-class musicians and songwriters are starting to embrace the power of banding together and agitating for change, whether it’s engaging lawmakers to influence policy or joining coalitions that will fight for their interests. At the Future of Music Coaltion’s 15th annual Music Policy Summit here, the unofficial theme that emerged was a need to organize and rally to bring about real changes in the way musicians and songwriters are compensated in an evolving industry.

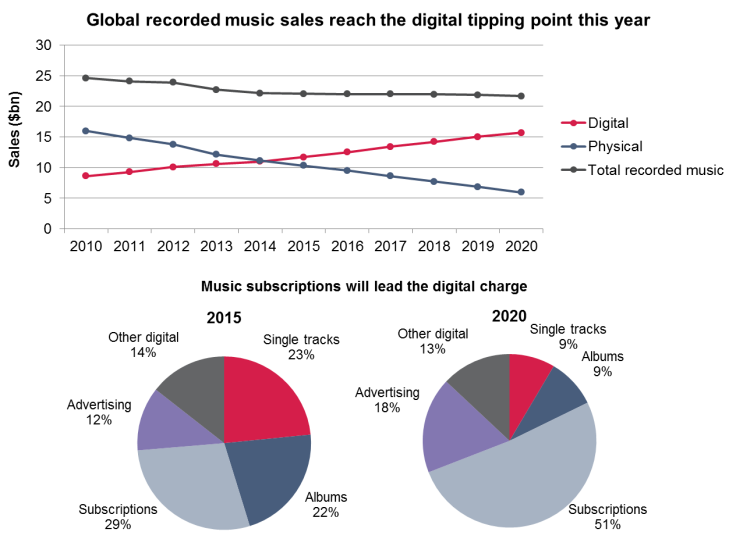

“We're at a tipping point right now,” Kevin Erickson, communications manager at the Future of Music Coalition, said. “People are moving past defeatism and starting to recognize the power of communicating authentically.”

Evidence of the movement is everywhere. One year after the Recording Academy, the trade body in charge of the Grammys, sent 107 registrants out to local congressional districts as part of an initiative called Grammys in My District, the organization rallied 1,650 registrants this month. Less than two years into its existence, the Content Creators Coalition has established local organizing chapters in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago and Nashville. And Rick Carnes, president of the Songwriters Guild of America, intimated Monday that his organization is about to launch a global ad campaign that will call for a rethinking of how people pay for music.

That shift in consciousness, more than a decade in the making, is far from complete. While many prominent legacy artists have begun to raise their voices on issues including a performance royalty for radio and the split of compensation between songwriters and performers on streams, not everybody is buying in. Discussions about forming an artist-serving pressure group at closed-door meetings organized by the Music Managers Forum across the United States this month often turned contentious, and aside from the odd Taylor Swift editorial, few of the biggest names in popular music have become vocal.

“Telling the truth is kind of a radical act right now,” Erickson said

But in the wake of some conversations taking place here, attendees at this week’s summit hope that could soon change.

An Uncomfortable Workforce

That musicians face economic challenges is not news to them. Music-making has never been an easy way to make money, and one of the conference’s most frequently cited statistics illustrated that today it is especially hard: The average musician in the United States makes less than $20,000 per year, well below even the 10 worst-paying jobs in America. That number wound up conflicting with some separate data the FMC unveiled Tuesday, but it was enough to get attendees to sit up straight in their chairs.

“Nobody can live on that,” said Andy Schwartz, an executive board member of the American Federation of Musicians' Local 802 chapter.

But despite the fact that they all fit into two Bureau of Labor Statistics categorizations, musicians are a varied professional class with a diverse array of interests: The concerns of a session musician in Los Angeles, for instance, differ drastically from those of a second-line player in New Orleans, which in turn have little to do with the priorities of a teenage band that's just gotten its first album accepted onto Pandora, and so on.

The factional nature of the music business, along with a lack of comfort with the issues and an unwillingness among musicians to fight for what they’re owed, has contributed to the silence from many stakeholders.

“We need to embrace a different attitude about our role as musicians,” Schwartz said. “Whether it's a record company, a club, a larger venue, a record label, a film producer, a TV producer -- they're looking at us as labor.”

“There's differences in the artists' population,” Erickson said. “But at the same time, there's so much common ground.”

This newfound momentum may be related to a number of factors, and a shift in how music is consumed is chief among them. It is finally becoming clear that music consumers around the world would rather access music than purchase it. According to research published Wednesday by Ovum, more than half of the recording industry's income will come from subscription streaming services by 2020.

That shift has been traumatic for artists and musicians, who for a whole host of issues -- including a lack of transparency, administrative problems and royalty rates negotiated without their input -- have seen their incomes negatively affected by the transition.

The sudden push to rally songwriters to change this state of affairs has some urgency to it. The Songwriters Equity Act and the Fair Play, Fair Pay Act -- two bills recently introduced to Congress -- would each make enormous changes to the way that performers and songwriters were compensated for their work. The former would revise how much songwriters were paid for the use of their compositions, and the latter would see performers earn a royalty every time their songs were aired on terrestrial radio stations.

The bills face opposition from a number of deep-pocketed rivals, including iHeartMedia and Cumulus, the largest radio broadcasters in the United States, and Google. And some people think that the greatest hope for their passage comes from vocal, passionate advocacy coming directly from the people who stand to benefit the most.

“As someone who works inside the policy world, you know that policymakers can't do it themselves,” Kwende Kefentse, a project officer of cultural policy for city of Ottawa, said. “It's about community organization. That's going to move the needle on any of these issues.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.