NASA: Antarctic Ice Flow Map a 'Game Changer' [VIDEO]

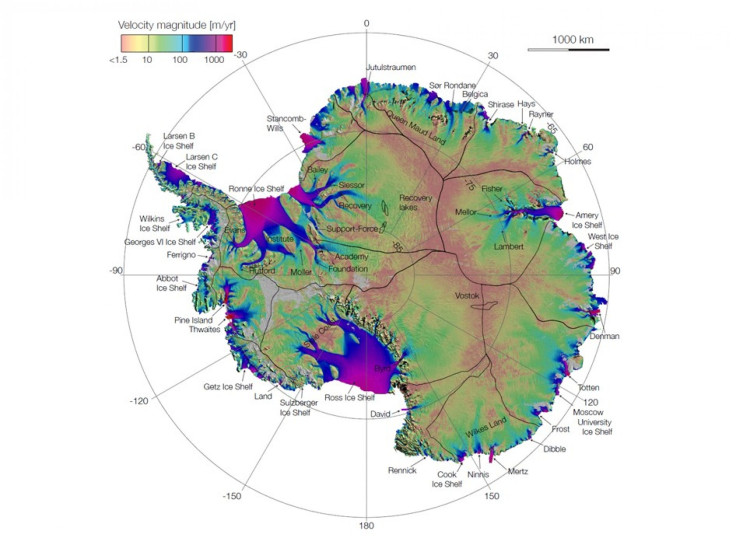

NASA-funded researchers have created the first complete map that details the speed and direction of ice flow in Antarctica, giving critical insight into future sea levels.

Using radar observations from a consortium of international satellites, scientists now have insight into glaciers flowing thousands of miles from the continent's deep interior to its coast.

This is like seeing a map of all the oceans' currents for the first time. It's a game changer for glaciology, said Eric Rignot of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., and the University of California (UC), Irvine.

Researchers used billions of data points captured by European, Japanese and Canadian satellites to weed out cloud cover, solar glare and land features masking the glaciers.

With the aid of NASA technology, the team painstakingly pieced together the shape and velocity of glacial formations, including the previously uncharted East Antarctica, which comprises 77 percent of the continent.

We are seeing amazing flows from the heart of the continent that had never been described before, Rignot said. Indeed, the map is already giving insight into Antarctic dynamics not understood before.

The scientists discovered a new ridge splitting the 5.4 million-square-mile (14 million-square-kilometer) land mass from east to west. They also found unnamed formations moving up to 800 feet (244 meters) annually across immense plains sloping toward the Antarctic Ocean and in a different manner than past models of ice migration.

The map points out something fundamentally new: that ice moves by slipping along the ground it rests on, said Thomas Wagner, NASA's cryospheric program scientist in Washington. That's critical knowledge for predicting future sea-level rise. It means that if we lose ice at the coasts from the warming ocean, we open the tap to massive amounts of ice in the interior.

The paper was published online Thursday in Science Express.

The work was done in conjunction with the International Polar Year, or IPY (2007 to 2008).

The collaborators that worked under the IPY Space Task Group included NASA; the European Space Agency (ESA); Canadian Space Agency (CSA); Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency; the Alaska Satellite Facility in Fairbanks; and MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates of Richmond, British Columbia, Canada.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.