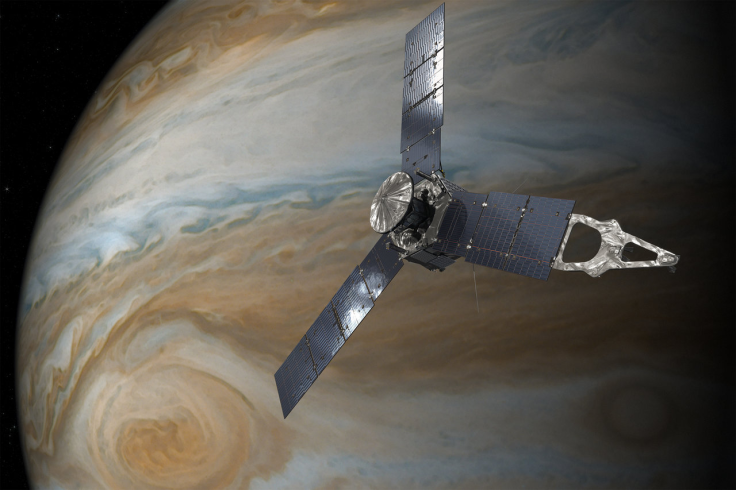

NASA’s Juno Spacecraft Preps For Third Close Flyby Of Jupiter

NASA’s Juno spacecraft, locked in orbit around Jupiter since July 4, will make its next close flyby of the planet at 12:04 p.m. EST on Sunday, the space agency announced Friday. This would mark the solar-powered spacecraft’s third close flyby of the gas giant.

Although the science instruments on board Juno collected data during the first close pass over Jupiter in August, revealing that the planet’s magnetic fields and aurora are bigger and more powerful than originally thought, they failed to do so during the second flyby in October, when the spacecraft unexpectedly went into a safe mode.

I’m back, baby! My 3rd science flyby of #Jupiter is Dec 11. Closest approach = 2,580 miles above the cloud tops https://t.co/RhceuYfPQZ pic.twitter.com/YQTlQifZDz

— NASA's Juno Mission (@NASAJuno) December 9, 2016

“This will be the first time we are planning to operate the full Juno capability to investigate Jupiter's interior structure via its gravity field,” Juno Principal Investigator Scott Bolton from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas, said in a statement. “We are looking forward to what Jupiter’s gravity may reveal about the gas giant's past and its future.”

During its closest approach in the upcoming flyby, the spacecraft would soar just 2,580 miles above Jupiter’s cloud tops. Seven of its eight science instruments would be switched on to gather data when this happens.

A few days before its second close flyby on Oct. 19, NASA was forced to postpone a maneuver that would have shortened the Juno’s orbital period from its current 53.4 days to 14 days. The decision was made after scientists at NASA discovered that a pair of check valves that regulate the flow of helium to Juno’s engines was malfunctioning.

“We have a healthy spacecraft that is performing its mission admirably,” Rick Nybakken, project manager for Juno from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in the statement. “What we do not want to do is add any unnecessary risk, so we are moving forward carefully.”

Juno was launched in August 2011 and traversed nearly 2 billion miles of space to reach Jupiter. The primary goals of the $1.1 billion mission are to find out whether Jupiter has a solid core, and whether there is water in the planet's atmosphere — something that may not only provide vital clues to how the planet formed and evolved, but also to how the solar system we live in came into existence.

In total, Juno is expected to perform three dozen flybys over the next one and a half years. At the end of its mission, Juno will dive into Jupiter’s atmosphere and burn up — a “deorbit” maneuver that is necessary to ensure that it does not crash into and contaminate the Jovian moons Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.