Neil Armstrong Almost Died A Year Before The Moon Landing

Neil Armstrong’s public image is almostly completely composed of one moment from his life: the second his boot touched the surface of the moon in 1969, when he took one small step for a man and one giant leap for mankind. That may be the most important story in his legacy, and the one that many people reflect on during the fifth anniversary of his death on Friday, but there was a lot more to the first man on the moon.

Armstrong was known for his cool head and his humility. Those qualities came out one particular day about a year before his fateful step, when he was a test pilot in a vehicle that crashed and nearly killed him.

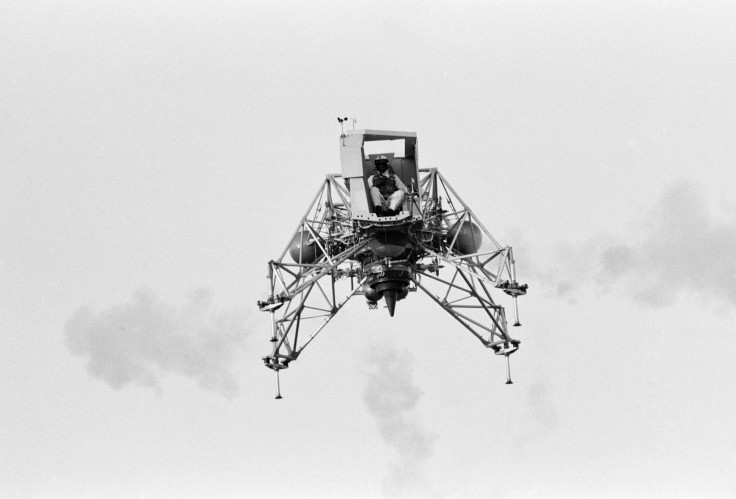

On May 6, 1968, Armstrong was flying in the lunar landing research vehicle less than 100 feet up when he lost control over it and had to eject. NASA was recording the flight and captured the astronaut ejecting from the vehicle moments before it crashed down and exploded. The space agency reported that “the vehicle was a total loss in the ensuing crash.”

If Armstrong had ejected any later, he would have died. Instead, the only injury he sustained was “a hard tongue bite,” Smithsonian magazine said.

The pilot had to make a quick decision when he bailed out. “There was very little time to analyze alternatives at that point,” he said years later, as part of a NASA oral history project. “It was just because I was so close to the ground, below 100 feet in altitude. So again, time when you make a quick decision. You departed.”

The incident occurred at Ellington Air Force Base, near Houston. Smithsonian magazine explained that the pilot was simulating a descent to the moon’s surface when “leaking propellant caused a total failure of his flight controls and forced an ejection.”

Perhaps the most amazing part of the story comes after the ejection, however.

According to an account from the astronaut’s biography, First Man by James Hansen, Armstrong returned to his desk the same day and was casually working. About an hour later another astronaut, Alan Bean, overheard people talking about the crash and went to confirm the story. Armstrong reportedly replied, “I lost control and had to bail out of the darn thing.”

“I can’t think of another person,” Bean later said, according to the biography, “let alone another astronaut, who would have just gone back to his office after ejecting a fraction of a second before getting killed.”

According to NASA historian Bill Barry, Armstrong had previous experience with ejection, during the Korean War.

Armstrong was a Navy pilot and flew dozens of combat missions during that war.

The lunar landing research vehicle, the precursor to the lunar module that he used to land on the moon, was a very different bird from a Navy plane. In his oral history project, Armstrong described it as looking “like a tin Campbell Soup can sitting on top of some legs.”

With a single vertical engine beneath the vehicle, flying it was “somewhat like balancing a pencil on its sharp point on your fingertip,” Barry told International Business Times. Whereas pilots today have “flight control computers that could make minor adjustments thousands of times each second and that would make the job relatively easy,” in Armstrong’s day he had to do all that heavy-lifting.

“It was harder to fly than the lunar module, more complicated, and subject to the problems that wind and gusts and turbulence and so on introduce, that you don’t have on the moon,” Armstrong said. “The systems were somewhat choppier or less smooth than the actual lunar module … The lunar module was a pleasant surprise.”

Armstrong would not have made it to the moon the next year and become an American icon if flying expertise, quick thinking and perhaps a little bit of luck hadn’t come together to save his life that day.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.