Neutrinos May still Have Broken Light Barrier - or Not

(Reuters) - Neutrinos which appeared to have undermined a basic law of the universe by exceeding the speed of light might have done so even faster than first thought - or might not have done it at all, physicists in Italy said on Thursday.

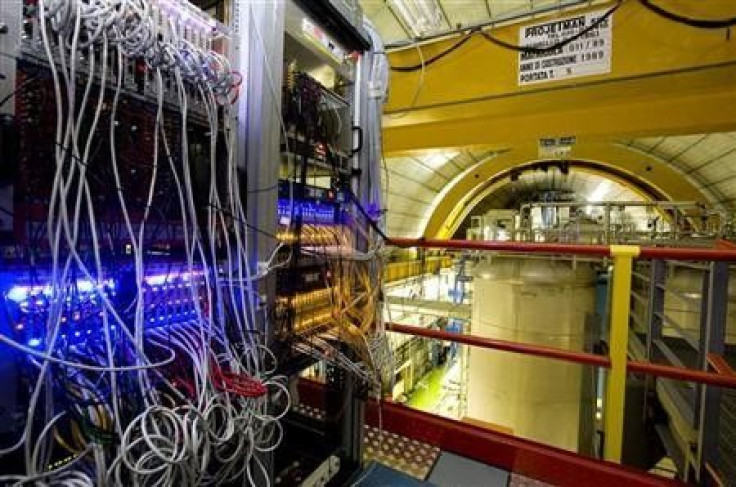

The scientists at the Gran Sasso laboratory said tests on the equipment used in their experiment had led to two question marks over its sensational results, because of problems with possibly faulty cabling and separately with a timing mechanism.

The first "could have led to an underestimate of the time of flight of the neutrinos" while the second could have resulted in "an overestimate," said the statement by the Italian laboratory's OPERA group of neutrino specialists, relayed by the CERN particle physics research centre in Geneva.

The latest turn in the story, which set the scientific world in uproar when it first broke last September, left the basic question - did they or didn't they? - unanswered, with more tests set for the coming weeks and months.

In an interview with Reuters, CERN director general Rolf Heuer said the lack of certainty was normal.

"Last September, the OPERA researchers said clearly the reading of the speed was an experimental result that had to be cross-checked," said Heuer, from whose centre the neutrinos are pumped underground to Italy.

"They have continued to check and check and check, and now they have found these two possible effects, one going in one direction and the other going in another," said the CERN chief. "This is how science should be done."

SKEPTICISM

Most scientists had been skeptical about the original measurements, which flew in the face of Albert Einstein's 1905 Special Theory of Relativity which asserts that nothing in the universe can travel faster than light and underpins much of modern physics and cosmology.

Edward Blucher, chairman of the department of physics at the University of Chicago, said at the time the finding - which inspired floods of jokes in the world scientific community - would have been "breathtaking" if it were true.

One popular joke, playing with ideas of time travel that OPERA's first announcement inspired, runs: "What would you like to drink?" the barman asked him. A neutrino walked into a bar.

The international team in Gran Sasso, dug deep in a mountainside, said they had run many tests over three years before going public with the finding. A second experiment last autumn came up with the same result.

Other teams in the United States and Japan working on neutrinos, invisible sub-atomic particles that pervade the universe but pass unhindered through matter, are preparing similar tests.

Dr Alfons Weber at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Oxford, who is currently involved in both the U.S. and Japanese efforts, said on Thursday measuring the speed of neutrinos was very complicated and the OPERA team had done a careful job.

"At this point it is not clear how their newly-discovered effects will influence the final result, and we should wait for their announcements," he said.

"Just as it would have been unwise to jump to the conclusion that the initial results were the result of an anomaly, it would be unwise to make any assumptions now," said David Wark, a particle physics professor also at the Rutherford.

One of what their statement called "possible effects" - or influences leading to an incorrect reading - concerned an oscillator used to provide the time stamps for GPS (global positioning system) synchronizations, the OPERA scientists said.

This could have caused the neutrinos' speed to be registered as faster - a fraction over the speed of light - than it actually was.

The other "effect" related to an optical fiber connector that brought the external GPS signal to the master clock at Gran Sasso "which may not have been functioning correctly when the measurements were taken," the OPERA team added.

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.