Paul Ciancia Facebook And Twitter Dearth: Why Did The Accused LAX Gunman Leave So Few Digital Footprints?

Seconds after authorities released the name of the alleged gunman who opened fire inside a busy terminal at Los Angeles International Airport on Friday, countless reporters and amateur sleuths no doubt turned to Facebook, Twitter and elsewhere as a means of tracking down the suspect’s social media footprints.

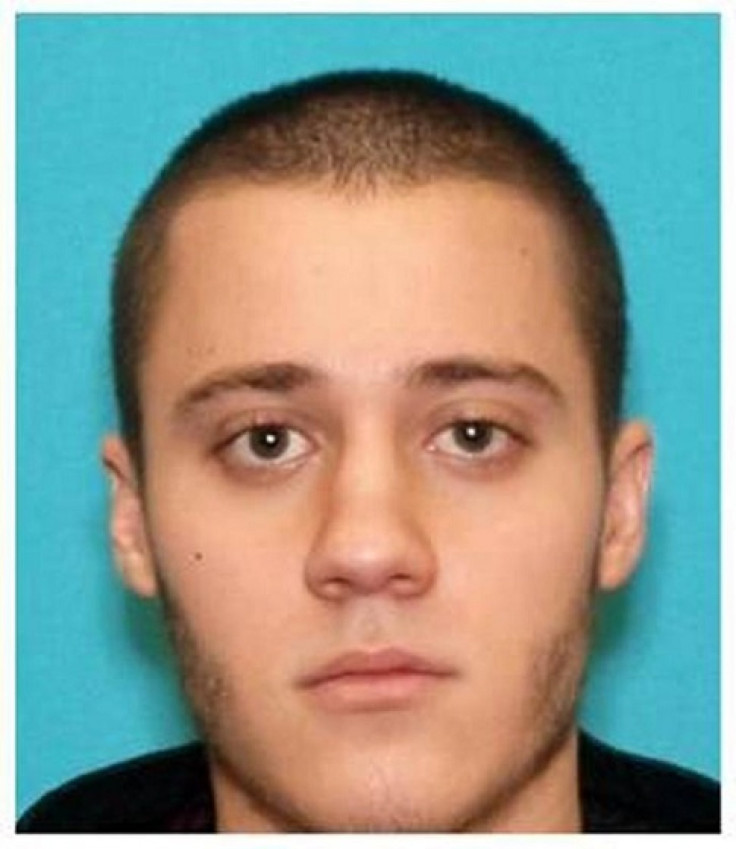

They found very little. Paul Anthony Ciancia, the 23-year-old New Jersey native who police say shot three TSA agents and killed one, had no apparent Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn or any other online profile in his name. If he was active on social media at all, he either deleted his tracks carefully or posted anonymously. It’s one way Ciancia stands apart from many people in his age group (as many as 84 percent of Millennials use social media, according to one recent eMarketer study), but it’s also something he has in common with other young males accused of carrying out recent mass murders.

Adam Lanza, the Connecticut 20-year-old who gunned down 20 children and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School last December, had a virtually nonexistent social media presence. So invisible was Lanza’s online life that Facebook pages sadistically celebrating his actions attracted more attention in the days following the massacre. James Holmes, the former neuroscience student who carried out the “Dark Knight” massacre in Aurora, Colo., was similarly inactive.

Paul Appelbaum, director of Columbia University’s Division of Law, Ethics and Psychiatry, said the absence of social media footprints is not surprising. “Social media are a way of interacting with other people,” he said. “The typical portrait of the young men who commit these awful crimes is that they are outsiders, loners, disconnected from other people.”

Indeed, that narrative is already building around Ciancia, who was described as a “quiet loner” by classmates who spoke with the Los Angeles Times. At the same time, mass shootings are often associated with an element of egotism that, on the surface, may seem wholly compatible with vigorous social media activity. No shortage of studies have examined a link between social networking and narcissism, and some have claimed to find it.

Ciancia, whose shooting spree might have been much worse had LAX police not quickly shot and seriously wounded him, may very well have been seeking some form a validation in the attack -- reportedly, he was carrying a note in which he expressed his displeasure with the U.S. government and said he wanted to kill “TSA pigs.” But that type of validation-seeking is not necessarily inconsistent with online latency.

“Even if you understand their actions as a way to, in part, call attention to themselves, there’s no one cause that leads someone to commit mass murders,” Appelbaum said. “They’re expressions of anger. They’re expressions of revenge. They are, in part, cries for help and assertions of individual importance.”

One outlier in mass-murder suspects is Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the surviving suspect in the Boston Marathon bombing, who left an active Twitter profile behind in the wake of the attack. His older brother Tamerlan, widely believed to be the mastermind behind the bombing, did not appear to have an active social media presence. Shortly after Dzhokhar's Twitter account was discovered, the profile was dissected by law-enforcement authorities seeking to understand his motivation.

In Ciancia’s case, police will not have it so easy. New information is murky and still emerging, and as of right now, the only thing that seems apparent is another broad profile of a violent attack at the hands of a young, angry American male. “We’re still learning about this guy, and we’re going to learn a lot more,” Appelbaum said. “But from what we know right now, he seems to fit the pattern.”

Got a news tip? Email me. Follow me on Twitter @christopherzara

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.