Planetary Scientists Feeling Pinched By NASA Reorganization, Budget Cuts

Anyone who’s worked in a corporate office will know that when the big boss announces “restructuring,” it’s rarely a good sign. Planetary scientists across America are feeling that particular anxiety this week, as NASA tries to reshuffle its organizational deck and deal with looming budget cuts.

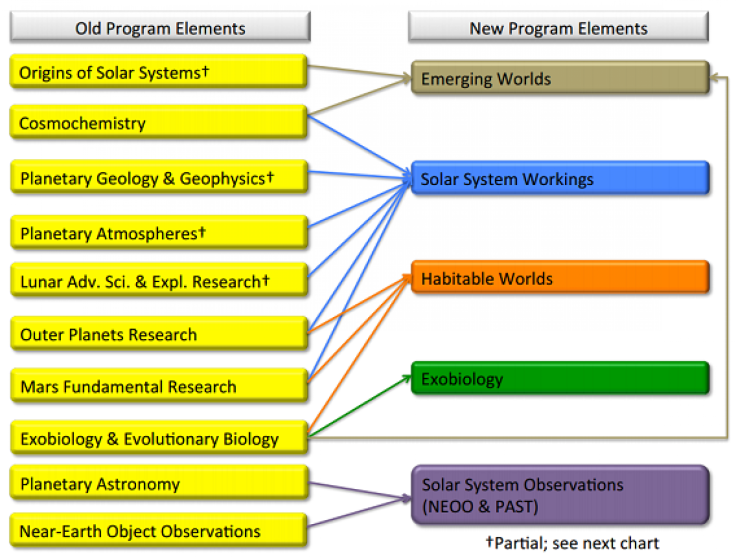

More than 90 percent of planetary science in the U.S. is funded by NASA – this includes people who work directly for the space agency, and scientists who apply for research grants, which can make up a big portion of their salary. Currently, planetary science research grant programs are arranged in dozens of groups. Now NASA wants to consolidate some of these programs.

To a lay person, this might not seem like a big deal. But the bureaucratic devil is in the details.

The biggest point of contention thus far is that Solar System Workings, the new category that will slurp up about half of existing grants, will not be issuing a call for research grant proposals in 2014. This means a funding gap of around a year for a significant portion of planetary science down the line – an especially hard pill to swallow for young scientists that live year-to-year, grant-to-grant. Many researchers who planned on submitting proposals throughout 2014 will now have to wait much longer to see what the future holds.

Mark Sykes, a scientist as well as the CEO of the nonprofit Planetary Science Institute, was blunt in his assessment:

“This is going to destroy American competitiveness in solar system exploration at a time when other nations are rising,” Sykes said in a phone interview.

One of those young researchers in limbo is Scott Guzewich, a postdoctoral researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, who specializes in Martian atmospheric modeling. Guzewich is just 10 months out of graduate school.

“I basically will run out of funding sometime in middle of 2015,” he says. “Between now and then I need to win a grant and have money start flowing to start paying my salary for rest of 2015. But now I can’t submit my proposals to several different research calls.”

Another problem is that consolidating grant programs into a small number of larger pools could make it harder to find impartial researchers to review scientists’ proposals.

“Now everybody’s going to have a conflict of interest,” Guzewich said.

NASA administrators held a "virtual town hall" to explain the reorganization to planetary scientists on Tuesday. It was contentious, to say the least. Scientists took to Twitter to lament the changes under the hashtag #PSDRandA:

Wow. NASA is currently have a Town Hall meeting and essentially telling planetary scientists to look for new jobs. Wow.

- Mike Brown (@plutokiller) December 3, 2013trying to do some science today, but keep getting distracted by how the screwed up #PSDRandA funding means I might not get to this in 2 yrs

- Kat Volk (@kat_volk) December 4, 2013NASA administrators insist that the restructuring is a better way to align the agency’s programs and research interests.

"NASA's commitment to planetary exploration research and analysis activities will remain strong with no lessening of our resolve to continue to lead the world in this area while reflecting fiscal realities,” Jim Green, NASA's Planetary Director, said in a statement on Wednesday.

The planetary science division is already staring down the barrel of some disproportionately high budget cuts. A White House 2014 budget proposal would reduce the planetary division’s funding from a historical average of $1.5 billion to $1.2 billion, while NASA’s overall budget would be reduced by just $50 million. Plus, the sudden rollout of the reorganization – just months before some of the 2014 proposal deadlines – feels a little sudden to some.

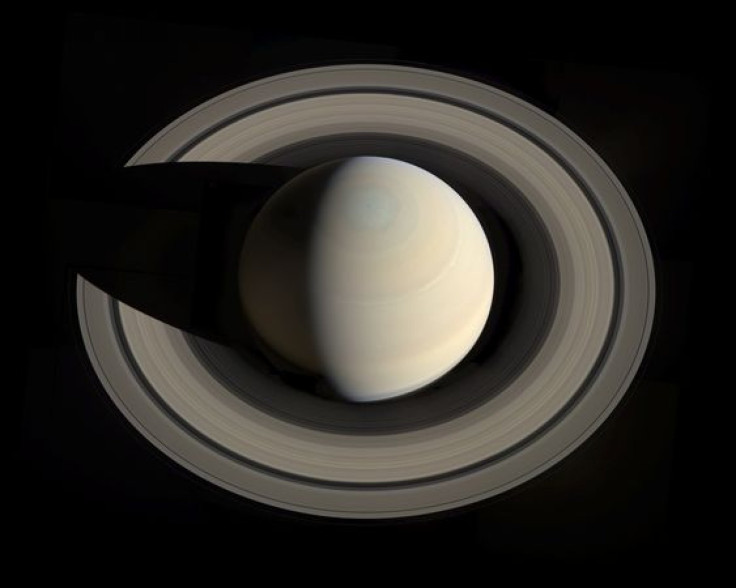

“Usually these things are done relatively slowly, with a lot of consultations with the community,” says Carly Howett, a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute who works on, among other things, analyzing data from the Cassini spacecraft circling Saturn. “People are feeling that [the reorganization] was a done deal by the time it was rolled out.”

Jeremy Boyce, a UCLA geochemist, says he’s completely “pro-NASA” and that the agency does amazing things with a minuscule portion of the federal government’s budget. But he notes that jumping from one research post to another isn’t quite as feasible as changing jobs is in other fields.

“Many people expressed concern for themselves and others at yesterday’s town hall … because the reorganization apparently leaves many scientists without even an opportunity to apply for funding that they need to keep themselves clothed and fed,” Boyce says. “The widespread impression was that this was considered an acceptable loss by NASA administrators, and that people who want to survive need to get on a winning team or leave the field.”

But although many scientists are frustrated with how the reorganization has been introduced, some think it could be beneficial down the road.

“I’m strangely optimistic,” says Britney Schmidt, an assistant professor at Georgia Tech who studies the moons of the outer solar system planets and icy asteroids. “I’m hopeful that the reorganization will actually end up in fewer proposals to write, simpler funding, and faster grant turnarounds.”

Alyssa Rhoden, another postdoctoral researcher at Goddard (her research focus is Europa, Jupiter’s icy moon), says the restructuring highlights existing funding problems.

“It was not an accident that this February [2015] deadline forces us to skip a year,” Rhoden says. “There’s no point in having 500 proposals written, submitted and reviewed if there’s not going to be any funding to pay for the work.”

But who will be lost to the field in the meantime?

“Disproportionately, women and people with families will be forced out,” says Rhoden, who has an 18-month-old son. “You cannot justify staying in a field with zero job security.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.