Political Brinkmanship: Imminent US Debt Ceiling Debate, FY14 Budget Showdown

It’s all quiet on the D.C. front. But the current calm will soon fade. When Congress returns from recess early next month, it will face several hurdles, including the expiration of the resolution to fund the government through the end of September and the need to raise the debt ceiling.

“Beltway brinkmanship is not dead; it’s just sleeping,” said Josh Dennerlein, an economist with Bank of America Corp. in New York. “We expect another flair-up in fiscal uncertainty this fall.”

The return of fiscal uncertainty may even give the Federal Reserve policymakers an additional reason to hold off on tapering at their Sept. 18 meeting. The upcoming fiscal deadlines means that the Federal Open Market Committee will be meeting during the height of the upcoming budget battles. The FOMC may want to leave their insurance policy in place until the battle is resolved.

When Congress returns from its “August” recess on Sept. 9, refreshed, there will be little time left to address a handful of pressing fiscal issues.

As the congressional calendar currently stands, there are only nine “in-session” days left before Oct. 1 – the day when the 2014 fiscal year begins.

The possible outcomes, according to Barclays’ senior U.S. economist Michael Gapen, include a new budget, a continuing resolution to fund the government temporarily while a new budget is drafted, and a government shutdown. Given the significant differences between the political parties on budget issues, Gapen thinks a new FY14 budget in place by Oct. 1 is very unlikely. It’s most likely that there will be a continuing resolution that maintains spending at sequester levels while a new budget is drafted.

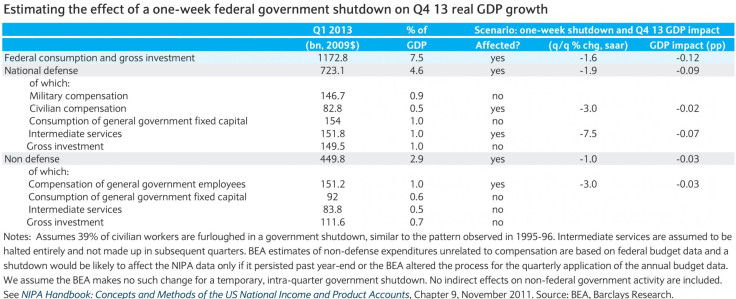

If a government shutdown were to happen, functions of the federal government considered “non-essential” will cease while “essential” functions continue. Gapen examined the economic impact of a one-week government shutdown in the table below. A multi-week stoppage can be estimated by cumulating the one-week effect.

According to Gapen, a temporary government shutdown at the beginning of the fourth quarter could result in shifts in investment spending from one month to the next and increase the volatility of inventory data, but it would not likely disrupt federal consumption of fixed capital and gross investment over the quarter if the situation were resolved before year-end. However, services consumption is unlikely to be recovered once halted.

Barclays’ analysis suggests that a one-week shutdown in October would reduce real gross domestic product growth by 0.1 percentage points in the fourth quarter. This is consistent with the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate that the approximately four-week shutdown in 1995-96 reduced growth by 0.5 percentage points in the last three months of 1995.

Thus, a short federal government shutdown is unlikely to dampen real GDP growth significantly. “A longer shutdown, however, could have negative indirect effects on private sector activity,” Gapen said.

Casting a large shadow over the entire situation is that the Treasury Department is about to run out of cash under the current debt-ceiling limit of $16.7 trillion. The Treasury has said that the use of extraordinary measures will delay the need to raise the debt ceiling until Oct. 11, but Barclays thinks the ceiling is likely to be reached between mid-October and mid-November.

Failure to raise the debt ceiling would require an immediate cut in spending equal to 4.2 percent of GDP.

“We do not believe the worst-case outcomes will come to fruition,” Dennerlein said. “Using recent history as a guide, Congress will come to a last-minute deal that will avert the worse.”

After all, the majority of fiscal policymakers have realized the dangers that threatening to default or shutdown the federal government poses to the economy and thereby to their election prospects.

Gallup’s August poll shows that approval ratings for Congress remain near historical lows, with just 14 percent of Americans saying they approve of the job Congress has done. The yearly average for Congress has reached its lowest level since Gallup began tracking in 1974.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.