Trump Administration Ethics Entanglements: 9 Officials Getting Lobbied By Previous Employers

To fill the position of Secretary of the Army, President Donald Trump first turned to the familiar world of billionaire business leaders and nominated Vincent Viola for the job. But Viola, who made his fortune on Wall Street and owns the National Hockey League’s Florida Panthers, abruptly withdrew his nomination in February, citing difficulties extracting himself from his businesses.

Next, Trump turned to another reliable source of allies — the grassroots of the Republican party — and nominated Tennessee State Senator Mark Green for the position. But Green, a former Army flight surgeon, withdrew his name from consideration in May, citing “false and misleading attacks” based on controversial statements he made regarding gay and transgender rights.

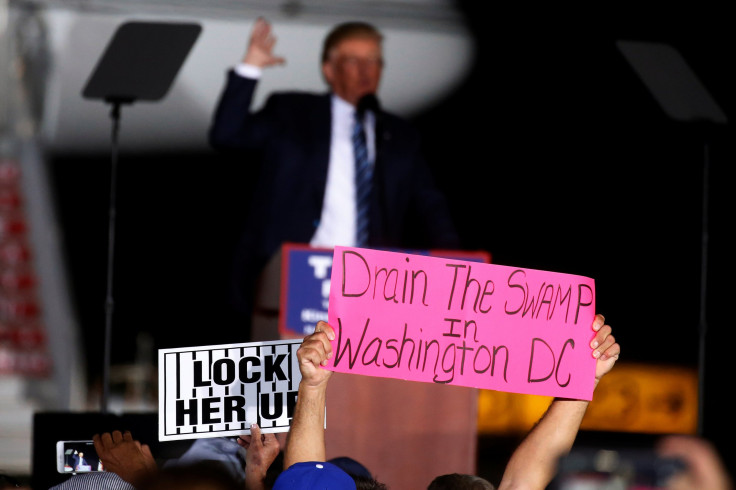

So for his third try at finding his Army secretary, Trump took a different tack. He headed to the swamp, the one he promised to drain, and found a lobbyist.

Trump nominated Gulf War veteran and West Point graduate Mark Esper for the Army Secretary post in July, but his confirmation hearings have not yet been scheduled. However, what’s sure to come up in those hearings is the seven years Esper led the government relations department at Raytheon, where Esper was the top lobbyist at one of the largest defense contractors in the world. This year, Raytheon has already spent millions of dollars lobbying the Department of the Defense, where Esper will work if confirmed by the Senate.

One of Trump’s first actions as president was to institute ethics rules for his administration that were largely based on rules implemented at the beginning of the Obama administration. But in spite of Trump’s promises to “drain the swamp,” a few critical differences between the two ethics regimes mean that Esper can be Trump’s Army Secretary, but couldn’t have been Obama’s.

Lobbyists taking positions in government, and government employees taking positions at lobbying firms, is nothing new in Washington: It’s so common that movement between the two camps is referred to as the “revolving door.” But under Obama’s ethics rules, lobbyists weren’t able to join an executive agency they lobbied for two years. The Trump administration has no such rule, and the administration is taking advantage of that omission: one watchdog group determined a quarter of ex-lobbyists in the administration lobbied on issues they worked on in the prior two years.

The de facto rescinding of the two-year rule is why Esper can jump straight from Raytheon (he was listed as a lobbyist on the company’s most recent lobbying disclosure ) to an agency that Raytheon is lobbying for federal funds and contracts.

If confirmed, Esper will become yet another Trump administration official who is presiding over agencies, departments and offices being lobbied by their former employers, or in the case of ex-lobbyists, former clients.

Many of these officials have signed ethics agreements that forbid them from working on issues that could affect their ex-employers for either a year, or two. Others have been granted waivers for those ethics agreements, waivers which were originally kept secret for months until the White House relented to the increasingly public protests of the Office of Government Ethics and released them at the end of May.

There are federal statutes on the books that prevent executive-branch staffers from working on any matter that they might have a direct financial interest in. But while officials are expected to recuse themselves from matters directly related to their previous employers, no standardardized recusal process exists across the executive branch, and an individual instance of recusal at the White House doesn’t create a public paper trail.

The White House has evaded specific questions from International Business Times, as well as other outlets, about who has recused on what issues, instead replying to questions with general statements about the administration's commitment to ethics.

“The White House takes seriously the need for appointees to resign, recuse and divest where required,” Natalie Strom, a White House spokesperson, told IBT in an email. “The White House Counsel's Office worked closely with all White House officials to avoid conflicts arising from their former places of employment or investment holdings. To the furthest extent possible, counsel worked with each staffer to recuse from conflicting conduct rather than being granted waivers, which has led to the limited number of waivers being issued.”

But while the White House Counsel’s office is in charge of the ensuring proper recusals from actual or perceived conflicts of interest, the office itself is not immune from ethical entanglements. Stefan Passantino, the Deputy Counsel to the President and the White House’s “designated agency ethics official” has provided paid legal services to two Trump administration cabinet members in the last two years: Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson and Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price, according to Passantino’s public financial disclosure.

Passantino also provided services for Icahn Capital, which is led by legendary investor and Trump confidant Carl Icahn. (Passantino recused himself from any matters dealing with Icahn on Jan. 20, according to the New Yorker’s Ryan Lizza.) Until last week, Icahn served as a “special adviser” to the president, a legally ambiguous role that meant the administration's ethics rules didn’t apply to him. It also meant that since he was never serving in an “official role” at the White House, there was no exact date of his departure. But Icahn seemed to have resigned from the role in advance of a New Yorker investigation that found Icahn may have tried to use the position to enrich himself.

Former Office of Government Ethics Director Walter Schaub, who now works for the campaign legal center, tweeted that the New Yorker story was “a perfect window into how the White House Counsel is enabling the Administration to dodge ethics.”

Blackstone CEO Stephen Schwarzman served in a similar non-official adviser role not covered by ethics rules as chairman of the White House’s Strategic and Policy Forum until last week, when the advisory panels were disbanded amid criticism of Trump’s response to a white supremacist rally in Charlottesville.

In addition to the murky ethical questions surrounding Trump’s unofficial advisers, the White House has decided to not publicly release the White House visitor logs, which makes it difficult to tell which lobbyists and business executives may be meeting with White House staff. (On Tuesday, the Secret Service agreed to stop erasing White House visitor log data until a lawsuit brought by Public Citizen seeking access to those records can be decided.)

While there are many obstacles that prevent the public from knowing exactly what issues are being worked on, by whom, in the executive branch, and whether ethics rules are being fully enforced, what is publicly available are lobbying records. By examining those records, IBT has compiled a list of executive branch officials who are running, or part of, agencies that are being lobbied by their former employers or clients. There is no indication that the people are on this list have broken any laws, or their ethics agreements, which have required them to recuse themselves.

Instead, the list, which is not comprehensive, shows where a specific kind of ethical entanglement can occur in this administration. It is is simply a survey of Trump’s swamp and a compilation of some of that swamp’s murkiest waters.

White House Deputy Director of Legislative Affairs Amy Swonger

After serving as a congressional aide to Republican Senators Mitch McConnell and Trent Lott last decade, and working a stint in Vice President Dick Cheney’s office, Amy Swonger traveled through Washington’s busy revolving door to become a lobbyist in 2008. After working at two lobbying firms, Ernst & Young and Invariant LLC (the latter of which was run by Hillary Clinton fundraiser Heather Podesta), Swonger joined the White House in March to lead the Trump administration’s Senate legislative affairs team. In 2015 and 2016, Swonger had nearly 40 lobbying clients across a diverse set of industries. Records show that in 2017 roughly half of those clients, 18 in total, have lobbied the White House Office or the Executive Office of the President, which contains the White House Office.

According to White House ethics rules, Swonger cannot work on issues related to her former clients for two years. This presents Swonger with a complicated web of conflicts and recusals to navigate, which she has done without the help of an ethics waiver, according to public ethics waiver disclosures. Swonger’s recent clients that have lobbied the White House include NextEra Energy, Dow Chemical, Pfizer, Dish Network, National Association of Real Estate Trusts, Marathon Oil, Marriott International, Johnson & Johnson and the Securities Industry and the Financial Markets Association.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson

Rex Tillerson spent 31 years at oil giant ExxonMobil before becoming Chairman and CEO of the company in 2006. The former engineer resigned his position on December 31, 2016 to lead the Trump administration’s State Department. As he’s been running the U.S.’s diplomatic corps, and demonstrating himself to be one of the most media-averse secretaries of state in recent memory, Exxon has been lobbying the State Department.

Exxon lobbying filings from this year that list the State Department as a lobbied organization have a price tag of $3.4 million. Records show that Exxon lobbied on issues that would fall under the purview of the State Department, including “Discussions related to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)” and “Discussions related to energy infrastructure and investment.”

So far in 2017, Exxon has listed eight registered in-house lobbyists in its filings, and it employs another eleven lobbying firms to fight for its interests in Washington. But that's hardly the extent of the company's influence. The dues it pays to industry trade associations also help pay for the lobbyists those associations hire. Exxon is a member of the American Petroleum Institute, which also has a multi-million dollar a year lobbying apparatus. The API didn’t lobby the State Department in 2016, but it has listed the department as one of its lobbied agencies in both of its filings in 2017, the year Tillerson took the helm.

Some of the areas it lobbied include “efforts related to the renegotiation of NAFTA,” and “efforts related to the export of natural gas, petroleum and petroleum products.” Exxon is also a member of the Brazil-U.S. Business Council, which lobbied the State Department on the “promotion of U.S.-Brazil trade and investment relations.”

Tillerson signed an ethics pledge filed with the Office of Government Ethics that said “for a period of one year after my resignation from ExxonMobil, I will not participate personally and substantially in any particular matter involving specific parties in which I know ExxonMobil is a party or represents a party, unless I am first authorized to participate."

Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao

Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao, who was labor secretary in the George W. Bush administration, served on the board of Alabama-based Vulcan Materials from February 2015 until she resigned the position to serve in the Trump administration.

Vulcan calls itself the “nation’s largest producer of construction aggregates,” which means it is a huge supplier of gravel, sand, and crushed stone — products that are needed in vast quantities to build highways and other infrastructure projects. Since the government has a central role in these kind of projects, Vulcan often lobbies the Department of Transportation. In the first two quarters of 2017, Vulcan has hired four lobbying firms and one of them, Ice Miller Strategies, has lobbied the Transportation Department on just one issue: the reauthorization of the Federal Highway Administration, which manages federal funding of maintenance and construction of highways.

Chao’s ethics agreement states only that she will “not participate personally and substantially” in any matter that has a “direct and predictable effect” on Vulcan until her deferred stock is redeemed. There is no mention of a year-long, or two year-long, recusal from matters related to Vulcan in Chao’s ethics agreement. Chao is also the wife of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

Secretary of Defense James Mattis

Defense Secretary James Mattis was the first member of Trump’s cabinet confirmed by the Senate, which voted 98-1 to confirm the retired Marine general and former U.S. Central Command leader. Mattis left the Marines in 2013, and soon joined the boards of several organizations and companies, including scandal-plagued biotech startup Theranos and General Dynamics, one of the nation’s largest defense contractors and the receipient of $14.5 billion worth of federal contracts in 2016, according to the General Services Administration.

General Dynamics, like most large military contractors, spends millions of dollars a year on lobbying the Defense Department to secure contracts and steer business its way. Of the $7.2 million dollars on lobbying General Dynamics has spent this year, filings representing $6.2 million of that total list the Defense Department as one of the lobbied entities. The company lobbies on a variety of topics, but a survey of company lobbying filings show the company is mainly lobbying on appropriations. One filing identifies lobbying issues as “Department of Defense issues and funding (research & development and procurement) related to: shipbuilding; submarines; ground vehicles; aircraft; communications systems; defense intelligence programs; ammunition and weapon systems; military information support operations.”

In his ethics agreement letter, Mattis said he would not participate in any matter involving General Dynamics for a year. He also said he would divest all of his General Dynamics stock and vested stock options.

Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross

Billionaire investor and Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross’s efforts to disentangle himself from his financial conflicts was trickier than most Trump administration appointees due to the sheer size of Ross’s personal holdings. His financial disclosure form filed in December listed current positions with more than 50 organizations and companies. One of those companies, a Luxembourg-based steel and mining firm called ArcelorMittal, has been lobbying the Commerce Department this year. Ross became a director at ArcelorMittal in 2008, and in 2017 the company’s U.S. division has spent more than a million dollars on lobbying.

The ArcelorMittal lobbying filings that list the Commerce Department as a lobbied entity indicate the company was lobbying on international trade matters, including “Chinese government policies promoting steel overcapacity and unfair trading practices,” “strong enforcement of U.S. trade laws,” and issues related to “currency manipulation,” “global steel overcapacity” and NAFTA. Ross signed an ethics agreement that said he would not involve himself in matters involving ArcelorMittal, and a number of other companies he held positions in, for a year after his resignation from those companies.

National Economic Council Director Gary Cohn

Gary Cohn jumped straight from his job as the president of Goldman Sachs to become Trump’s top economic advisor and director of the White House’s National Economic Council (NEC). In doing so, he got a $285 million payout from the investment bank that included favorable terms on stock options that raised concerns among ethics experts.

Last week, IBT reported that Cohn’s NEC had been lobbied by at least three trade associations and industry groups that count Goldman Sachs as a member. They included the Investment Company Institute, the Managed Funds Association, and the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. Together, the three groups spent $3.6 million on government lobbying in the first two quarters of 2017.

Deputy Interior Secretary David Bernhardt

Sworn in this morning by @SecretaryZinke, and now time to get to work! #ServingThePeople pic.twitter.com/uB0bk8xusb

David Bernhardt was a lobbyist for lobbying firm Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck in the late nineties before joining the Department of the Interior during the Bush administration. He then returned to Brownstein as a partner and eventually launched the firm’s Energy, Environment and Resource Strategies Division. Earlier this year, Bernhardt took one more trip through the revolving door, returning to government to become the number two official at Trump’s Interior Department, which oversees the National Parks Service, as well as all federally-owned land. His ties to oil and gas industry clients led a Democratic Congressman to call him a “walking conflict of interest.”

Two of Bernhardt’s immediate former clients have lobbied the Interior Department through Brownstein in 2017, including California’s Westlands Water District, which sued the Interior Department four times while a Bernhardt client, and the Navajo Nation.

While not clients of Bernhardt specifically, other clients of Bernhardt’s firm, where he was a partner, have also lobbied the Interior Department this year. These include mining and oil and gas interests like Gemfield Resources, Statoil, WPX Energy, and Taylor Energy Company, among others.

One client that did hire Brownstein to lobby the Interior Department this year is the Governor’s Office of the State of Colorado, which has never hired a federal lobbying firm before this year, according to federal filings. Those filings indicate that Gov. John Hickenlooper, a Democrat, spent a total of $70,000 of taxpayer money to hire Brownstein to lobby the Justice Department, the Interior Department, the EPA and Congress on “issues related to federal funding for national service programs” and fiscal year 2017 and 2018 appropriations. Hickenlooper also hired Brownstein to lobby Congress on “issues related to healthcare.”

Hickenlooper’s office said the decision to hire Brownstein had nothing to do with Bernhardt, who is a Colorado native.

“Our office hired a lobbying firm after the new administration came in, anticipating that we would need to build key relationships with the new administration. We recognized we would be navigating possible changes in the federal approach to issues of importance to states including energy policy, health care, marijuana and the environment to name a few. We wanted to ensure Colorado had a voice as these issues were discussed,” Hickenlooper’s press secretary Jacque Montgomery told IBT in an email.

“Our decision had nothing to do with Mr. Bernhardt, who left for the Department of Interior after we hired BHFS. We think it's important to work with a firm that has ties to Colorado. BHFS is the only lobbyist with headquarters in Denver,” Montgomery said.

In his ethics agreement, Bernhardt said he would refrain from involving himself in matters dealing with his former firm, and former clients, for one year.

Special Assistant to the President for Domestic Energy and Environmental Policy Mike Catanzaro

Trump Names Industry Lobbyist and Climate Science Denier Mike Catanzaro as Top White House Energy Aide https://t.co/7SuRY04dwA pic.twitter.com/ZhEULFNDbx

As a registered lobbyist for lobbying firm CGCN in 2015 and 2016, the former Congressional and White House staffer and EPA Associate Deputy Administrator Michael Catanzaro represented a variety of oil and gas, mining and energy clients. Earlier this year, he joined the NEC as the Special Assistant to the President for Domestic Energy and Environmental Policy. As several of his former CGCN clients have lobbied the NEC in 2017, including Boeing, Koch Companies, Microsoft, General Motors, Financial Services Roundtable, Investment Company Institute and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the White House granted Catanzaro an ethics waiver that allowed him to break his ethics agreement in order to “participate in broad policy matters and particular matters of general applicability relating to the Clean Power Plan, the WOTUS rule,” also known as the EPA’s clean water rule, and “methane regulation.”

Department of Homeland Security Deputy Chief of Staff Chad Wolf

Former Wexler Walker lobbyist and Bush-administration TSA official Chad Wolf lobbied Congress on behalf of Analogic Corporation in 2015 and 2016 and pushed the company’s airport security technology. In December of 2016, Analogic announced that its new ConnectCT screening system would undergo TSA testing (that testing is still ongoing ). A few months later, Wolf became the chief of staff at the TSA. Then, In July, Wolf was promoted to Acting Deputy Chief of Staff at the Department of Homeland Security, the TSA’s parent agency.

Two of Wolf’s former clients have lobbied the Homeland Security Department in 2017. One is robotics and automation technology company ABB, which lobbied the agency on “Energy Efficiency,” and “Grid Security & Resilience,” according to federal records. The other is the National Association of Software and Services Companies (NASSCOM), which lobbied DHS on “high skill immigration,” “green cards,” and “visa processing.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.