Private Equity And Social Responsibility: The Odd Courtship Between Private Finance And Public Causes

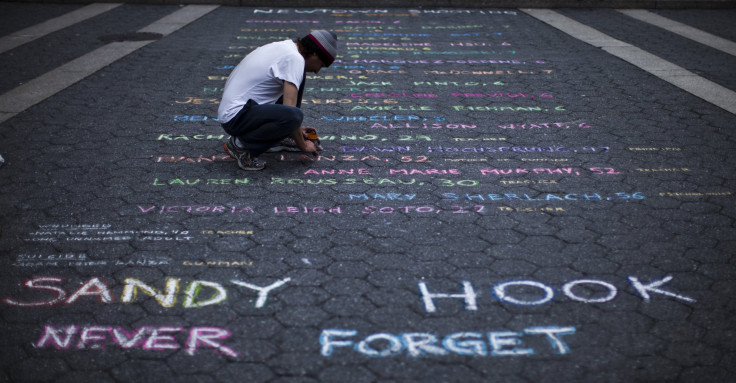

Almost a year after the Newtown, Conn., shootings, one key player could be drawn out of the massacre’s long shadows once again.

Campaign to Unload, a coalition critical of investments in gun manufacturers, plans fresh actions – potentially, protests and online petitions – in the coming weeks, targeting private equity giant Cerberus Capital Management LP.

The campaign protested outside Cerberus’ New York headquarters in September, demanding that Cerberus fulfill its December 2012 promise to exit its investment in the Freedom Group Inc. weapons manufacturer. The Freedom Group makes the Bushmaster rifle used in the Newtown school shootings, which left 26 dead, 20 of them children.

Campaign executive director Jennifer Fiore told International Business Times that the coalition will ramp up activities to mark the upcoming anniversary on Dec. 14, though she declined to give details.

“A number of investors, including [state pension fund] CalSTRS, have been investigating its investments with Cerberus since this Newtown episode,” Fiore said. “We'd love to see Cerberus take the high road and be a leader, and sell its investments in gun manufacturers.”

“We consider it blood money,” she said.

Cerberus declined to comment for this article. In December last year, the private equity and finance firm, which manages more than $20 billion, pledged to sell off its 2006 investments in the nearly $1 billion Freedom Group, one of the largest arms wholesalers in the U.S.

At the time, Cerberus said in a statement: “As a Firm, we are investors, not statesmen or policymakers. Our role is to make investments on behalf of our clients… It is not our role to take positions.”

The statement did not explain why the company was selling its stake; activists say the sale was likely done to avoid bad publicity. Cerberus owns a majority stake in Freedom Group, and its move is effectively a sale of Freedom Group, though interested buyers seem scarce.

A Sept. 29, 2013, regulatory filing from Freedom Group – aka the Remington Outdoor Company, the namesake of the popular weapon – notes that “a competitive sales process” of Cerberus’ stake is ongoing.

The Cerberus debate – a small detail in the broader private equity landscape – represents an intriguing trend toward incorporating environmental, social and corporate governance (or ESG) factors in the traditionally apolitical business.

So-called socially responsible investing has been creeping quietly into the high-finance lexicon, and the private equity industry – initially slow to give it credence – appears to be coming around. Unsurprisingly, considering the industry’s emphasis on the bottom line, some wonder if the new interest in ESG is mere lip service. But for whatever reason, environmental and social considerations are increasingly coming into play.

Private equity firms typically buy distressed public companies, rework them behind closed doors, and then sell them (often years later) for profit. The public typically doesn't notice what these companies do from day to day, but they came under scrutiny in the 2012 U.S. presidential election, with Republican candidate Mitt Romney taking fire for his work with private equity giant Bain Capital. Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner is also heading to private equity, joining New York’s Warburg Pincus LLC as a managing director.

This slice of private finance, which raises money from pension funds, university endowments and wealthy individuals, is led by hard-nosed dealmakers and was worth $186 billion in buyout deals in 2012, according to Dealogic.

Still, the real motivations behind an apparent private equity pivot to social and environmental issues are complex and sometimes intentionally obscure. Caring about the dirty deeds and corporate responsibility of companies they own could be basic damage control by private equity firms, who want to avoid “reputational risk,” as it’s known in industry jargon.

Newtown and a recent European horse meat scandal were cited at a New York industry panel in September as recent cases where smart responses by private equity firms were needed.

In the February 2013 horse meat case, global frozen-food distributor Findus sold horse meat to unwitting U.K. shoppers. Findus’ part owner, U.K. private equity firm Lion Capital, felt the sting of headlines and publicly criticized Findus’ handling of the scandal.

A Lion Capital founder said at the time that the scandal could make them rethink their private equity investment strategies. Others blamed Lion directly for cost-cutting measures it imposed on Findus, alleging the measures led to the cheaper horse meat substitute.

“Lion will have to fight hard to dissociate its image from dodgy processed-food companies,” wrote a Reuters columnist earlier this year.

Other scandals that have touched private equity include the April 2013 Bangladesh factory collapse.

Private equity giant KKR & Co. LP (NYSE:KKR) emailed selected portfolio companies after the Bangladesh collapse killed hundreds, asking if they had any involvement in the region, according to KKR’s environmental and social specialist Elizabeth Seeger. Seeger told IBTimes none of KKR’s portfolio companies were directly involved in the Bangladesh collapse. She declined to name the companies she emailed but said that KKR held a webinar shortly after the incident, reviewing company best practices and trends for Bangladesh.

“We didn’t need to warn them of the sensitive environment,” Seeger said.

According to an earlier company report, KKR reviewed three companies in 2013 for responsible sourcing practices, and has trained more than half of its 80 or so portfolio companies on responsible sourcing since 2010.

Concerns about brand risk also come from another quarter: Private equity’s funders are firing up pressure from below, demanding that risks be minimized.

Private equity strategist Andrew Malk, who specializes in ESG and private equity, said pressure from large investors is the single strongest driver of private equity’s turn to socially smart investing.

The increasingly loud message from big investors: “We want good risk-adjusted returns from our private equity allocation, but we want that return with as little environmentally and socially negative impact as possible,” Malk told IBTimes.

Some institutional investors have rigid exclusion policies, and as a result, won’t invest in the arms sector, tobacco companies or gambling.

The world’s largest pension fund for educators, California’s $171 billion CalSTRS, decided to quit certain arms investments in January 2013. In 2008, they stopped investing in tobacco companies, a fund representative told IBTimes in an email. They’ve also divested from some companies that do business with Iran and Sudan.

CalSTRS has invested $751 million across Cerberus’ diversified financial units – a well-known tie between the private equity and big investor world. CalSTRS’ former $11.7 million stake in firearm holdings included an $8.8 million stake in the Freedom Group, which they are still waiting on Cerberus to sell.

Notably, the financial crisis also changed institutional investors’ attitudes toward how private equity handles their money. Pre-crisis, investors lined up at the doors of private equity funds, eager to participate in profitable deals, said James Gifford, the former head of the United Nations’ Principles for Responsible Investment.

“Post-crisis, capital dried up and things completely reversed,” he told IBTimes. “Private equity funds realized they really needed to respond to what clients were demanding.”

Those with the money pushed dealmakers to consider traditionally "soft" factors such as environmental impacts or employee treatment in investment decisions, Gifford said. Post-crisis, private equity firms had to improve the actual operations of their portfolio companies, he added. Previously, they relied on financial restructuring and leverage to deliver value in rising equity markets.

“We’re talking about energy efficiency, or investing in human capital and good corporate governance, to prepare a firm for an exit,” Gifford said. “These sorts of factors are core to delivering strong companies into public markets.”

The U.N. group has signed up hundreds of major investment managers and asset owners to its framework, which holds them to certain human rights and environmental standards. These investors in turn often push private equity firms. Several of the latter have signed themselves up directly, too.

One key unresolved question may drive investor pressure. It also opens up a new frontier in the debate: Can attention to social and environmental issues deliver solid financial returns?

The answer: No one knows. But everyone has opinions.

Social investment specialist Rina Kupferschmid-Rojas notes that when a private equity-backed firm launches publicly or is sold, there theoretically won’t be a lesser company value from a damaged brand. She even founded a firm, ESG Analytics, which gauges how well private equity firms do on environmental and social impacts. The industry lacks solely needed metrics, which is partly why there is a lack of clarity on this topic, she said.

As for financial returns: “We are not at the point to say: ‘Yes, you’re going to generate more alpha [returns],’” from these considerations, Kupferschmid-Rojas said. “But at least you’re not going to get a discount.”

The question has long befuddled analysts and industry insiders. There is no conclusive research showing that social responsibility delivers better financial returns, in new revenues or broader profit margins. Firms can cut costs by being more environmentally friendly and energy efficient, for instance, but it isn’t clear that they generate substantial new revenues by tapping into the social consciences of consumers in some way.

On the contrary, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP found in an October report that only 15 percent of dozens of firms surveyed believed that positive financial value could be created by focusing on these issues. In research done earlier this year, UBS AG (VTX:UBSN) analysts also found that investors who care mostly about financial returns have no special reason to prefer companies with an environmental or social mission. Even with an “explosion of research” into corporate social responsibility since 2006, hard conclusions on the topic are still murky, analysts said then.

Some pension funds, like CalSTRS, have a plain policy on the issue. “Geopolitical and social risk factors can only be taken into consideration to the extent that such factors bear on the financial advisability of the investment,” reads the CalSTRS investment policy. In other words, investments can’t be selected or rejected solely on social considerations, but must measure up from a business perspective, too.

Given such skepticism, it’s unsurprising that the speed of the take-up of ESG issues by private equity players varies.

A November 2012 report by private equity researcher PitchBook found that more than half of 48 private equity firms polled had no environmental or social initiatives at their firms, and of the firms surveyed, 45 percent didn’t plan to start paying attention to these topics in the future.

If that sounds like a solid counter-trend, it’s worth remembering that these considerations just aren’t that relevant to many sectors. Clothing retailers and iPad manufacturers may be concerned about supply chains, and oil drillers may recognize the cost of doing business in environmentally insensitive ways, costs that often take the form of lawsuits. In contrast, cloud computing firms and data researchers leave light footprints.

Smaller private equity firms, especially those with assets under $1 billion, also tend to trail larger rivals on socially responsible investment.

Likewise, small pension funds may lack the know-how and drive to consider complex social criteria in their portfolio picks.

Still, as the worlds of private equity and smart social investment slowly and steadily converge, interesting personnel shifts happen, too.

Gifford, who led the United Nations’ responsible investment monitor for seven years and signed up hundreds of entities, each worth millions or billions, to its responsible investing framework, is now moving from platforms and principles into private equity, he told IBTimes. His successor at the U.N. has not been selected yet.

“I really have been speaking about responsible investment for many years, and I feel it’s now my time to do it,” Gifford said. “I feel private equity is the area where it is most real, the most close to the ground.”

Though he doesn’t yet know which private equity firm he will join, Gifford stressed that the move doesn’t signal that reform from within finance is faster or more effective than public sector work.

“For me, it’s a personal decision, and not a decision about where I feel the most amount of difference can be made,” he said. “They are two different ways [to effect change]. One is not faster than the other.”

Pressure from activists for quick and profound reactions to tragedies may be unrealistic, as the private equity industry hesitates on this topic. But most industry insiders note that ESG – a factor rarely mentioned in investment conferences in the past – is surfacing more frequently.

KKR’s Seeger believes an emphasis on environmental, social and governance factors can deliver returns and cut company costs, but she concurs with some others that it’s tough to quantify the results. “What we’re not able to do is put a single number on that,” she said, referring to the returns stemming from ESG attention. “A lot of that is risk mitigation, which is hard to measure.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.