Proteus Syndrome: 'Elephant Man' Gene Mutation Identified, May be Treatable, Study Says

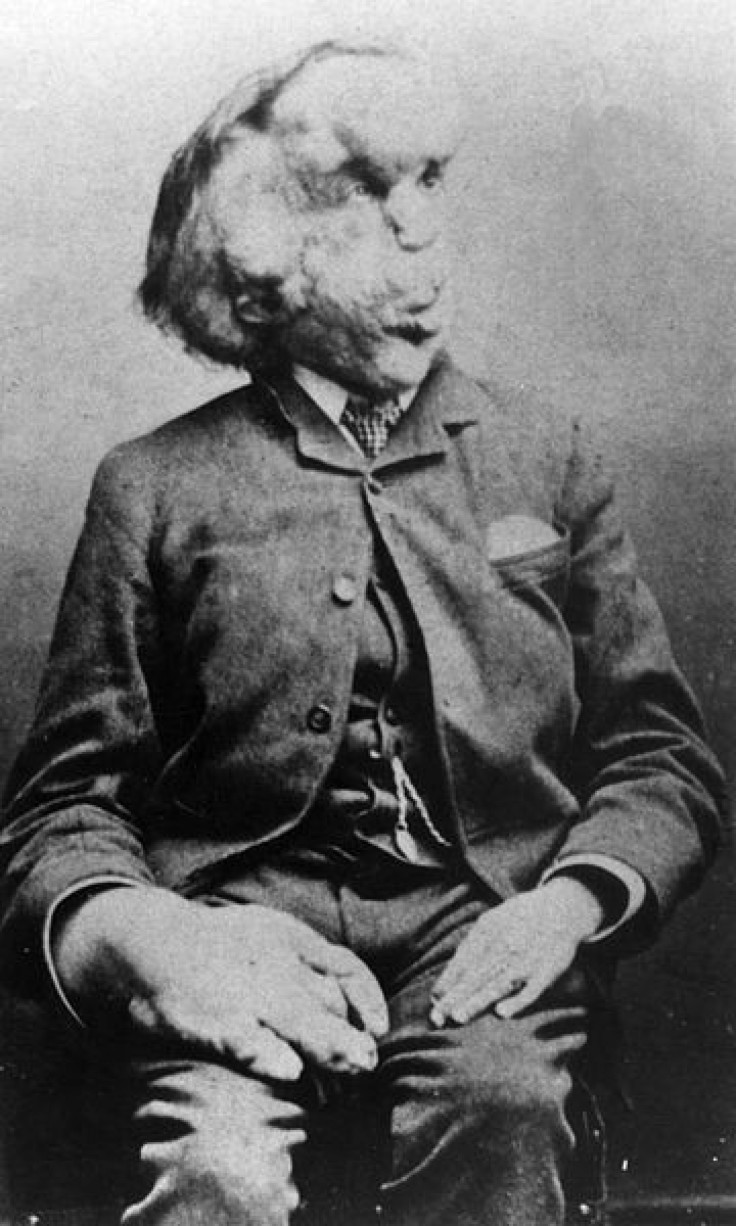

A single gene mutation believed to be responsible for the disfiguration of the "Elephant Man," who toured Europe in the 19th century and was the subject of a 1980 film, is believed to have been found by scientists.

The gene, which is also linked to cancer, may now be treatable with drugs now in development, the researchers said, Bloomberg reported. Proteus syndrome, named for the shape-shifting Greek sea god, is marked by uncontrolled tissue and bone growth. It affects fewer than 500 people worldwide, according to the National Institutes of Health.

As a result of Proteus syndrome, skin and other tissues grow abnormally, leading to enlarged hands, feet and (sometimes painful) tumors.

Leslie Biesecker, the senior author of the report published Thursday in the New England Journal of Medicine, said the single mutation is basically one misspelling among 3 billion letters that make up the human genome. It isn't inherited, she said, and it occurs during fetal development.

"All patients so far have exactly the same mutation in the same gene, and it's never found in unaffected people," Biesecker said, who is the chief of genetic diseases research at the National Human Genome Research Institute. "Once the mutation happens, the cells that descend from that mutated cell display uncontrolled growth that characterizes the disorder."

Researchers said they intend to analyze the remains of Joseph Merrick, known as the "Elephant Man," to confirm their findings and diagnosis. Merrick died in 1890 in London.

The scientists found the cells that were unaffected by the mutation continue to develop, giving the affected child two separate genomes. For doctors to properly diagnose has been difficult, Biesecker said, as, in some cases, only the normal cells were studied.

So Biesecker's research team utilized a strategy that uses next-generation DNA sequencing to decode all the genome's protein-coding DNA, known as the "exome." Sequencing the exomes of the abnormal and normal tissues from seven Proteus patient's bodies, the team compared them with healthy people's exomes to ferret out the culprit gene.

All of the Proteus patients shared the same single-base mutation in a gene called AKT1.

After testing 22 more patients, they found the mutation in 26 of the 29 tested. The remaining three could have the mutation at lower levels or different tissues, the researchers said.

For their analysis, researchers used tissue removed during surger to control excessive bone and tissue growth during the past 15 years, said Eric Green, director of the National Human Genome Research Institute. The process, he said, took time because they needed the technology to mature.

"We are just starting to capitalize on the leading edge of this genomic revolution, "he said. "Like X-rays that peered into our bodies in the previous century, the power to routinely and robustly peer into our genomes will prove revoltutionary."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.