Quasars May Have Killed Star Formation In The Earliest Massive Galaxies

Quasars, the brightest objects in the universe, may have been responsible for the stopping of star-formation activity in some of the early massive galaxies in the universe, a new study suggests. These galaxies were hotspots of activity, throwing up stars by the billions, about 12 billion years ago, but are now mostly astral dead zones.

Called dusty starburst galaxies, they are among the biggest and oldest galaxies there are. And as is the case with all galaxies, they are believed to contain at their centers' quasars and supermassive black holes. It was spotting quasars inside four starburst galaxies that are still producing stars — using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array of radio telescopes in Chile — that led the astronomers behind the new study to reach their conclusion.

Hai Fu, an assistant professor at the University of Iowa and first author of the paper describing the team’s findings, said in a statement Monday: “These quasars may play an important role in making the dusty starbursts extinct in the cosmic history. This is because quasars are energetic enough to eject gas out of the galaxy, and gas is the fuel for star formation, so quasars provide a viable mechanism to explain the transition between a starburst and an extinct elliptical (galaxy).”

Read: Extremely Red Quasars Suppress Star Formation In Their Host Galaxies

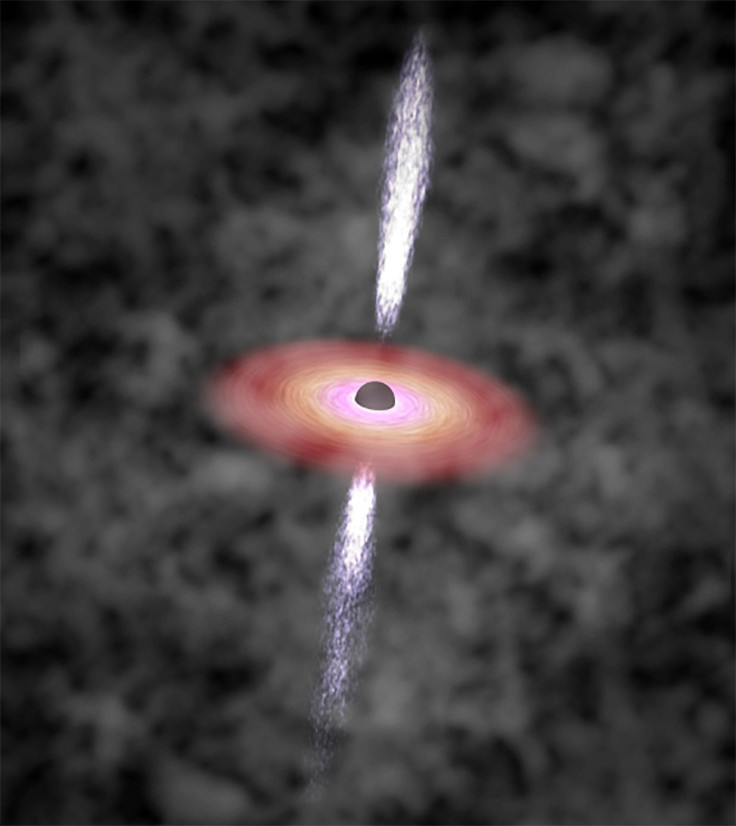

The very high luminosity of quasars, enough to outshine their host galaxies, comes from the fact that they emit radiation across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, which is due to the energy released when gas from the accretion disk around a supermassive black hole (quasars consist of a supermassive black hole and an accretion disk) falls onto the black hole. The most powerful quasars are thousands of times more luminous than a large galaxy like our own, the Milky Way.

Quasars are also incredibly far away, with the farthest known quasar detected from a time when the universe was only about 770 million years old. The large distances make them difficult to spot, despite their luminosity. And when we take into account absorption and scattering of light by the dust in a star-forming dusty starburst galaxy, quasars inside them shouldn’t be detectable at all, according to Fu.

“So, the fact that we saw any such quasars implies that there must be more quasars hidden in dusty starbursts. To push this to the extreme, maybe every dusty starburst galaxy hosts a quasar and we just cannot see the quasars,” Fu said.

The fact that the quasars within these four galaxies were visible to the researchers raised questions about how they could see what should not have been visible. They theorized that each of the four galaxies has deep holes — columns of vacuum with no debris and dust — through which the quasars can be seen. The researchers also imagine the galaxies to be donut-shaped.

“It’s a rare case of geometry lining up. And that hole happens to be aligned with our line of sight,” Jacob Isbell, a senior at the university and the paper’s second author, said in the statement.

Read: Quasars With Unexpected Halos Found

Researchers from other universities around the country, including University of Texas at Austin, University of California, Irvine, University of California, Santa Cruz, California Institute of Technology, and the University of Hawaii, participated in the research. The paper, titled “The circumgalactic medium of submillimeter galaxies. II. Unobscured QSOS within dusty starbursts and QSO sightlines with impact parameters below 100 kiloparsecs,” appeared in the Astrophysical Journal.

A previous study that appeared in November 2016 also showed that quasars can suppress the formation of stars within the galaxies they inhabit. This would happen when the energy from the quasar heats up the gas and dust that could have formed stars at cooler temperatures.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.