Ravi Shankar: The Accidental Superstar

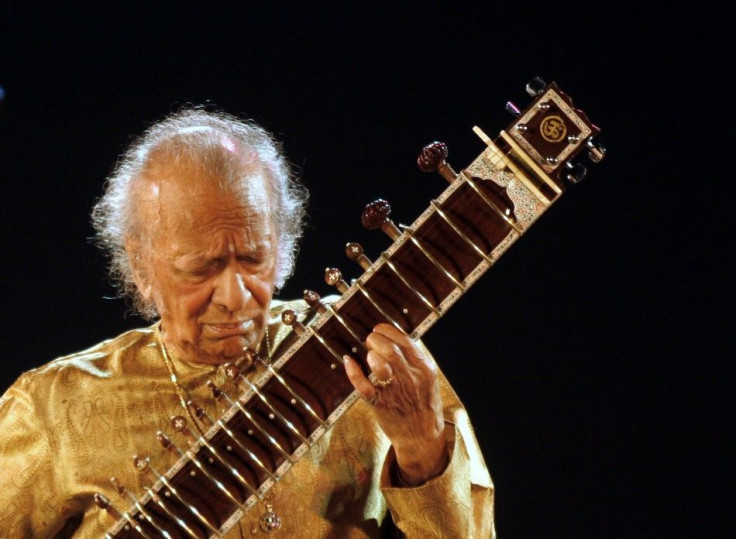

Ravi Shankar, the Indian sitar virtuoso, has died at the age of 92, ending a long, epic and highly improbable life and career.

When he was born to a privileged Bengali Brahmin family (his father was a British-educated lawyer and international traveler) during the height of the "Raj" Empire in India, Ravi’s elder brother, Uday, was actually the Shankar brother destined for greatness. Uday was a renowned Indian classical dancer who toured the world during the 1920s and 1930s.

However, by the mid-1960s, after he had enjoyed tremendous acclaim as a highly accomplished composer and classical sitarist for 30 years (known only to devotees of the music style in India and a tiny handful of Westerners), Ravi attained a level of global fame his brother could not have even dreamed of.

Sometime in either 1965 or 1966 in London, Ravi Shankar met a long-haired young Irish-Englishman named George Harrison, who happened to be the lead guitarist of the most popular and successful pop music group the world has ever seen -- The Beatles.

Shankar taught Harrison how to play sitar and became his close friend and confidant, which, in turn, inspired the wealthy rock star to explore Indian culture and Hindu spirituality – which led, in turn, to an “earthquake” of sorts in Britain, Europe and America.

“I never thought our meeting would cause such an explosion, that Indian music would suddenly appear on the pop scene,” Shankar once said.

Shankar’s relationship with Harrison inadvertently made the homely, little Bengali man with the reedy voice and heavy accent an international superstar -- and it placed him in venues where no Indian sitarist had ever performed before.

Among other things, Shankar played classical Indian music to an audience of drug-addled hippies at the Monterey Pop festival in 1967, the Woodstock festival in 1969 and the Concert for Bangladesh in 1971.

Through the enormous influence of Harrison, sitars and Indian raga-style music found a home in records by popular Western stars, including the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Animals and many others.

Alas, the encounter between East and West was never smooth and seamless.

While Shankar was obviously excited about the opportunity to introduce his ancient musical form to millions of young Westerners who otherwise would never have been so exposed, he was disturbed by such "Western" practices as drug-taking, tobacco-smoking, alcohol-imbibing and sexual promiscuity, traits that clearly would put him at odds with the customs of the rock star lifestyle.

Still, Shankar (who became the most famous and most recognizable Indian in the world) must have been intoxicated by the atmosphere of wealth and licentiousness that George Harrison introduced him to. In fact, like his Western counterparts, Shankar had quite a messy personal life, having many affairs with various women.

In response, many Indian admirers were appalled by Shankar’s flirtation with Western rock stars -- something even he admitted.

“I do think that my Indian classical audiences thought I was sacrificing them through working with George,” Shankar once said.

“I became known as the ‘fifth Beatle’; in India, they thought I was mad.”

In 1981, he told an interviewer: “In India I have been called a destroyer. But that is only because they mixed my identity as a performer and as a composer. As a composer I have tried everything, even electronic music and avant-garde. But as a performer I am, believe me, getting more classical and more orthodox, jealously protecting the heritage that I have learned.”

Indeed, during the 1971 Concert for Bangladesh in Madison Square Garden, prior to performing a series of Indian classical pieces with renowned tabla player Alla Rakha and sarod virtuoso Ali Akbar Khan, Shankar asked the audience to be quiet and to “refrain from smoking.” (Has such an entreaty ever been made at any other rock concert?)

Shankar himself wisely realized that he was treated as an oddity and an exotic intruder by most Western rock fans.

“On one hand,” he said in 1985, “I was lucky to have been there at a time when society was changing. And although much of the hippie movement seemed superficial, there was also a lot of sincerity in it, and a tremendous amount of energy. What disturbed me, though, was the use of drugs and the mixing of drugs with our music. And I was hurt by the idea that our classical music was treated as a fad -- something that is very common in Western countries.”

He bitterly added: “People would come to my concerts stoned, and they would sit in the audience drinking Coke and making out with their girlfriends. I found it very humiliating, and there were many times I picked up my sitar and walked away. I tried to make the young people sit properly and listen. I assured them that if they wanted to be high, I could make them feel high through the music, without drugs, if they’d only give me a chance. It was a terrible experience at the time.”

His alliance with George Harrison sealed his worldwide fame, but Shankar also collaborated with such notable musicians as violinist Yehudi Menuhin, flautist Jean-Pierre Rampal and jazz saxophonist and composer John Coltrane (who even named his son Ravi).

However, ultimately, Shankar’s fame and legacy lies squarely with his links to George Harrison -- a relationship he was rather ambivalent about.

“I wonder how much they [Western music fans] can understand, and where all this will lead to. There is so much in our music that goes back thousands of years,” he said in 1971.

“It is strange to see pop musicians with sitars. I was confused at first. It had so little to do with our classical music. When George Harrison came to me, I didn’t know what to think. But I found he really wanted to learn. I never thought our meeting would cause such an explosion, that Indian music would suddenly appear on the pop scene.”

In 2009, Shankar even conceded: “When people say that George Harrison made me famous, that is true in a way.”

In an American television interview from 1979, Harrison discussed his first exposure to Indian sitar music.

“I listened to it, and although my intellect didn’t really know what was happening, or didn’t know much about the music, just the pure sound of it and what it was playing, it just appealed to me so much,” he said.

“It hit a spot in me very deep, and it was, you know I just recognized it somehow. And along with that I just had a feeling that I was going to meet him [Ravi] ... I wanted something better, I remember thinking, I’d love to meet somebody who will really impress me, and that’s when I met Ravi. Which is funny, cause he’s this little fella with this obscure instrument, from our point of view, and yet it led me into such depths. And I think that’s the most important thing, it still is for me.”

Thus, Harrison’s devotion to Indian music and culture was indeed genuine; however, for Ravi Shankar, that historic link to the Beatle created a mixed legacy.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.