Retina Scanners And Biometric Passports: A Look At The Futuristic Tech That Could Scan Refugees

Nearly two weeks after seven terrorists massacred 130 people and wounded hundreds more on the streets of Paris, President Barack Obama stood beside French President François Hollande on Tuesday and said the government was developing "biometric information and other technologies that can make [scanning refugees] more accurate."

As International Business Times reported this week, refugees are already subject to an exhaustive vetting system that includes a series of verbal and in-person interviews with American security officials and usually takes 18 to 24 months.

So what exactly was Obama talking about when he referenced an expansion of “biometric technologies”?

As European and American politicians grapple with how to screen refugees for potential terrorist links, many governments are looking for smarter tech to monitor and verify a person’s identity as they cross borders. Much of this technology already exists, but because it’s expensive, cash-strapped European countries have yet to make serious investments. That may change in the coming months.

A Boom In Bio-Passports?

Stefan Lofven, Sweden’s prime minister, proposed last week the introduction of biometric passports, or “ePassports.” Biometric passports have been around for a few years but their use is gaining traction in the wake of looming terror threats.

These high-tech identification cards are embedded with a “smart card” that contains information like fingerprint and facial scans, which help authenticate its holder’s identity. It’s the same kind of chip that’s used in contactless smart cards or credit cards that allow for the wireless transfer of data. According to the State Department, there are about 490 million ePassports in circulation. That number will likely grow in the coming years.

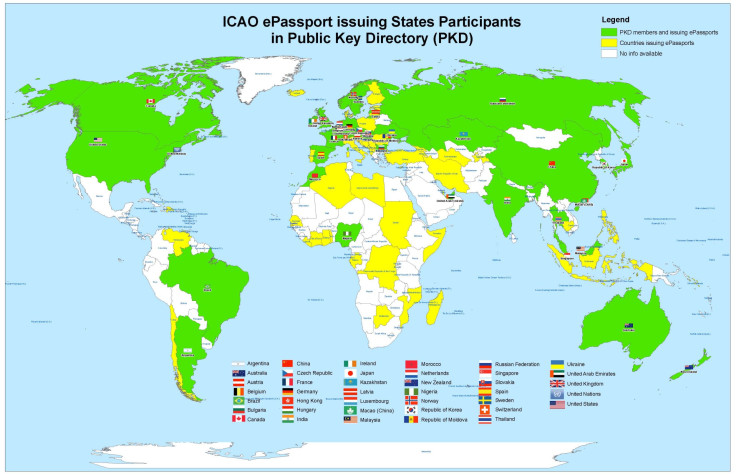

IHS Technology, a global research firm headquartered in New York, estimates ePassport shipments could reach 180 million per year by 2019. According to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), 93 out of 193 U.N. member states already issue ePassports, even if only a small percentage of the country's population actually have them. India and Japan, ICAO says, are growing their ePassport programs at the fastest rates.

But the tech is advancing beyond smart passports. Perhaps the most interesting development is the use of eye scanners along borders. Similar to a fingerprint, a person’s iris contains completely unique information, making it an ideal source of biometric information that can’t be faked.

IrisGuard, a London company that manufactures the EyeGuard AD100, already works with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to collect information on Syrian refugees.

The way it works is fairly simple: A user looks into the binocular-like device, which takes an image of the iris and converts it into a unique digital code. That code is then stored on a database housed within the UNHCR office for later rapid matching. Combined with extensive in-person interviews and cross-referencing other documents, a person’s iris biometric data is then entered into a database.

In June, IrisGuard announced it had collected 1.6 million eye scans from Syrian refugees. “This enables the agency to instantly execute cross-country operational transactions within a few seconds, regardless of where the refugee is located," the UNHCR noted on its blog.

The market around iris-scanning, in fact, is clearly on the rise, even if it’s not yet in full swing. In November, Frost & Sullivan, a research firm, found that the iris-scanning market earned revenues of $142.9 million in 2014 and estimates the market will reach $167.9 million by 2019.

Eye-Catching Tech Is Still In Early Phases

Robert Haddon, the security research analyst for Frost & Sullivan's aerospace and defense team, cautioned that though iris-scanning may increasingly be used for border control, it’s not yet a foolproof system. “The major drawback with iris technology at the moment is connected to the cost and the relatively small amount of iris data that authorities are likely to have on potential terrorist suspects,” Haddon said.

He added, “The real challenge for law enforcement will be in sharing this information whilst also being sensitive to data protection and transference regulations that are already in place.”

Despite the fact that none of the Paris attackers have been actually labeled a Syrian refugee, politicians across Europe and North America have begun pushing for tighter border controls and harsher restrictions for refugees and migrants. Republican presidential candidates Donald Trump, Ben Carson and Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida -- along with 31 state governors -- have sought to ban Syrian refugees altogether.

Meanwhile, some European governments, like Poland, have moved to shut their doors as well. “After Paris, we lost security guarantees,” Konrad Szymanski, Poland’s new minister for European affairs, said last week.

These sentiments will likely fuel an investment in border control technology that is already rapidly growing. According to Visiongain, a London research firm, the global border security market will generate $16.4 billion in revenue in 2015, and that number is likely to grow. It’s not just biometrics, though. Manned and unmanned vehicles, drones and digital tracking technology will also experience a surge.

Still, despite all the new high-tech advances in eye scans and futuristic passports, it may be old-school fingerprinting that sees the biggest growth. Robert Haddon, the Frost & Sullivan analyst, says that because there’s already such a large database of fingerprints, border control agents and law enforcement departments may shy away from “specialist” technology like iris scanners.

“The fact that fingerprint systems are so widely used by law enforcement authorities and that facial recognition software can be deployed onto existing camera systems without the need for specialist technology make them a much more likely fit to see investment increases,” Haddon said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.