River Flow On Saturn Moon Titan More Like Mars Than Earth

Titan is the only place in our solar system where liquid currently flows in the same way it does on Earth, but it turns out that this moon of Saturn may have more in common with Mars than with our planet.

Recent research suggests while Earth’s landscape was formed more by collisions beneath its surface, with tectonic plates crashing to form mountains and influence the path of rivers, rivers on Titan and the traces of ancient rivers on Mars did not show signs of the same processes.

A study in the journal Science reported analyzing those river patterns leads scientists to “long-wavelength topography on Titan and Mars,” referring to processes like, in the case of the icy Titan, tidal pull from its mother planet Saturn causing changes in the thickness of its crust rather than tectonic plate activity within the crust itself. The topography is not in constant flux the way it is on Earth, where rivers can be diverted.

Read: Spacecraft Records What Saturn Sounds Like

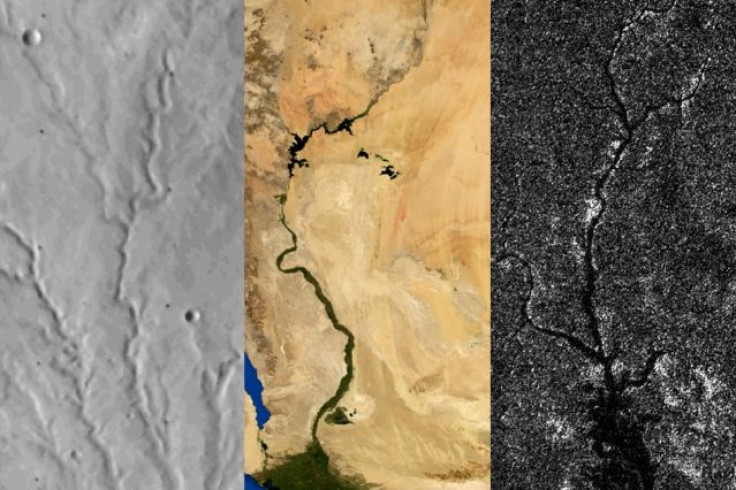

For the Titan observations, the researchers used information sent back from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, which has been hanging out near Titan, Saturn and the planet’s other moons for several years. River map data already existed for Earth and Mars, and they compared the features of rivers on the different worlds, including their slope and the direction of their flow. With Mars and Titan, but not with Earth, details of those rivers did not show tectonic plate activity in its recent past, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology said.

“While the processes that created Titan’s topography are still enigmatic, this rules out some of the mechanisms we’re most familiar with on Earth,” lead author Benjamin Black said in the MIT statement.

That could be a bit of a bummer for people who are rooting for Titan as a candidate for human exploration or even as a host for alien life. Although the liquid flowing on its surface and raining from the sky is methane rather than water, it has been a point of interest for space enthusiasts because in addition to being the only moon with dense clouds and atmosphere, it is the only place in the solar system other than Earth where liquid flows in that way — at least in modern times. There is evidence liquid once flowed on the surface of Mars.

In fact, recent research suggests at a certain time in Martian history, including when it still had a thick atmosphere that had yet to be lost to outer space, rain fell heavily. That rain would have been strong enough to erode craters and saturate the soil, eventually flowing into rivers that left valleys or channel-like marks on its surface when they dried up. Those marks say a lot about the conditions on the planet while the water was flowing, even if they have since changed or disappeared: “Rivers erode the landscape, leaving behind signatures that depend on whether the surface topography was in place before, during, or after the period of liquid flow,” the study said.

Read: Here’s What It’s Like to Build Sand Castles on Titan

Regardless of how similar to or different from each other Titan and Earth are, the study provides clues about how the pieces of our solar system developed over time. “There’s this amazing opportunity to use the landforms the rivers have created to learn how the histories of these worlds are different,” researcher and MIT geology Professor Taylor Perron said in the university’s statement.

The river comparison suggests Martian topography was already fairly solidified before the rivers started flowing and that largely influenced the way the water moved, despite later asteroid impacts and volcanic eruptions.

“We know something about rivers, and something about topography, and we expect that rivers are interacting with topography as it evolves,” Black said. “Our goal was to use those pieces to crack the code of what formed the topography in the first place.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.