Rodent-like Vegan Mammals Thrived with Dinosaurs: Study

For decades, researchers believed that mammals could not have thrived until the dinosaurs went extinct. Recent research, however, conducted by evolutionary biologist Dr. Alistair Evans, of Monash University in Melbourne, and colleagues, tends to suggest otherwise. The new study indicates that at least one group of ancient mammals thrived and started expanding 20 million years before the dinosaurs died.

A closer look at ancient mammal teeth suggests that mammals were able to expand because they discovered a food source not consumed by others, and not because the dinosaur extinction made room for them. When the dinosaurs went extinct 65 million years ago, these mammals continued to prosper.

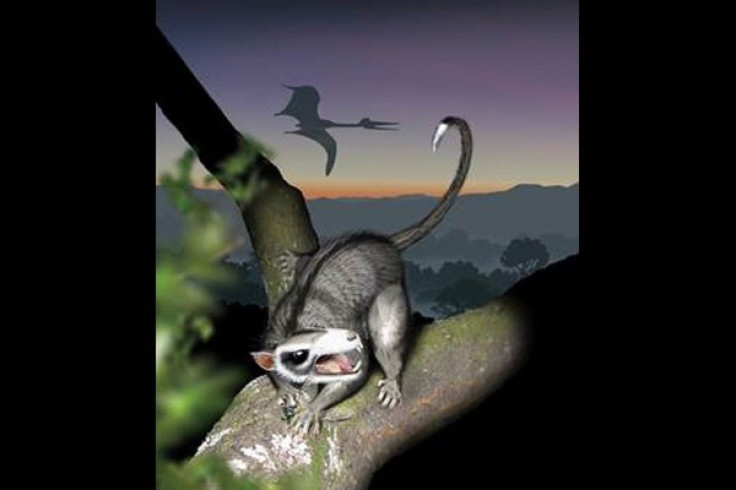

The most common mammals before dinosaurs disappeared off the face of the earth, were multituberculates, named after their teeth. “Many of the tuberculates have very bumpy teeth and each of the bumps is called a tuberculate,” said Evans. Multituberculates managed to thrive partly because they developed numerous tubercules on their back teeth, allowing them to feed largely on angiosperms. “These mammals were able to radiate in terms of numbers of species, body size and shapes of their teeth, which influenced what they ate,” said UW paleontologist Gregory Wilson, the lead author of a paper documenting the research.

About 170 million years ago, these multituberculates were roughly the size of a mouse, but when angiosperms started to appear some 140 million years ago, the small mammals increased in body size, eventually reaching the size of a beaver.

Tapping fossil collections worldwide, scientists examined teeth from 41 multituberculate species. Using laser and CT – computer tomography – scans they created high resolution 3-D images of the teeth. Some multituberculates developed very complex teeth in the back of the mouth, with as many as 348 tubercules per teeth row, which made them ideal for crushing plant material such as angiosperms. Meanwhile, the teeth toward the front of the mouth were less prominent, but sharp and blade-like.

“If you look at the complexity of teeth, it will tell you information about the diet. Multituberculates seem to be developing more cusps on their back teeth, and the blade-like tooth at the front is becoming less important as they develop these bumps to break down plant material,” added Wilson.

Multituberculates continued to thrive long after the dinosaur extinction, but other mammals, particularly primates, ungulates and rodents, gained advantage and ultimately drove multituberculates extinct about 34 million years ago.

(reported by Alexanadra Burlacu, edited by Surojit Chatterjee)

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.