Rwanda Genocide Tribunal Passes Final Judgment, But Fugitive Suspects Remain

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda passed its final judgment on Wednesday, sentencing one last perpetrator of the 1994 Rwandan genocide to 35 years in prison. But nine of the court’s indicted suspects remain at large, so the search for justice will be far from over when the judicial facility -- located in Arusha, Tanzania -- closes its doors.

The tribunal was set up by the United Nations Security Council in 1994, the same year that hundreds of thousands of Rwandan civilians lost their lives in one of the worst tragedies of modern history. The spring genocide lasted only about 100 days – but by the end of the bloodshed, 800,000 men, women and children had lost their lives.

The struggle was defined in ethnic terms: Hutus who dominated the government at that time condoned, if not directed, the systematic killing of Tutsi civilians across the country. But many moderate Hutus were also murdered, and militants of both ethnicities were involved in the violence. Politics played a major role, especially since the Hutu regime was fighting a rebel army of exiled Tutsis, who now run the country.

On Wednesday, the court convicted Augustin Ngirabatware, 55, of directing Hutus in the northwestern district of Nyamyumba to kill Tutsis. As a minister of planning, he also distributed weapons – mostly machetes – to the militants.

Ngirabatware was sentenced to 35 years in prison. He is the 63rd defendant to be convicted since the Arusha court’s first judgment was passed in 1998. The tribunal will close down permanently in 2014, after attending to 15 appeals that remain.

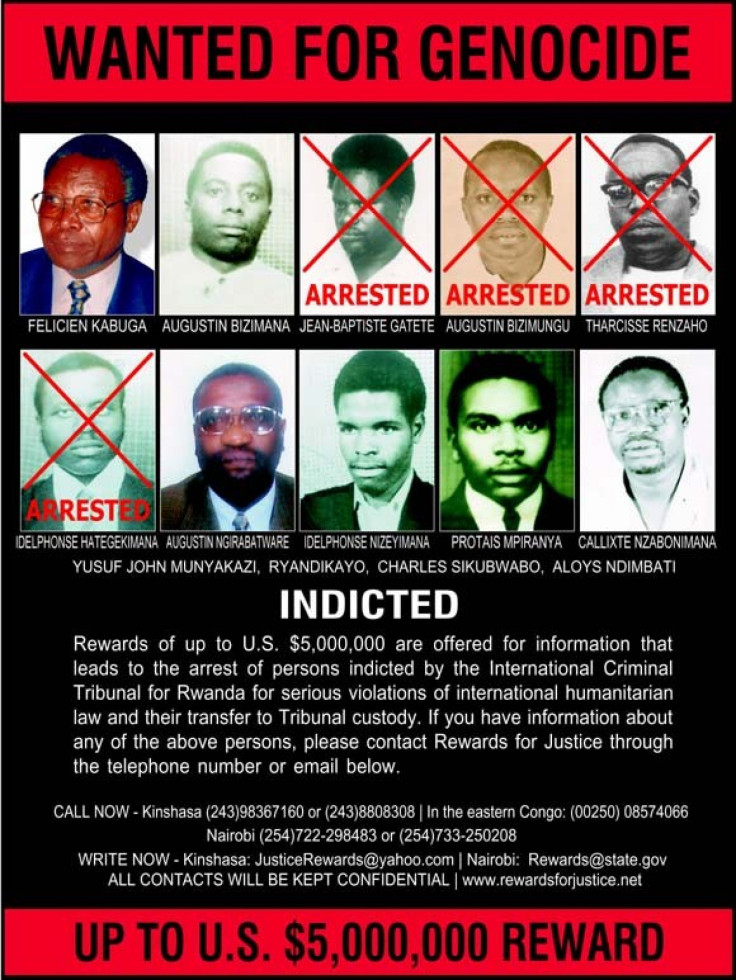

Of the nine suspects who have not yet been apprehended, the most notorious is Felicien Kabuga, a wealthy businessman who is accused of bankrolling the genocide and helping to import hundreds of thousands of machetes into the country.

Other suspected top perpetrators still at large include Protais Mpiranya, who headed the presidential guard; and Augustin Bizimana, a former minister of defense.

Those three would be tried by a U.N. court in the event of their capture. The other six at large would be handed over to Rwandan authorities.

In the meantime, the people of Rwanda will continue to deal with the legacy of violence that tore their country apart 18 years ago. The government that ascended to power after the genocide was – and is – dominated primarily by the Tutsi minority, though ethnic differences are a forbidden subject these days. With help from international aid funding, most of which comes from the United States, President Paul Kagame has presided over a period of impressive economic development.

But Kagame’s administration has also been accused of suppressing dissent and committing human rights violations. In October of this year, opposition leader Victoire Ingabire was sentenced to prison for divisive speech: She had suggested that the peaceful Hutus who were massacred during the genocide be memorialized alongside Tutsis.

Clearly, Rwanda has a long way to go before old wounds can heal. But justice, even if meted out by an international tribunal in Tanzania, is a positive step in that direction.

Justice Hassan Bubacar Jallow, the chief prosecutor in Ngirabatware’s case, said in a statement that the Arusha tribunal had served its purpose admirably.

“The delivery of judgment today in this case marks a historic occasion and important milestone in the work of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.