Scientists Figure Out How DEET Makes Bugs Buzz Off, And How To Make Safer, Cheaper Alternatives

Scientists think they’ve discovered the secret to how the insect repellent DEET works -- and with it, the secret to making a cheaper, safer alternative.

DEET, also known as N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide, was developed by the U.S. Army in the 1940s. It's an effective insect repellent, but is also slightly toxic. DEET can dissolve some plastics and nylon, and there's some evidence that it can interfere with an enzyme called acetylcholinesterase that’s active in the mammalian nervous system. While the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency doesn't believe that DEET presents a general health concern, there are some cases where the chemical has been implicated in seizures in children. According to Cornell University’s Pesticide Information Profile, workers at Everglades National Park with higher levels of DEET exposure were more likely to have insomnia, disturbed moods and impaired cognitive functions.

Plus, DEET is costly, making it impractical for use in Africa and other developing nations that are plagued by disease-carrying insects. Thus, finding a cheaper, safer alternative to DEET would be a boon for world health.

But one of the bigger challenges to finding DEET alternatives was that scientists didn’t know exactly where the chemical was triggering a bug’s smell receptors. Now University of California Riverside entomologist Anandasankar Ray and colleagues say they’ve solved the smelling puzzle, and have already discovered some compounds that might make bugs buzz off just as well as DEET. They laid out their work in a paper published in the journal Nature on Wednesday.

Ray and colleagues tracked DEET sensitivity in fruit flies back to a pit-like structure of the antenna called the sacculus.

"It's difficult to study this organ," Ray said in a phone interview. It's hard to stick the electrodes in the antenna just so to hit the sacculus, "and perhaps this is one of the reasons why scientists have had trouble finding the DEET receptor for many years."

Neurons in the sacculus contain a receptor called Ir40a. When this receptor is knocked out through genetic engineering, the flies stop avoiding the smell of DEET. Furthermore, Ir40a crops up in a wide range of insect species, including fruit flies, mosquitoes, head lice and flour beetles -- but not honeybees, according to the paper.

It's still not entirely certain what about DEET and the activation of Ir40a is so unpalatable to insects. Ray guesses DEET and similar compounds just smell nasty to bugs. But the behavior is clear -- if something smells like DEET, most insects avoid it.

Now that the researchers knew what receptor was important, they scanned a database of more than 400,000 compounds to find ones that might activate Ir40a. Of the more than 100 candidates, the researchers settled on four finalists that were able to ward off both fruit flies and mosquitoes.

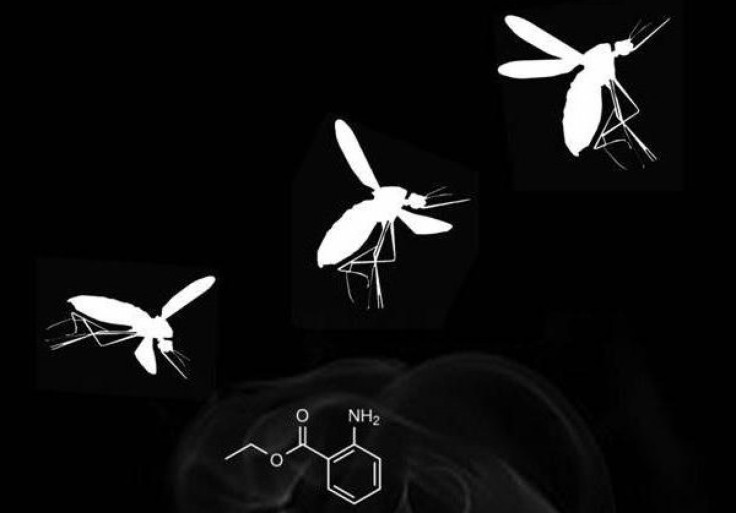

Three of the four compounds (methyl N, N-dimethyl anthranilate, ethyl anthranilate and butyl anthranilate) are approved for human consumption by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and are already used to flavor some foods. They have a mild, fruity smell similar to grapes. Ray and his team are already working on making new commercial insect repellents that could be used to repel mosquitoes, flies, and possibly other insects including bedbugs, ants, and cockroaches.

"Our findings could lead to a new generation of cheap, affordable repellents that could protect humans, animals and, in the future, our crops as well," Ray said.

It may be possible to find a compound that could activate Ir40a that is both safe for human consumption and easy to spray on crops. And agricultural pests are a worldwide scourge on par with mosquitoes.

"30 to 40 percent of agricultural produce is destroyed by insects, so we're speaking of billions of dollars of loss and hardship for farmers" that could be mitigated, Ray says.

SOURCE: Kain et al. “Odour receptors and neurons for DEET and new insect repellents.” Nature published online 2 October 2013.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.