Scientists Spin Ultralight ‘Cotton Candy’ Carbon Nanotube Electrical Wiring [VIDEO]

Research scientists at the University of Cambridge have developed electrical wiring from carbon nanotubes that is much longer than ever before. They developed a system where the wire is “spun” from a reactor that looks like cotton candy, allowing the researchers to make carbon nanotubes into usable lengths for the first time.

The carbon nanotubes, or CNTs, are one-tenth the weight of the same length of copper, and 30 times stronger. CNTs are a series of hollow tubes made up of carbon atoms. The researchers have also developed a way for the carbon nanotubes to be easily joined with metals, to create hybrid networks as the material is rolled out into electrical systems.

“It is reasonably simple for us to make a meter-long wire made of carbon and use it in an electrical system,” said Dr. Krzysztof Koziol of Cambridge, in a press release. “No longer are we talking about millimeter-long, minute samples.”

The researchers say their nanotubes will start by making more fuel-efficient, lighter satellites and airplanes, and could eventually be used to do the same in automobiles. A large satellite derives a third of its 15-ton weight from electrical wiring, which the researchers say would be greatly reduced by using the carbon nanotubes, which are about one-tenth the width of the human hair.

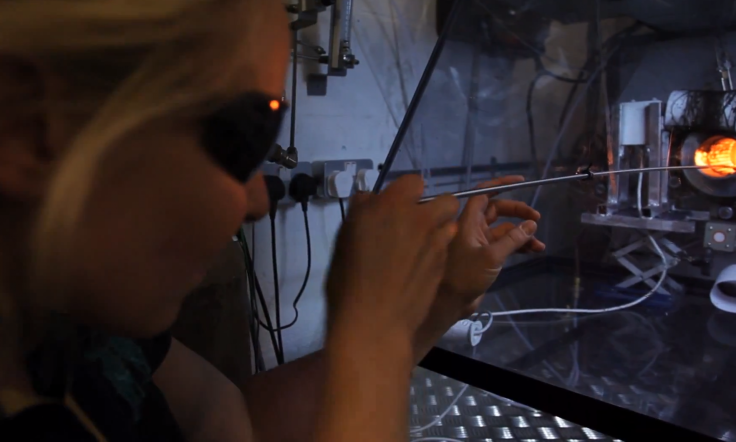

The process resembles the spinning of cotton candy onto a paper cone. IBTimes spoke with Koziol about how the process is completed.

"We make CNTs by cracking hydrocarbons like methane and form millions or even billions of CNTs in a high-temperature furnace. These CNTs take the form of an aerogel, which looks like cotton candy," Koziol said. "Once the aerogel has formed, we simply pull it out from the other end of the furnace."

Koziol said the pulling causes the CNTs to come together into a fiber, due to a force known as the van der Waal reaction that holds them together.

"We take the fibers and twist them together into yarns of any diameter we wish. Once these yarns are insulated, they can be used as electrical wiring," he said.

One hurdle to adopting carbon wiring, which is more resistant to corrosion and can carry a higher electrical current than copper, is joining it to standard electrical systems like those found on airplanes and houses. The solder used to join common metals contains a fair amount of tin, and will not bind to carbon nanotubes. The scientists found a way to bind the materials by developing a special solder that conducts electricity from carbon to copper wiring.

Since carbon nanotubes are made from raw materials that are much less precious than copper, they should cost less to produce. The copper used in electrical wiring has to be mined and physically and chemically purified to become highly conductive, all steps that consume energy.

"While there will be costs associated with scaling our technology up, the actual process of producing wiring from carbon is orders of magnitude less expensive because we form the nanotubes straight from gas, which is a byproduct of oil production," Koziol said. "We don't need to mine carbon."

Koziol said the researchers believe the cost of making carbon wiring is relatively low since the only major expense would be using iron, a more readily available element, as a catalyst.

Another hurdle for scientists is improving the conductivity of carbon wiring, which is made up of much smaller carbon nanotubes joined together. As each wire is connected to the next, the system loses conductivity. The wiring currently being developed by the team is still less conductive than copper.

Koziol and his team are working toward a more commercially viable version of the material that is at least as conductive as copper, and in the meantime are working on “a hybrid carbon-copper wire” that is lighter and stronger than current systems.

Follow Thomas Halleck on Twitter

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.