Shadow Banking Now Dominates The Mortgage Market, Edging Out Wall Street Giants

Ever since subprime mortgages helped torpedo the American financial system, a quiet revolution has taken place in the home loan industry. The handful of large banks that once dominated the field have steadily retreated from making mortgages, ceding their market share to so-called shadow banks, less tightly regulated lenders that hold no deposits on their books -- and the trend has lawmakers and regulators worried.

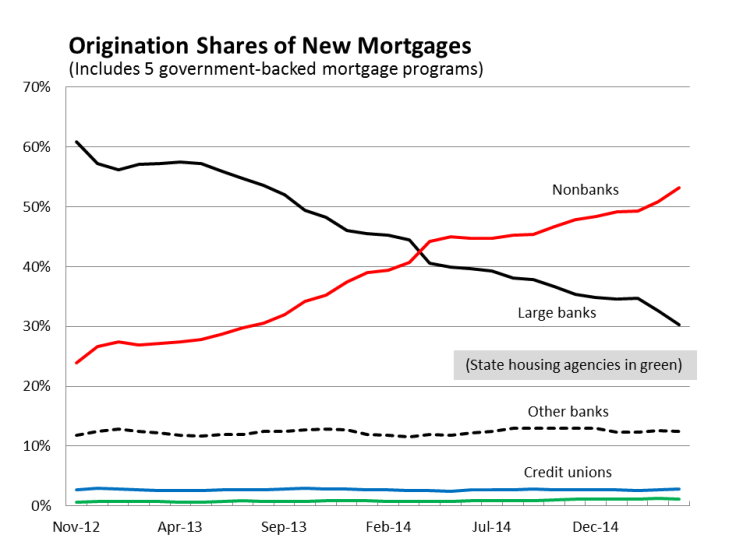

Now, for the first time, shadow banks capture the lion’s share of new government-backed mortgage origination. In April, lenders like loanDepot.com and mortgage stalwart Quicken Loans issued 53 percent of new home loans, edging out traditional banks and credit unions.

The share of government-insured mortgages coming from these companies has more than tripled since 2010, according to data from the conservative American Enterprise Institute. (Around 80 percent of home financing is now backed by some form of government insurance.)

That new reality has experts warning of an unprecedented new era in the mortgage industry, in which the majority of home loans come from institutions with no deposits on their books -- a massive transfer of systemic risk from closely scrutinized depository banks to lightly regulated shadow banks.

“This is a whole new era,” says Marshall Lux, co-author of a new study from the Harvard Kennedy School on the rise in nonbank mortgages. “It’s a night-and-day situation.”

While federally insured institutions like Bank of America and Wells Fargo make loans against their deposits, shadow banks generally use revolving lines of credit and investors’ cash to backstop their mortgages. Since they're not proper banks, the companies dodge daunting post-crisis regulations, particularly around capital buffers.

A growing chorus of lawmakers and academics have raised the alarm over the potential harm the shadow banking sector could visit upon government institutions in the case of a downturn. The Financial Stability Oversight Council, for example, recently warned of the “unforeseeable risks” that nonbanks pose to government-sponsored loan programs.

But it seems that borrowers haven’t noticed the seismic shift occurring underfoot. Customer ratings of nonbank lenders don’t differ greatly from those of traditional banks, thanks in large part to protections written into the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act.

And the misleading lending practices that defined the heady pre-crisis years are largely a thing of the past. Instead, new companies are streamlining the mortgage process, cutting down on paperwork and simplifying contracts. Nearly everyone agrees it’s a better time to be a borrower.

Still, the Harvard study authors note, borrowers with low credit scores have begun accounting for a disproportionate share of nonbank loans, recalling the first stirrings of the mid-2000s housing bubble.

“Nonbank financial institutions can come into being quickly and can do things with less oversight,” says Julia Gordon, who studies mortgage policy at the left-leaning Center for American Progress and was not affiliated with the study. “Having seen how that kind of lending has gone in the past, we should be vigilant in the future.”

Filling A Void

As the housing bubble of the mid-2000s grew, major Wall Street banks piled into the mortgage business. Wells Fargo, JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup all ran subprime units. Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers each pumped big profits out of their subprime-lending subsidiaries.

But these ill-fated efforts weren’t the only catalysts of the 2008 meltdown. Nonbank actors like Countrywide Financial and Ameriquest churned out hundreds of billions of dollars in subprime loans, which they often sold to investment banks. “It was like cats and dogs living together,” says Lux. “It was a mess.”

Among the landmark post-crisis reforms was the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which oversees mortgage lending. The agency, formed in 2011, defined “qualified mortgages” and pushed lenders seeking government backing to meet the standards.

Around the same time, new capital rules began forcing banks to keep fewer risky liabilities on their books in case of a downturn. Combined with aggressive enforcement actions over crisis-era misdeeds, the new regulations helped push big banks out of the home loan business.

In 2012, large banks originated nearly two-thirds of the loans backed by the Federal Housing Administration. In February of this year, that share had dropped to around 25 percent.

The pullback from big banks could have been a disaster for low-income borrowers looking to buy homes, the Harvard study’s authors say. But nonbanks have filled the void Wall Street left. “For people particularly who are qualified to seek mortgages, they are increasingly having to turn to a source of credit which is not dependent on deposits,” says Lux.

But fears that the nonbank boom could trigger a deterioration in standards haven’t been borne out. Gordon says that we have regulators to thank for that. “The growth of nonbank mortgage lending is one of the best arguments as to why we need the CFPB,” Gordon says.

Of course, the mortgage market is far from perfect. Lenders Nationstar and Ocwen, which specialize in buying up distressed loans, have racked up a considerable string of complaints, the latter having paid steep federal penalties. But excluding those two companies, mortgage customers these days are more likely to raise a fuss about large banks than their nonbank counterparts, according to data compiled by the Harvard authors.

“It’s a really interesting time to be in the market,” says Lux. “The only thing we have to watch for is that greed doesn’t come back in.”

Political Puzzle

The new mortgage market poses conundrums for politicians. Even as pricey subprime-era settlements and Dodd-Frank’s capital requirements have nudged banks out of the lending space, proponents of strict regulation are raising red flags around the increase in shadow banking.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, for instance, in an April speech flagged shadow banks’ short-term financing as a potential risk to the financial system. The same short-term lending systems that nonbanks use today, Warren said, seized up during the financial crisis and “spread the contagion across the financial system.”

But the alternative, some warn, is lower-income borrowers having an even harder time finding credit. “We’re going to have a lot of these conflicts between innovation and safety and soundness,” says Robert Greene, co-author of the study.

Though shadow banks don’t face the same scrutiny from the Federal Reserve as major banks do, they have felt regulatory pressure. The sector continually complains about CFPB oversight. And the Federal Housing Finance Agency in January laid out rules mandating basic capital requirements for lenders hoping to sell their loans to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which bundle loans into securities and insure investors against losses.

But the current state of affairs might not last long. Efforts are underway in the Senate to ease up on Dodd-Frank’s lending rules. A recent draft bill from Senate banking committee chairman Richard Shelby, R-Ala., would relax qualified mortgage standards for banks that agreed to hold the loans on their books.

Advocates of tough lending requirements have taken aim at the provision. Shelby’s bill, says Gordon, “would provide broad exemptions that really blow a hole in the Dodd-Frank protections.”

Whether the bill passes or not, policy makers will still have to grapple with the domination of nonbanks in the mortgage sector -- a result few would have foreseen in 2008.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.