Should Manhattan Project Sites Become A National Historical Park?

What do we do with our inconvenient histories? Do we bury them, or do we memorialize them as a way of learning and moving on? That is the question now in front of Congress, which must decide whether or not to create a Manhattan Project National Historical Park.

One of the most ambitious scientific and engineering projects of the 20th century, the $2.2 billion Manhattan Project, employed 130,000 workers and created a unique partnership between universities, the federal government and the private industry to harness the energy of the atom in less than three year’s time. Of course, it also resulted in the deaths of more than 200,000 Japanese citizens at the close of World War II in 1945.

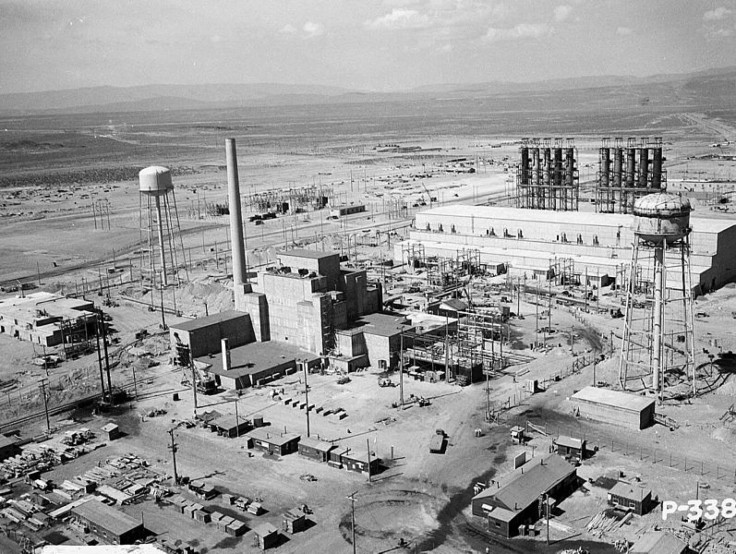

The new bill put before Congress would establish a historical park at sites in Oak Ridge, Tenn.; Los Alamos, N.M.; and Hanford, Wash. Senator Jeff Bingaman of New Mexico and Congressman Doc Hastings of Washington have led the charge, but it’s the Atomic Heritage Foundation that has been the driving force for the park’s creation over the past decade.

The Atomic Heritage Foundation claims the B Reactor at the Hanford Site, which was scheduled to be cocooned, attracted some 10,000 tourists over the summer from all 50 states and more than 60 countries amid relaxed rules on visitation. The Los Alamos National Laboratory, meanwhile, is in the process of restoring six of its Manhattan Project properties. At least two properties of significance in Oak Ridge, the Y-12 Beta-3 Calutrons and X-10 Graphite Reactor, would also remain for future generations under the proposed park. If it becomes a reality, the Department of Energy would have up to a year to think about how to create greater access to all of these facilities.

The Atomic Heritage Foundation has made establishing a national historic park its primary goal and has worked with Congress, the National Park Service, National Trust for Historic Preservation, National Parks Conservation Association, Energy Communities Alliance, local historical societies and Manhattan Project veterans to get the project off the ground.

Cindy Kelly, the foundation’s president, believes the Manhattan Project park could interest American youth in science and engineering by celebrating the innovators who harnessed atomic energy for the first time.

“In a broad sense, the Manhattan Project is a story of how science and technology have impacted history, economics, politics and society,” she said. “It’s something that those who have been schooled in humanities are less aware of. Those who are schooled in sciences, and who only focus on the science, often overlook the impacts. This Manhattan Project history shows very clearly the nexus of the realms of science and humanities and that we need, as a nation, to increase our science literacy.”

Very few people know how to connect the dots from the Manhattan Project through the Cold War to today, she said, and the park would help tell that story.

Some anti-nuclear groups fear that it would glorify the bomb, but Kelly said the interpretation by the National Park Service, or NPS, would incorporate diverse perspectives. Many other contested aspects of American history from Civil War battlegrounds to the Japanese-American internment camps, she noted, have navigated these same waters before and are now respected units of the NPS.

Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar agrees that the proposed park is a good fit for the NPS.

“The secret development of the atomic bomb in multiple locations across the United States is an important story and one of the most transformative events in our nation’s history,” Salazar said in a statement. “The Manhattan Project ushered in the atomic age, changed the role of the United States in the world community and set the stage for the Cold War.”

At the direction of Congress, the NPS conducted a special resource study on several proposed sites for possible inclusion in the National Park System. The study, released last year, recommended that the best way to preserve the sites was to establish a park.

“Once a tightly guarded secret, the story of the atomic bomb’s creation needs to be shared with this and future generations,” said NPS Director Jonathan B. Jarvis. “There is no better place to tell a story than where it happened, and that’s what national parks do. The National Park Service will be proud to interpret these Manhattan Project sites and unlock their stories in the years ahead.”

A bill to create the park, however, did not receive a two-thirds majority in the House and was defeated in September thanks to vocal critics like Congressman Dennis Kucinich of Ohio.

“The technology which created the bomb cannot be separated from the horror the bomb created,” he stated in opposition. “We should not celebrate the death of hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians or the destruction of two major Japanese cities no matter how proud we are of our ability to innovate.”

Kucinich argued that the park would cost taxpayers $21 million over five years.

Kelly countered that it would cost around $200 million to demolish the buildings and atomic sites and said she is “guardedly optimistic” that the park will have better luck with the Senate by the year’s end.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.