Silicon Valley Cops Want To Use 'Stingray' Cell Phone Surveillance Technology For Investigations

Police in Silicon Valley are eager to start using cell phone-tracking technology called "Stingray" for investigations. But county officials in Santa Clara, California, which includes much of Silicon Valley, are nervous the public doesn't know enough about the technology, which would be paid for by a grant from the Department of Homeland Security.

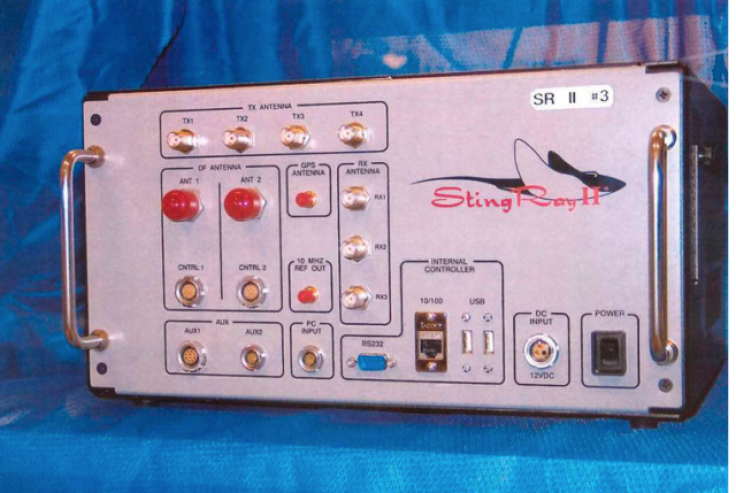

Santa Clara County Supervisor Joe Simitian complained that the sheriff's office is pressuring country officials to vote on authorizing use of the Stingray Tuesday, only days after the county was informed about the proposal's existence. The urgency comes as a federal grant for $500,000 from the Department of Homeland Security is set to expire, though Simitian told the Contra Costa Times the offer has been on the table for nearly a year. He's now calling for more input from the public on Stingrays, a suitcase-sized machine that, by mimicking a cell tower signal, is capable of sweeping up information on every cell phone that connects to it.

“I really don't think 15 minutes' worth of conversation on Tuesday is going to be enough,” Simitian told the local newspaper. “I'm a little disappointed if they're trying to hurry this up because the grant is going to expire. It would have been nice to have been told about this a year ago.”

The DHS has made it possible for law enforcement agencies of various sizes throughout the country to purchase and use Stingray technology while attracting little notice from the public. Stingrays, once only used for terrorism investigations, make it possible for police looking for a single cell phone to collect location data, text messages, billing information, phone call metadata and other sensitive information about potentially thousands of phones in the same area. Federal and local police are often required to sign nondisclosure agreements with Stingray manufacturers in order to obtain them, much to the chagrin of the American Civil Liberties Union, Electronic Frontier Foundation and other privacy advocates.

A spokesman for the Santa Clara sheriff's department told the Contra Costa Times that the police “tried to do the best we could” to inform the public, citing the same brief public meeting that the county supervisor has criticized.

“Community members have not had any real opportunity to voice concerns they have with a very invasive tracking system,” ACLU spokesman Will Matthews told the paper. “This underscores why we need a process in place so that everyone has an opportunity to get answers.”

If the proposal is approved, the Santa Clara county sheriff’s department would join at least nine other local police departments in California that use Stingrays. Various agencies around San Jose, Oakland, Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego and elsewhere obtained the devices in recent years, with arrest records indicating that police are using the surveillance to make arrests for relatively low-level offenses in at least two of those jurisdictions.

It was in Florida, though, where the legal ramifications of the secrecy around Stingray use were made clear recently. Tallahassee prosecutors charged a man named Tadrae McKenzie with robbery with a deadly weapon after using a Stingray to obtain evidence against him. In a surprise decision, though, the presiding judge ordered the state to provide defense attorneys and the court with an explanation of how the Stingray actually works.

Prosecutors refused and in doing so backed away from their request to sentence McKenzie with four years in prison. They instead offered a plea deal for second months’ probation if he pleaded guilty to a second-degree misdemeanor.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.