Sixth Mass Extinction Coming? Over 30% Of All Vertebrate Species Have Declining Populations, Study Finds

The disappearance of entire species is not the only factor that contributes to mass extinction, it is also the reduction of populations within species, a new study argues, and calls the current rate of loss of terrestrial vertebrate populations a prelude to the sixth mass extinction.

The study by Gerardo Ceballos, from Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in Mexico City, and Paul R. Ehrlich and Rodolfo Dirzo, from Stanford University, looked at about half of all known terrestrial vertebrate species — 27,600 birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians. From within those, the researchers looked at detailed data of 177 mammals that have been well-studied between 1990 and 2015.

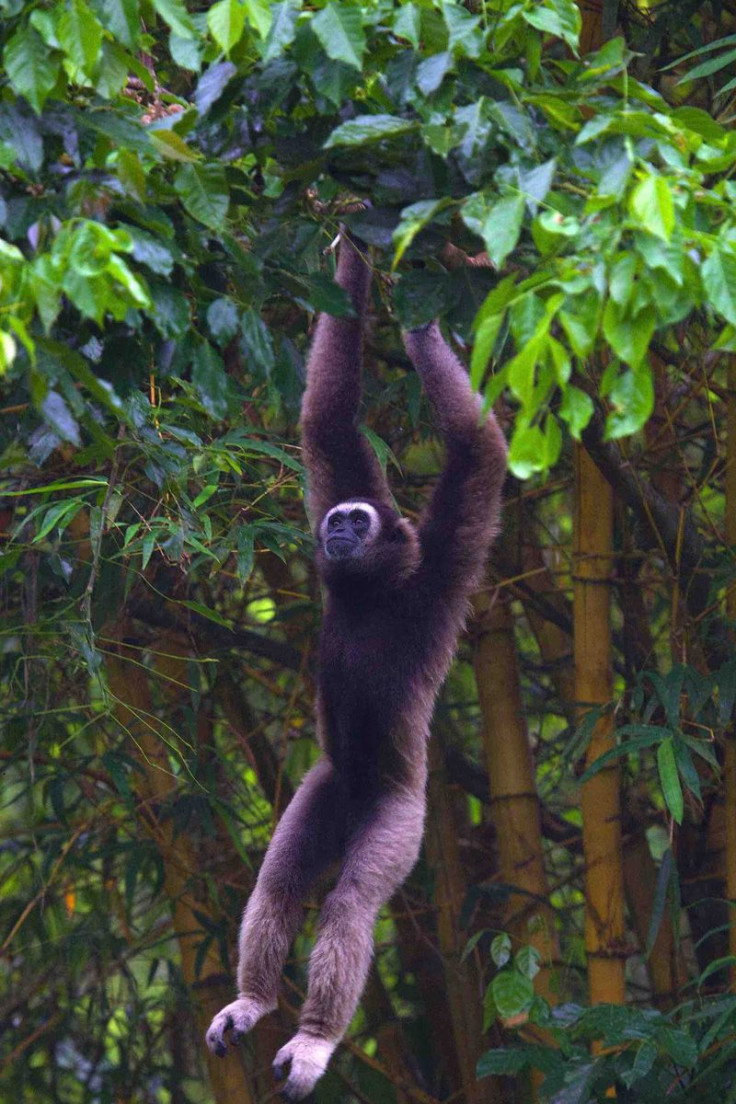

Read: 60% Of Primates, Closest Human Relatives, Could Be Extinct In 25 Years

“Using range reduction as a proxy for population loss, the study finds 32 percent of vertebrate species are declining in population size and range. Of the 177 mammals for which the researchers had detailed data, all have lost 30 percent or more of their geographic ranges and more than 40 percent have lost more than 80 percent of their ranges,” a statement on the Stanford site said.

“This is the case of a biological annihilation occurring globally, even if the species these populations belong to are still present somewhere on Earth,” Dirzo said in the statement.

Ehrlich had been part of another study in 2015 that “showed that Earth has entered an era of mass extinction unparalleled since the dinosaurs died out 66 million years ago.” Further, according to data maintained by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, about 41 percent of all amphibian species and 26 percent of all mammals were threatened by extinction, as of March 2016.

The new study, titled “Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines,” seems to substantiate those fears. Much of the blame is ascribed to anthropogenic causes which lead to large scale depletion of habitat for a number of the affected species. The areas worst affected are south and southeast Asia, where all the large mammals have lost over 80 percent of their geographical ranges.

“Anthropogenic population extinctions amount to a massive erosion of the greatest biological diversity in the history of Earth and that population losses and declines are especially important, because it is populations of organisms that primarily supply the ecosystem services so critical to humanity at local and regional levels,” the study says.

Read: First Mass Extinction 450 Million Years Ago Likely Caused By Volcano Eruption

The study’s lead author Ceballos said in the statement: “The massive loss of populations and species reflects our lack of empathy to all the wild species that have been our companions since our origins. It is a prelude to the disappearance of many more species and the decline of natural systems that make civilization possible.”

Giving examples of the importance of animals in any healthy ecosystem and even to humans, such as the pollination of crops by honeybees, Ehrlich said in the statement: “Sadly, our descendants will also have to do without the aesthetic pleasures and sources of imagination provided by our only known living counterparts in the universe.”

The authors cite human overpopulation and overconsumption in their study as the primary reasons driving the loss of individual members of various species, as well as the loss of species (two vertebrate species go extinct every year, on average), and call to undo “the fiction that perpetual growth can occur on a finite planet.”

“We emphasize that the sixth mass extinction is already here and the window for effective action is very short, probably two or three decades at most. All signs point to ever more powerful assaults on biodiversity in the next two decades, painting a dismal picture of the future of life, including human life,” the authors conclude.

The study appears in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.