Stingray-Like Cellphone Surveillance Technology Comes Under Scrutiny In California

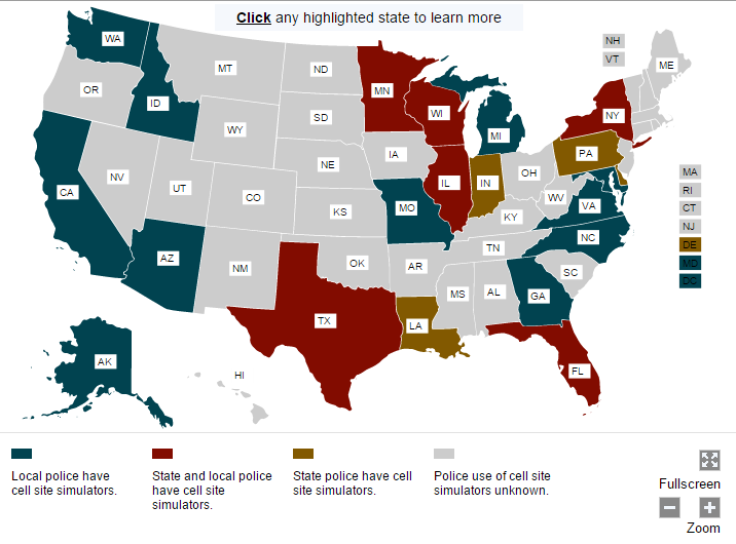

Across the U.S., police routinely track people’s cell phones -- frequently without warrants -- using controversial Stingray-like surveillance devices, which owe their generic name to the Stingray marketed by Harris Corp. in Melbourne, Florida. The American Civil Liberties Union recently found that at least 54 American law-enforcement agencies have purchased such devices in the past few years. However, the ACLU indicated the number may be higher because "many agencies continue to shroud their purchase and use of stingrays in secrecy."

Accordingly, defense attorneys are often left in the dark about how police are using the surveillance technology against their clients.

Now, a group of public defenders in California's Sacramento County are demanding more transparency around police use of the cell phone snooping technology.

In a motion filed Thursday, the public defenders called the use of stingrays "secret, intrusive and warrantless." They added that many of their clients may have been "unlawfully arrested and locked away as a result of stingray use," the Sacramento Bee reported.

At issue is whether police obtained proper warrants to use the devices. Stingrays employ a complex technology, but they basically mimic cell phone towers when intercepting calls, text messages or any other data that’s transmitted by phones in a given area. Police say the devices are used to prevent crime, but privacy advocates and public defenders say they amount to nothing more than warrantless searches.

After all, if police can simply switch on the devices and begin listening in on people’s calls, it’s easy to see how they could be misused.

The U.S. Justice Department announced Sept. 3 a new policy that would require federal law-enforcement agents to obtain warrants before using the trackers, and to inform judges on how when they plan to be used. "This new policy ensures our protocols for this technology are consistent, well-managed and respectful of individuals' privacy and civil liberties," Deputy Attorney General Sally Quillian Yates said in a statement.

Notably, the new policy does not apply to state and local law-enforcement agencies, leaving police to decide when and how the devices are used. In Sacramento, the $400,000 devices were purchased by the police in 2006. But since then, they have provided no transparency about their usage, according to the public defenders there.

"Since 2006, our office has handled over 200,000 cases. We have no idea if stingray was used in these cases," Steven Garrett, a supervising assistant public defender in Sacramento, told the Sacramento Bee. "We want [the district attorney] to ask if particular clients in these cases have had stingrays used."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.