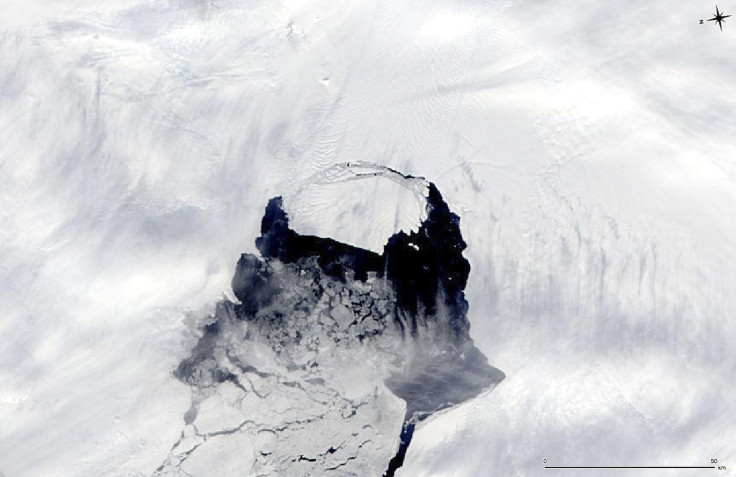

Study Links La Niña To Glacial Melt Trends As Far South As Antarctica; Finds Melting Of Pine Island Glacier In West Antarctica Slowed Between 2010-2012

A team of scientists at the British Antarctic Survey, or BAS, and other institutions have discovered that a slowdown in the thinning of Pine Island Glacier in West Antarctica could be attributed to La Ninã weather events, which are characterized by unusually cold ocean temperatures in the eastern equatorial Pacific.

The scientists said in a study published in Science that the melting of the ice shelf, into which the glacier flows, decreased by 50 percent between 2010 and 2012, likely due to a La Niña weather event. The scientists also observed large fluctuations in ocean heat in Pine Island Bay, suggesting that the ice-melting process in the region is more closely linked to changes in climate and ocean temperatures than previously thought.

“We found ocean melting of the glacier was the lowest ever recorded, and less than half of that observed in 2010,” Pierre Dutrieux of BAS and the study’s lead author said in a statement. “This enormous, and unexpected, variability contradicts the widespread view that a simple and steady ocean warming in the region is eroding the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. These results demonstrate that the sea-level contribution of the ice sheet is influenced by climatic variability over a wide range of time scales.”

Scientists know that much of the thinning of glaciers is due to a deep oceanic inflow of Circumpolar Deep Water, or CDW, the water mass in the Pacific and Indian oceans that can be warmer by up to two degree Celsius. This warmer water then makes its way into a cavity beneath the ice shelf melting it from below.

In 2009, a higher CDW volume and temperature in Pine Island Bay led to an increase in ice-shelf melting compared to the last recorded measurements in 1994. Successive observations made in 2012, and mentioned in the current study, showed that ocean melting of the glacier was the lowest ever recorded during the period.

In addition, the top of the thermocline, which is the layer separating cold surface water and warm deep waters, was found to be about 250 meters deeper compared with any other year for which measurements are available.

According to the scientists, the lowered thermocline reduces the amount of heat flowing over the underwater ridge that blocks the deepest ocean waters from reaching the thickest ice. So its presence enhances the ice shelf's sensitivity to climate variability as any changes in the thermocline can alter the amount of heat filtering through.

Scientists said that the fluctuations in temperature recorded by them could be explained by particular climatic conditions. In January 2012, the dramatic cooling of the ocean around the glacier is believed to be due to an increase in easterly winds caused by a strong La Niña event in the tropical Pacific Ocean.

La Niña is an ocean-atmosphere phenomenon, which has the opposite effect to El Niña. During a La Niña event, sea surface temperatures in the tropics tend to be lower, according to scientists.

“These new insights suggest that the recent history of ice shelf melting and thinning has been much more variable than hitherto suspected and susceptible to climate variability driven from the tropics,” Adrian Jenkins of BAS and the study’s co-author said in the statement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.