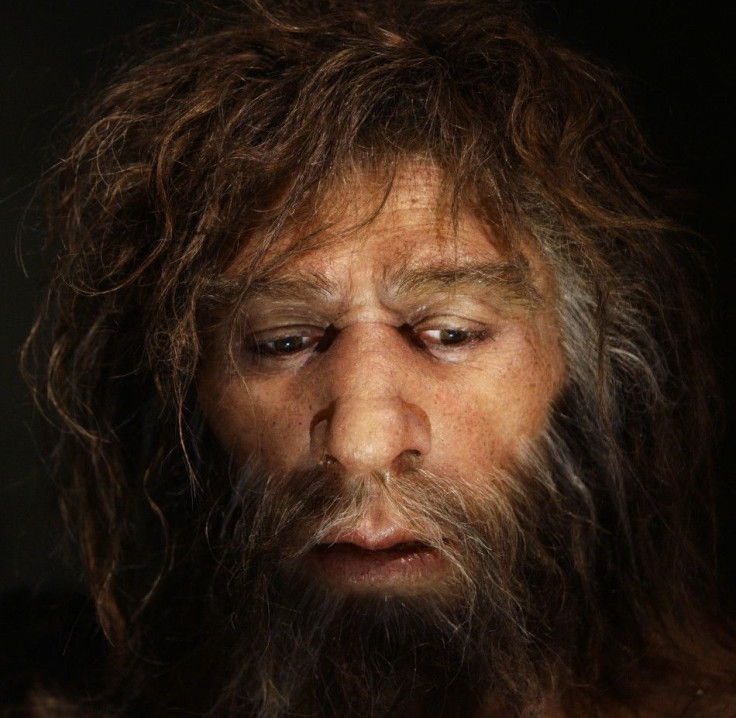

Superior Numbers Allowed Humans to Outlast Neanderthals: Study

Theories for how humans outlasted Neanderthals, our ancient rivals, have ranged from brain capacity to climate conditions, but a new theory posits something more simple: there were more of us.

Neanderthals had flourished in Europe for hundreds of thousands of years before disappearing about 30,000 years ago. A new study published in the journal Science found that humans outnumbered Neanderthals by about 10 to one in a region of Southwestern France, and its authors believe that a massive influx of humans migrating from Europe overwhelmed Neanderthals in the competition for resources.

"Numerical supremacy alone may have been a critical factor" in humans surviving, the study's authors wrote.

After studying ragments of stone tools and animal food remains in France's Perigord region, Paul Mellars and Jennifer C. French of Cambridge University concluded that humans far outnumbered their Neanderthal counterparts. There was also evidence that humans had superior hunting techniques and better social ties with other communities of humans.

"It was clearly this range of new technological and behavioural innovations which allowed the modern human populations to invade and survive in much larger population numbers than those of the preceding Neanderthals across the whole of the European continent," Mellars said.

"Faced with this kind of competition, the Neanderthals seem to have retreated initially into more marginal and less attractive regions of the continent and eventually -- within a space of at most a few thousand years -- for their populations to have declined to extinction -- perhaps accelerated further by sudden climatic deterioration across the continent around 40,000 years ago."

Joao Zilhao, a research professor at the University of Barcelona, said that the study was too simplistic, arguing that "the overwhelming genetic and paleontological evidence shows what happened was assimilation, not replacement." His statement seems to be supported by a recent study finding that most humans are genetic descendants of Neanderthals, which suggests that humans and Neanderthals mated with one another.

Neanderthals were thought to have created symbolic objects such as jewelry and to have formulated language, making them the closest known thing to humans. Considerable debate remains as to whether they are subsets of the same species or if they are distinct.

The human/Neanderthal dichotomy was overturned in December of 2010, when a team of researchers discovered fossil evidence of a third humanoid species, dubbed the "Denisovans," that roamed Asia and may be the ancient forefathers of people in Papau New Guinea.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.