Supermassive Black Hole's Jets Regulate Rate Of Star Birth In Galaxies

The universe is home to countless galaxies more massive than the Milky Way, which should, in theory, be bursting with star formation, but they aren't -- an observation that goes against most current models of the universe and star formation. Why do these galaxies, despite having an extremely high gas density, not have a correspondingly high rate of star birth?

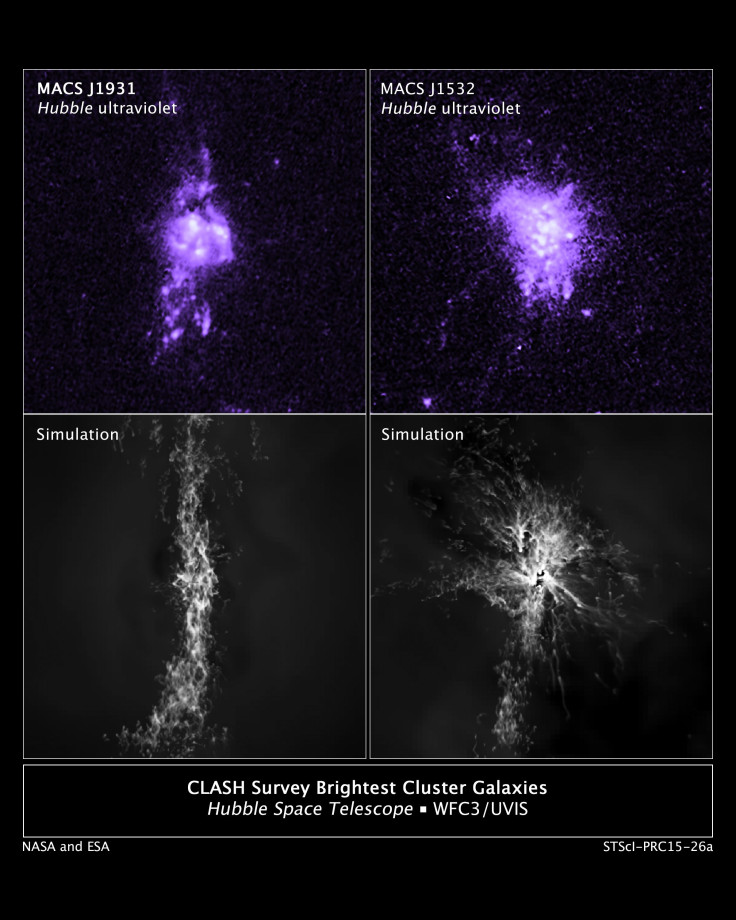

Observations made using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and a host of other space- and ground-based telescopes might have finally answered the longstanding question. Additionally, they have also uncovered a unique process that allows some of the cosmos’ largest galaxies to continue producing stars way past their prime.

The latest findings, gathered by two independent teams and explained in two separate studies conducted by Michigan State University and Yale University, show that high-energy jets shooting from the black hole at the center of a galaxy play a crucial role in the self-regulating cycle that controls the rate of star formation. The researchers found that these jets heat a halo of surrounding gas, which, in turn, regulates the rate at which the gas cools and falls into the galaxy.

“Think of the gas surrounding a galaxy as an atmosphere,” Megan Donahue of Michigan State University, the lead author of one of the studies detailing the findings, said, in a statement Thursday. “That atmosphere can contain material in different states, just like our own atmosphere has gas, clouds, and rain. As the jets propel gas outward from the center of the galaxy, some of that gas cools and precipitates into cold clumps that fall back toward the galaxy’s center like raindrops.”

These “raindrops” eventually cool down enough to transform into star-forming clouds of cold molecular gas that end up making “a swirling ‘puddle’ of star-forming gas around the central black hole.” The heat generated by the black hole then heats up the gas again and pushes it outward to restart the whole process.

“The entire cycle is a self-regulating feedback mechanism, like the thermostat on a house’s heating and cooling system, because the ‘puddle’ of gas around the black hole provides the fuel that powers the jets,” NASA said in the statement. “If too much cooling happens, the jets become more powerful and add more heat. And if the jets add too much heat, they reduce their fuel supply and eventually weaken.”

This cycle of heating and cooling could be the main reason behind the “arrested development” seen in many massive elliptical galaxies that have lower-than-expected stellar birth rate. In these galaxies, stars continue to develop along the jets of active black holes, albeit at a moderate rate.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.