Supply And Demand: European Smugglers Are The Winners As New Routes Open Up For Refugees Fleeing Conflict In The Middle East

FOT, Hungary -- Ahmed Amir, 15, sat on his bed desperately trying to access Wifi networks on his phone so he could talk to his brother in Germany. Amir had not wanted to end up here, in an overcrowded home for refugee children traveling alone, in a small town 14 miles outside of Budapest. The Afghan teenager was on a mission -- along with hundreds of thousands of other desperate people fleeing war and conflict -- to get to northern Europe, but Hungarian authorities had caught him trying to cross illegally into the country from Serbia. For Amir, there was only one way to get out of the home and back on the road: hire a smuggler.

Smuggling is big business in the world of refugees. Over the last 15 years, migrants and refugees have paid traffickers over 16 billion euros to reach Europe, according to the Migrants’ Files, a data journalism organization. In 2015 alone, about 630,000 refugees have entered the European Union illegally, the chief of Frontex said Monday. This year alone, Europol, the law enforcement body that works to encourage collaboration between Europe's police departments, has registered 29,000 people that it suspects of helping to smuggle refugees into Europe.

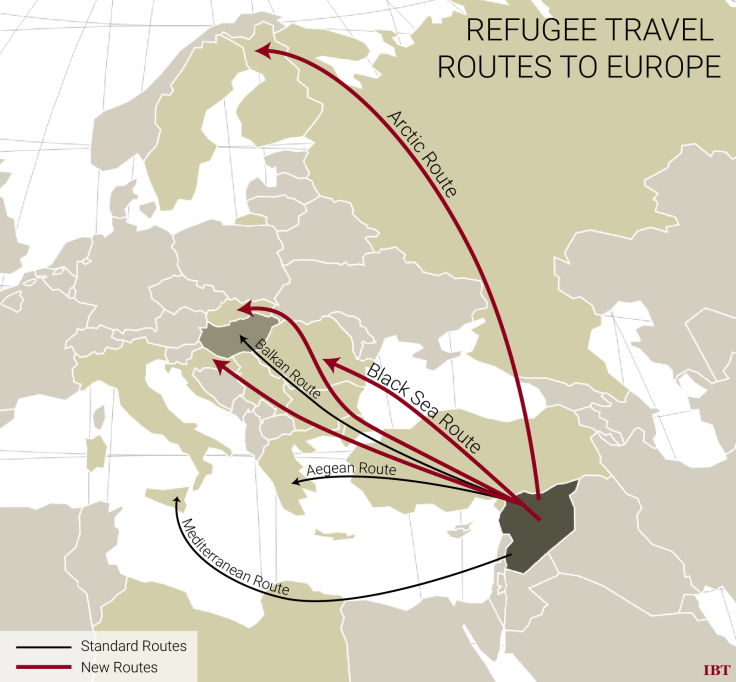

As refugees respond to tightening border controls in Hungary and Serbia, smugglers are taking advantage of new channels that are opening up, charging large sums of money to transport people across European borders illegally. According to refugees interviewed by IBT in Germany and Hungary, smugglers can expect to earn up to $15,000 per car trip, driving refugees across eastern Europe and into more accommodating countries like Germany, Holland and Sweden.

The money is tempting; one smuggling trip can provide the kind of earnings that will cover the rent for a family apartment in Budapest for almost four years. This illegal work is particularly appetizing given the high unemployment rates in Hungary, Serbia and Croatia. In Serbia and Croatia, the unemployment rates are 20 percent and 17.5 percent respectively. In Hungary, the unemployment rate began to fall in May when the refugee crisis exploded, but a considerable gap remains between the richest and the poorest: the top 20 percent of the population earns close to five times as much as the bottom 20 percent.

Extensive smuggling networks already exist to take refugees from countries such as Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan to eastern Europe. The cost is anywhere from $2,000 to $8,000 depending on where the refugees are smuggled from and the route they take. Once in eastern Europe it costs about an additional $1,000 to $2,000 to be smuggled into Germany. Since many trains have stopped running from eastern Europe to Germany, smuggling is the only option for many.

Amir is among their number. “I don’t want to stay [in Hungary]. I want to go to Germany to go to school and my family, my brother, is also there,”Amir told IBT.

Amir made the journey from Afghanistan with the help of a smuggler. He was traveling with his brothers but, somewhere along the way, he said, they were separated and he tried to make it to Germany on his own.

“I came through the trees from Serbia to Hungary,” he said, showing his mosquito bites from the journey.

He walked from Croatia, to Serbia, but when he tried to cross into Hungary through one of the illegal border crossings, the police caught him and transferred him to a home for unaccompanied minors.

Hungarian authorities who catch refugees are legally required to collect their fingerprints and file them in a European database. Those refugees are then officially processed for asylum status in Hungary. And if the refugees are processed in Hungary, it means other countries can turn them back under the terms of the European Union's Dublin Regulation, which states that refugees can only claim asylum in the first EU member state they enter.

To counter these rules, refugees are paying smugglers to get out of Hungary and using different names upon arrival in northern Europe.

Smugglers are not hard to find in Budapest. They wait -- some in small groups, some individuals -- outside the city's main train station. They stand back from the main entrance and watch the refugees pour into the main building to line up for trains out of the city. From afar, they pick the refugees they think they can get to commit and pay for a ride to a different country, usually by truck. Most of the people that are smuggled from eastern European countries are young, single men.

Ali, a Syrian interviewed by IBT in Munich, Germany, hired a smuggler in two separate places in Hungary. First, he hired a smuggler to cross Serbia's border into Hungary and on to Budapest. Once in Budapest, he paid a smuggler to take him to Germany.

"There are so many smugglers just standing at Keleti train station," Ali said. "It is so easy. They just come up to you and ask if you need one. Ours took us by car to Munich."

Undocumented refugees or migrants often have to pay more for smugglers, Ali said, because it is riskier for the smuggler. Smuggling rates also vary depending on the refugee's wealth and country of origin. Families traveling with a lot of people from the Middle East often pay more than a boy traveling alone from Afghanistan. Traveling by car and truck costs more than being escorted by a smuggler on foot. Sea crossings are the most expensive of all; smugglers charge around $1,200 per person for a place in a rubber dinghy from Turkey to the Greek island of Lesbos.

As eastern European countries continue to close their borders, smuggling prices are increasing. Hungary's decision to build a wall on its southern border to stop the flow of refugees and limit the number of trains heading to Munich and Vienna, Austria has smugglers rubbing their hands in glee.

It's simple market economics: borders close, demand increases, and so does the price. But it's a price most refugees are willing to pay, when the potential returns -- safety, security, economic opportunity -- are so good.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.