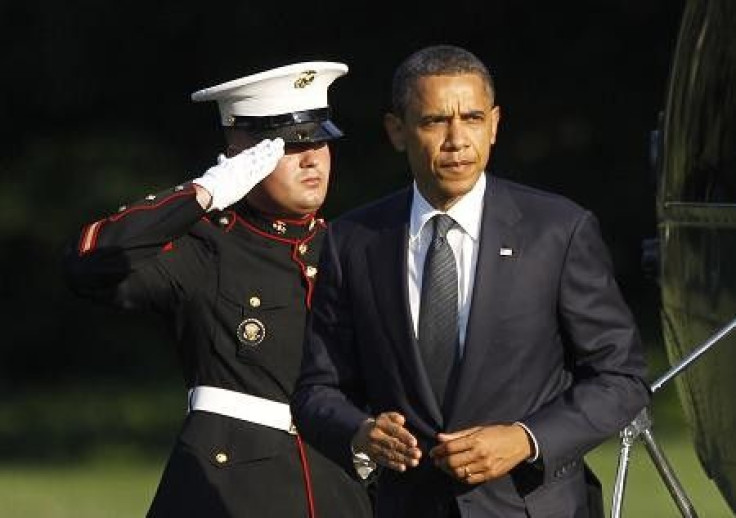

Syria News: Has Obama Talked Himself Into A Corner On Intervention In Syria?

One way to interpret President Barack Obama’s surprise decision in late August to seek congressional approval for a military strike in Syria is that the president was looking for a way out of getting involved in the war-torn nation. After all, if it’s politically dangerous to bomb Syria without first asking Congress, it’s exponentially worse to do so after Congress votes it down.

Even though Syrian President Bashar Assad is believed to have crossed Obama’s red line by using chemical weapons against his own people, the strike would be largely unprecedented. As a New York Times report details Monday, the impending strike does not conform to any previously set avenues or criteria used for attacking another nation, be it self-defense, to prevent a humanitarian crisis, or with the backing of the international community or an international body like the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). But if the administration wants to be let off the hook, it isn’t acting like it.

Instead, President Obama could be walking into just that trap of his own making -- pushing the case for intervention so forcefully that even if Congress doesn’t buy it, and the United Nation's Security Council predictably does not back it, he will have no choice but to strike anyway.

The president is using all the tools at his disposal to convince lawmakers and the public, both of which are skeptical of getting involved in the Syrian conflict, to get behind a limited campaign against Assad. Obama will sit for a series of television interviews Monday with six major broadcast and cable networks to make his case before addressing the nation directly from the Oval Office Tuesday night -- a very rare move for the president. U.N. Ambassador Samantha Power argued for intervention at the liberal Center for American Progress on Friday and National Security Adviser Susan Rice will do so at the New America Foundation on Monday.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry testified before Congress twice last week, arguing that the safety of Americans, American troops and civilians of other countries are all at stake. Syria’s use of chemical weapons “concerns every American’s security,” Kerry said in France over the weekend. If the U.S. doesn’t respond to the use of chemical weapons, he said, then bad actors will feel emboldened to use chemical weapons and everyone will be in danger.

As Obama and his top aides forcefully make the case for intervention, the administration has not held back in characterizing the Assad’s alleged use of chemical weapons as a threat to American security and a human rights violation, citing both as reasons to strike Assad and degrade his chemical weapons capabilities. Further, if the threat is that grave, then how could they simply accept a no vote from Congress or the U.N. Security Council and do nothing without looking weak, or worse, look like they were exaggerating the threat to begin with.

This is especially true since the administration has made the case that it does not need Congress’ approval to strike Assad. That means it will be much harder for the administration to essentially throw up its hands and say, "we wanted to strike but Congress wouldn’t let us." By arguing that Congress’ vote is more of a suggestion than a command, the administration has set up a situation where declining to strike -- and in its own words placing Americans’ in danger of future chemical weapons attacks -- will be the administration’s choice.

What's more, although the Obama administration has one more way out by claiming that it doesn’t have the authority to attack without the approval of the U.N. or the backing of an international coalition, it seems to be closing that escape hatch, too. During an interview on NPR Monday morning, Ambassador Power didn’t respond to repeated questions on the legality of a strike under international law, but pointed to past situations in which it has been “structurally impossible” to go through the process of getting U.N. approval.

White House counsel Kathryn Ruemmler went further than Powers to specifically make the case that Obama would not be violating international law if he ordered a strike without a green light from the U.N. In an interview with the New York Times, Ruemmler said that though the Syria situation “may not fit under a traditionally recognized legal basis under international law,” the unique situation in Syria would make action “justified and legitimate under international law.” Although the administration has argued to Congress that Americans will ultimately be put at risk without action, legally, the question at issue is whether one sovereign nation can attack another in order to enforce a humanitarian convention against the use of chemical weapons when the safety of U.S. citizens is not directly being threatened. Relying heavily on the humanitarian argument can lead to a slippery slope that would loosen the international restrictions on attacks between nations.

In a way, the administration had no choice but to go all out in its campaign to win over Congress. After all, why would lawmakers put their own jobs on the line to vote for a military strike the administration itself wasn’t fighting hard for or making a strong case for. Still, the administration’s claims that it has the authority to attack without Congress or the U.N. put it in a politically problematic spot if it comes out of this week with support from neither and a substantial record of arguing that Americans’ security is at stake.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.